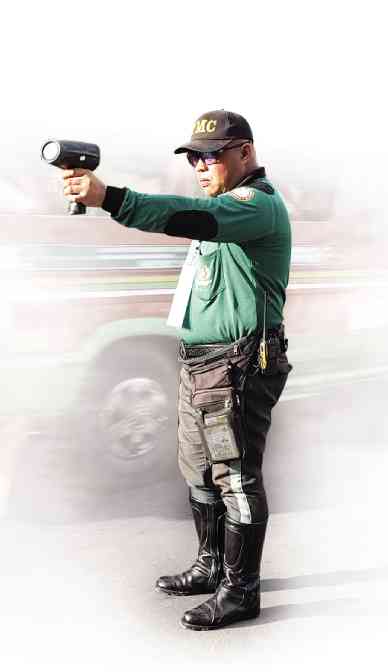

An officer from the Davao City Traffic Management Center trains his speed gun on vehicles. KARLOS MANLUPIG

Speeding, overtaking and racing—the usual triggers of potentially fatal road rage in Metro Manila and other urban centers with a highly mobile populace—are now rarely seen on the streets of Davao City after its tough-talking mayor, Rodrigo Duterte, issued Executive Order No. 39.

The order, implemented since the first quarter of 2014, imposes speed limits on all kinds of motor vehicles, from 60 kilometers per hour to as slow as 30 kph in the downtown areas. So far, 10,183 drivers have been arrested for speeding, according to Traffic Management Center chief Rodelio Poliquit.

“A bike can run faster,” says Noel Panay, a jeepney driver, who finds the rule absurd. Commuters feel the slow pace of travel is acceptable, though, if in return, it saves lives.

EO 39 sets speed limits for vehicles “within the territorial jurisdiction of Davao City,” but exempts legitimate emergency cases, such as those involving ambulances and law enforcement agencies. A total of 136,283 vehicles have so far been registered in the city, government records show.

Duterte has maintained that the issuance of the order is timely as it applies the brakes on fast driving, which contributed to the sharp increase in the number of vehicular accidents in Davao City over the past years. He cites a road accident in September 2010, in which two people were killed and 16 others were injured. Most of the victims were students.

New speed limits

A dramatic 41-percent drop in vehicular accidents has been reported from last quarter last year, when the executive order was implemented, Poliquit says. From 7,000 cases from January to September in 2013, the number went down to 4,000 for the same period in 2014, he says.

The 60-kph limit is for vehicles coming from Sirawan in Toril District to Ulas Crossing, Lasang to Panacan in the north, Calinan to Ulas, and C.P. Garcia Highway-McArthur Highway to Panacan.

Vehicles must slow down to 40 kph from Ulas to Generoso Bridge/Bolton Bridge in Bangkerohan, Panacan Crossing to J.P. Laurel Avenue-Alcantara, and Ma-a Road Diversion to McArthur Highway.

Within the city proper, the limit is 30 kph.

Longer travel time

While the executive order has indeed slowed down the occurrence of road accidents, jeepney and taxi drivers are not moved by its impact. Instead, they are disappointed that their profits have screeched as well. Along with commuters, they complain that travel time is now twice as long.

Panay says he and other jeepney drivers can make only four round trips in their routes instead of the usual five. His net earnings of P1,000 daily have been cut in half and so has his P6,000 weekly net income.

“We can’t run fast to pick up more passengers,” he says.

For taxi driver Rey (not his real name), who has four children and struggles to put food on the family table, his average daily income of P450 has fallen substantially because he can no longer speed up to pick up more passengers.

“Sometimes I earn only P200. How will we be able to meet our needs, especially when the cost of living is very high? I can’t do anything about it, I can only work hard,” he says.

Compounding his situation is the recent government reduction of the flag-down rate by P10 for taxis.

Adjusted travel routine

Rey sees the speed limit as the bigger culprit and feels helpless. “If I go against the law, I will not be able to afford to retrieve my driver’s license,” he explains.

Mass communication student Aivy Villarba believes EO 39 should still be implemented though it took her a while to get used to the new routine of leaving home an hour earlier than usual.

“Mayor Duterte’s aim was public welfare over welfare of other sectors,” Villarba says. “Also, there are no car racers anymore at midnight because if they race, they will get caught.”

Gwena Caubang says the speed limit is “a great way to discipline drivers, especially in a populous place like Davao City.”

“It decreases the rate of accidents, and hit-and-run incidents, especially along the highways,” Caubang says.

She wishes the road rule will also be enforced in her hometown in Baganga, Davao Oriental province, where, she says, many drivers are reckless.

Private car owners

For private car owners Steely Caballero and Prince Canda, the slow pace of travel in the city is “a hassle” and that they prefer the minimum speed in downtown areas be upped to 40 kph.

Manila-based entrepreneur Moje Ramos-Aquino recounts her experience in coming to Davao. It took her an hour and a half to travel 6 kilometers.

“I’ll go back to Davao when they lift the speed limit. In the meantime, I will bring my business and my money somewhere else,” she says.

But Poliquit says business shouldn’t be based on the speed by which vehicles can travel in certain areas.

“It will be more inconvenient if people are not safe to walk on the road, such as the elderly, the children who are going to school and the pedestrians. If people are not safe here, then who will invest?” he says.

Social media strategist Reymond Pepito thinks that even if EO 39 is unappealing to some, the majority finds it important.

“Others may say that it affects their business transactions, but I feel like the implementation of speed limits is not a problem,” Pepito says. “Road-widening and well-functioning traffic lights can address the issue of congested roads and traffic in the city. One should not compromise safety.”

“I live in Tagum City where roads are less busy, but I still wish for us to have our own vehicular speed policy to avoid road accidents,” he says.