Diving in Antique? Beware of ‘garaban’

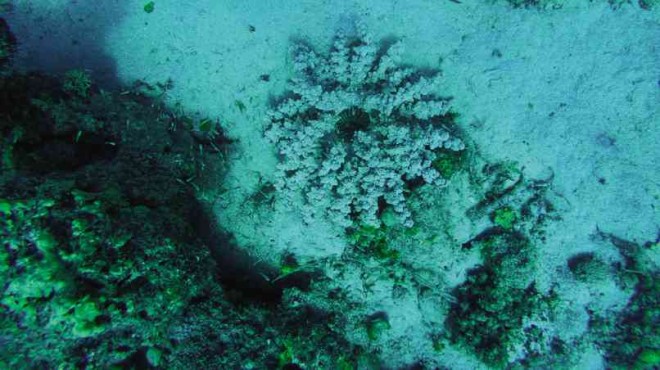

HELL’S fire sea anemone, locally called “garaban,” is endemic to the waters of the Indo-Pacific. FLORD NICSON CALAWAG/INQUIRER VISAYAS

CULASI, Antique—The water was inviting, so the three children on Batbatan Island in Culasi, Antique province, decided to dive and swim in a nearby coral reef.

“I accidentally stepped on something and I felt a very burning sensation,” 7-year-old Inday (not her real name) said in Kiniray-a language. “I shouted so loudly because it was very painful.”

Her friends rushed to her aid and brought her home, as she was grimacing in pain from a big wound in her left foot.

“Right after seeing the wound, we knew at the very instant that my daughter touched the garaban,” said the girl’s mother, Jac, who later arrived from another village. Jac washed and cleaned the wound, and applied some antiseptic.

The garaban, or hell’s fire sea anemone (Actinodendron plumosum), is endemic to the seas of the Indo-Pacific, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific, a biogeographic region comprising the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and those connecting them in Indonesia.

Article continues after this advertisement“Most sea anemone species are harmless to humans, but the garaban is highly venomous and its sting can cause severe skin ulcers,” said professor Gilma T. Tayo of the University of the Philippines Visayas’ Division of Biological Sciences.

Article continues after this advertisementThe garaban can grow only up to a foot, Tayo said. “It is unknown how long they live. In fact, this species can be hundreds of years old in the wild and, in captivity, has been known to last 80 years or more.”

It is not among the endangered species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, but much attention is needed to protect and conserve the species.

Cultural practice

Allan Macuja, barangay chair of nearby Malalison Island, has been warning tourists about the garaban’s presence when they want to dive in the waters off the islands, specifically Batbatan and Maniguin. “We always remind them not to touch any soft corals or sea anemones, especially the garaban,” he said.

“When we go fishing and free diving, we always make sure not to touch any garaban in the wild,” said his brother, Jelson. “Because of our father’s advice, we also pass this information to our children and our fellow fishermen so that they will be careful in dealing with the toxic marine organism.”

Macuja recalled his grandparents as telling them to be extra careful in going to places and drinking anything, or “we might be a victim of kilkig,” known in Karay-a culture since time immemorial as the practice of poisoning. The lethal concoction is prepared by sun-drying a branch of the garaban, grilling it under fire and powdering it.

Only a few know the real source of the poison, however.

One fisherman from Batbatan narrated seeing his cow one afternoon after grazing in an open field. “The cow was acting unpredictably. It was running, making a loud noise and rolling down. In just a few hours, it died,” he said.

“When we opened its stomach, all we saw were burned intestines and internal organs,” the fisherman said, surmising that the animal was a victim of kilkig.

Like soft coral

The hell’s fire sea anemone can be light yellowish green, tan, brown, light green or gray—monochromatic or a combination of colors—with leaf-shaped, feathery tentacles of varying sizes. From a distance, it looks like a soft coral or a Kenya tree coral.

Depending on its appearance and distribution, the species is also known as hexacoral, fire anemone, pinnate anemone, sand anemone, knobby-tentacled anemone, beaded-tentacled anemone, tree anemone or branching anemone.

The garaban are found at depths of 3-20 meters. They live singly in sandy and rubble-covered bottoms on coral reefs, burrowed deep into the substrate with all but their tentacles showing. When disturbed, they can retract their entire body into the sand and be virtually invisible.

Marine biologists have listed the hell’s fire sea anemone as among the world’s toxic and stinging sea creatures, along with the sea wasp box jellyfish, Irukandji jellyfish, Portuguese man o’war, cannonball jellyfish, moon jellyfish, lion’s mane jellyfish, crown-of-thorns sea star, textile cone, reef stonefish, banded sea krait, short-tail stingray, soft sea slugs or nudibranchs, lionfish, puffer fish, scorpionfish, Caribbean fire coral, blue-ringed octopus, stargazer fish, striped eel catfish and sea nettle.

Ecological importance

“Generally, sea anemones are ecologically important members of tropical coral reefs,” said Cyndy Sol Rodrigo, technical assistant of the Biodiversity Partnership Program of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources in Western Visayas.

“They serve as symbiotic hosts to several species of fish, such as clown fish, invertebrates and shrimps, some of which control parasite loads on larger reef fish, yet little quantitative information is available on their biology,” Rodrigo said.

However, no clown fish are naturally associated with this type of sea anemone, though some Periclimenes shrimps are found with it. Studies of fish benefiting from the sea anemone are not well-known.

“Anemones, like their coral cousins, establish symbiotic relationships with green algae. In exchange for providing the algae safe harbor and exposure to sunlight, the anemone receives oxygen and sugar, the byproducts of the algae’s photosynthesis,” the National Geographic explained on its website.

Bio-prospecting

According to Dr. Christopher Warlowe A. Caipang of Temasek Polytechnic’s School of Applied Science in Singapore, the hell’s fire sea anemone is related to corals and jellyfish, and “uses venom-laden tentacles to stab passing victims with a paralyzing neurotoxin—rendering them helpless.”

“Since this species contains a powerful neurotoxin, there is a big potential for this species for bio-prospecting. As a matter of fact, marine organisms have developed some very powerful and specialized chemicals that are now used in medicine as well as having other uses for humans.” Caipang said in an online interview.

Bio-prospecting is the search for plant and animal species from which medicinal drugs and other commercially valuable compounds can be obtained. Since the venoms in marine species are far more powerful than those in terrestrial organisms, most of the species are subjects of bio-prospecting.

Mayor Joel Lumogdang said the municipality was “already crafting specific ordinances to protect and conserve the garaban and other valuable species that have potential for bio-prospecting. In this way, we can make sure that everything is regulated.”

“We are aware that the garaban thrive off the three islands of Culasi, that is why we always make sure that no one is extracting this species in the wild,” said John Sumanting, municipal information and tourism officer.