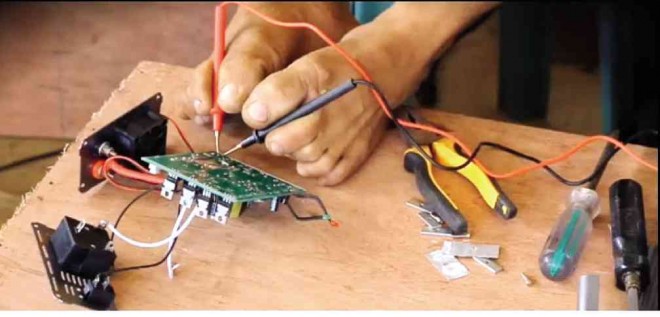

EXTRAORDINARY FEAT Using his feet, armless Marjo Lardera (right) has proven himself adept at fixing broken gadgets and appliances, his interest in consumer electronics honed further by his training under the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority, or Tesda. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

People call him “gubaniko,” a combination of the Filipino word “mekaniko” (mechanic) and the Ilonggo word “guba” (destroy).

It’s a nickname that Marjo Lardera has gotten used to, as the childhood moniker referred to his fondness for taking apart electronic gadgets and small household appliances to find out how they work.

Born without arms, Lardera recalled how he had once dissected a perfectly functioning radio using his feet in their home in Concepcion, Iloilo province, but was unable to put it back together. It earned him a scolding from his mother, Ester, but it did not discourage him from fiddling—this time, secretly—with other gadgets and home appliances, including a wall clock.

“I was really curious to see how they function. It was amazing for me to discover how they work,” said this youngest in a brood of 10.

Barangay’s go-to person

Lardera is one of a number of persons with disabilities (PWDs) who have been certified in various fields by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (Tesda). He is licensed to service consumer electronics after finishing in 2010 the 360-hour course at Professional Electronics Institute Inc. in Iloilo City.

The 29-year-old father of one is now a far cry from the “gubaniko” of his childhood, having become the go-to person in his barangay (village) for appliances that need fixing.

But the journey toward earning the trust and confidence of his customers wasn’t smooth, he said of those early days when he was training and the first few years after he received his license.

Lardera recalled how one of his trainers tried to discourage him from pursuing the course, not because he lacked confidence in the PWD’s capabilities, but because he was afraid Lardera could hurt himself in the process.

“[But] I stood by my dream of finishing the course,” Lardera said. “I told him, ‘You haven’t seen yet what I can do,’” he added of his dialogue with his trainer, who has since become a good friend.

Humor for rapport

As for his customers, Lardera recounted how some of them were afraid that their appliances could get damaged further, “because I was using my feet to fix them.” He tried humor to allay those fears. “I would crack jokes to build rapport. I would tell them I’d use the two fingers protruding from my right arm if they can pick up the tools using their feet.”

The strategy proved to be effective, because the shop he co-manages in Concepcion Poblacion with his friend, Leopoldo del Castillo, is flourishing. Castillo thought of opening the shop in 2013 after he had seen Lardera’s determination to do well while he was still working in his older sister’s electronic shop in Sara, Iloilo.

While Lardera was born armless, he said he didn’t want to consider himself disabled.

“I can do most of what normal people can do,” he said. “[But] I have also grown to accept discrimination. As a way to fight it, I don’t mind what people say about me. Instead, I show them what I can do.”

Lardera added: “If you let what other people are saying about you get into your head, you’d really lose hope. It will ruin you.”

No poster boy for PWDs

Like many of us, Lardera admitted to questioning God about his purpose in this world. It was through prayers and trust in himself that he had managed to overcome his self-doubt, he said. Now he makes full use of his skills, fixing not only small appliances but making solar lamps as well.

But though what he can do—including carpentry and loading and firing a gun—may be considered remarkable by most, Lardera said he didn’t want to be a poster boy for persons with disabilities.

“[People] shouldn’t look at me as a model. They should do what they can. Because if they look at what I can do, they might lose confidence in themselves,” he said.

Able-bodied beggars

What keeps him going, said Lardera, is his dream of securing a better future for his wife, who helps him out in the shop, and his 2-year-old son. He doesn’t want to end up begging on the streets, like some able-bodied people whom he finds “insulting.”

“They would rather beg than use their bodies to find a decent job,” he explained.

Given the chance, Lardera said he was willing to work abroad to ensure a steady income for his family and to earn enough capital to start his own electronic shop that would also sell electrical supplies, which are in short supply in the province.

Bringing back a broken gadget or appliance to life brings him joy and fulfillment, Lardera said.

“I feel fulfilled and happy whenever I do that,” he added.

RELATED STORIES

Persons with disabilities get jobs building chairs for GenSan schools

Aquino: Gov’t will make sure persons with disabilities are treated right