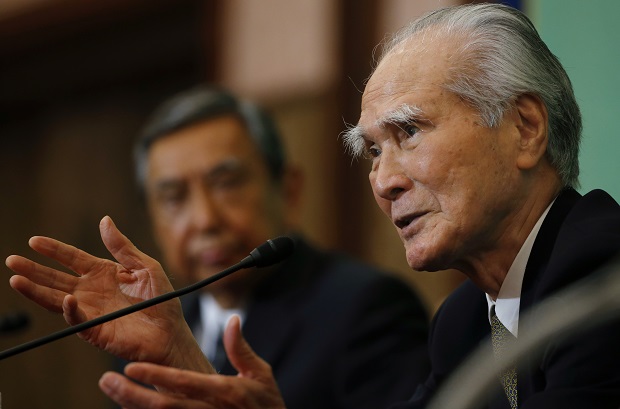

Japan’s former Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama, right, speaks as former Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono listens during a press conference at the Japan National Press Club in Tokyo Tuesday, June 9, 2015. The two former Japanese political leaders known for their key apologies over Japans World War II aggression said Tuesday that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe should not water down their words. Murayama, who authored Japans landmark 1995 apology marking the 50th anniversary of the wars end, demanded that Abe honestly spell out the countrys wartime actions to address growing international concern that he may revise history. AP

TOKYO, Japan — Foreign ministers from Japan and South Korea are holding a rare meeting Sunday on the eve of the 50th anniversary since their countries normalized relations marred by Japan’s colonization and World War II conquest.

Yet, the ties between the most important U.S. allies in Asia are so low that one hoped-for outcome of the meeting is an agreement for the countries’ leaders to just show up at Monday’s ceremonies in their respective capitals, instead of exchanging written statements.

“It’s a grave situation, and what’s more serious is that Japan’s diplomacy toward South Korea has turned harsher against the backdrop of public sentiment,” said Junya Nishino, a political science professor at Keio University.

According to a poll by Japanese newspaper Asahi and South Korea’s Dong-a Ilbo, published Saturday, more than half of the respondents in both countries say their image of the other side has worsened in the past five years.

The poll also found that 87 percent of South Koreans feel strongly about better relations with their neighbor, compared to 64 percent in Japan.

“Trust between Japan and South Korea has been largely lost, and it’s not easy to restore it right away,” said Nishino.

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and South Korean President Park Geun-hye have yet to hold fully fledged bilateral talks since taking office in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Washington has been concerned about its allies’ strained relations.

They are rooted in Japan’s colonization of Korea, from 1910 to the end of World War II. The relations improved in the late 1990s, following Japanese apologies, cultural exchanges and a Korean pop culture boom in the 2000s, but nosedived a few years ago largely because of differences over their shared history.

Many Koreans still remember Japan’s 35-year colonization as the era of brutality and humiliation, during which they were forced to use Japanese names and language while their pride, heritage and sense of identity were severely threatened. After normalizing ties, it took three more decades before Seoul officially allowed Japanese films and other popular culture back into the country.

The latest downturn started in 2012, when then-South Korean President Lee Myung-bak visited a cluster of Seoul-controlled islets also claimed by Japan.

As public sentiment soured, ethnic Koreans in Japan, many of whom descendants of forced laborers, became target of racial insults by right-wing extremists.

Anti-Korean books and magazines have become bookstore staples, while Korean pop idols who once dominated Japanese TV shows have largely disappeared, and many shops in downtown Tokyo once known as Korea Town closed down.

Nishino said the deterioration in relations could also be traced to South Korea’s rising economic clout and international profile that has touched the nerve of many Japanese, who have lost confidence in their own leadership amid economic slump and political disarray.

Yun Byung-se’s visit Sunday will be the first by a South Korean foreign minister since 2011. He will hold talks with his Japanese counterpart, Fumio Kishida, then meet with Abe on Monday before attending anniversary events in Tokyo.

The ministers are expected to discuss Japan’s sexual enslavement of Korean women and other outstanding issues related to wartime history.

Tokyo maintains that the 1965 treaty settled all compensation claims between Japan and South Korea, but Seoul says wartime crimes, including sexual slavery, that were not largely unexplored when the agreement was signed should be readdressed.

Economic relations are still generally strong, although Japanese tourist arrivals and direct investment in South Korea have declined since 2012, while those from South Korea have remained relatively stable.