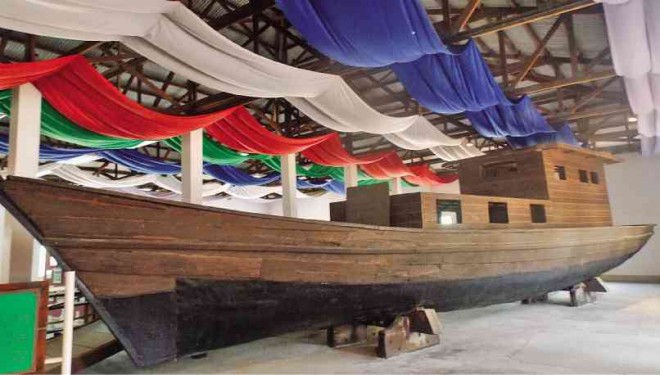

THIS BOAT, displayed at the former Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Morong, Bataan, took refugees fleeing Vietnam to the Philippines in the 1980s. ALLAN MACATUNO

ALMOST 34 years ago, a group of 12 Vietnamese men and women sailed into the high seas for over a week after leaving Nha Trang City in the southern part of war-torn Vietnam. On the morning of June 14, 1981, they were seen and rescued by Filipino fishermen after “drifting aimlessly” off Napot Point in Morong, Bataan.

Their boat was said to have been first mistaken for a piece of floating debris and that all its passengers were too weak to stand, having been without food and water for days.

On May 12, 1981, two motorized fishing boats carrying 65 Vietnamese, 11 of them children, left the same city and headed for the open seas. While at sea, these “boat people” met huge waves described to be “more powerful than the boats they were built to withstand.”

Six days later, they reached the shore of Mabayo Beach in Morong and were rescued by members of the Philippine Constabulary-Integrated National Police (the predecessor of the Philippine National Police), Mabayo officials and residents.

Such stories of “boat people” are depicted in several markers that now serve as a reminder of the Indochinese refugees that Bataan hosted from 1980 to 1994.

These markers are displayed in a museum inside the Bataan Technology Park Inc. (BTPI), which used to be the site of the Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC).

Daisy Fernando, a former worker at the refugee camp and who was involved in the social services program for refugees, says the museum houses some artifacts and photographs that tell stories and hold memories from the camp.

Ideal community

“The refugee camp here was an ideal community. All the needs of the Indochinese refugees were provided and their stay here was life-changing,” Fernando says.

Since the Philippines was able to help the Indochinese refugees in the past, she says the government could still replicate what it did during the time of PRPC, especially now that the Rohingya people from Myanmar and Bangladesh are fleeing persecution and seeking countries that would accept them.

“I believe we have an obligation to help the boat people. We have once proven that we could help transform their lives and we can use that experience to do it again,” Fernando says.

While inside the 365-hectare PRPC, whose operation was funded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the lives of refugees were transformed through various trainings and services they received, she says.

“The refugees underwent language and skills trainings. They were also taught how to engage themselves in community services,” she says.

Temporary home

The PRPC was the temporary home to some 400,000 Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians whose documents were processed at the camp from 1980 to 1994 prior to their resettlement to countries like the United States, Canada and Norway.

“I had a great experience working with the refugees. I did job placement interviews and the language barrier didn’t hinder us from doing our work,” Fernando says.

The refugees were taught conversational English and were trained to be “service-

oriented” while inside the camp.

“Everyone was doing his or her part, whether you are a refugee, volunteer, social worker or teacher. There was no idle time in the camp,” Fernando says.

Refugees, who lived in bunkhouses,

received complete social services since the camp was equipped with clinics, hospitals, schools, markets, a gasoline station, churches and religious temples.

‘Monkey house’

“We even had a social rehabilitation center here that served as a jail for troublemakers. The Vietnamese called it a ‘monkey house’ because they said people who were into ‘monkey business’ were jailed there,” Fernando says.

After the last wave of Indochinese refugees left the camp in 1994, they left behind a few artifacts and structures that serve as a

reminder of their community, says Clemente Zaragoza Jr., a tour guide at the former PRPC.

Zaragoza says tall grasses and shades of trees inside the camp hide some of the religious remnants of the PRPC, which include shrines, temples and monuments.

A tour around this former refugee camp allows a visitor to see some of the religious relics and places of worship. Zaragoza says the PRPC has preserved a Buddhist temple, replicas of the Bayon shrine and Laos’ Pha That Luang monument, and a religious Khmer shrine.

All bunkhouses used by the PRPC refugees had been demolished because these were already dilapidated, he says.

This former refugee camp underwent a facelift under the Bases Conversion and

Development Authority (BCDA) in the mid-1990s and was converted into what is now BTPI, an industrial, commercial and tourism enclave.

The former PRPC site, Zaragoza says, is being groomed as a “histo-cultural” destination and could also serve as a venue for leisure, sports, picnics, corporate training, retreat and spiritual pilgrimage.

In spite of the place’s transformation, Fernando says she and other former PRPC workers are working together to preserve the artifacts and monuments associated with the Indochinese refugees.

“While I can still vividly remember some stories about the refugee camp, I make sure that I document them through collecting relics and pictures from other former PRPC workers,” Fernando says.