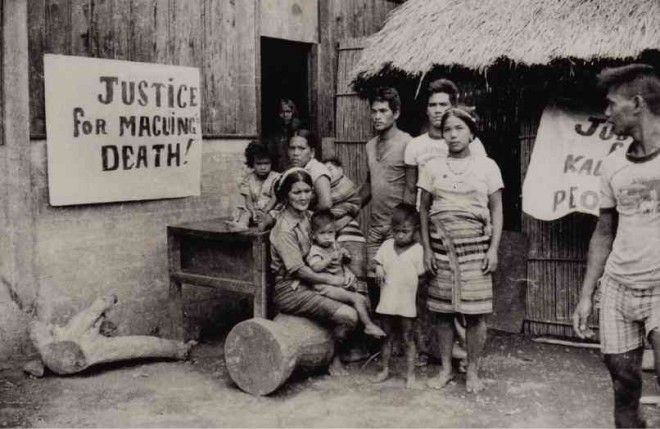

SAMUN, (seated, with child on lap), wife of Macli-ing Dulag, and her children put up streamers in their house in the village of Bugnay in Tinglayan to call for justice over the murder of the Kalinga elder. MA. CERES DOYO

MACLI-ING Dulag, a pangat (village elder) from the community of Bugnay in Tinglayan, Kalinga, was murdered by government soldiers 35 years ago for leading the struggle against the World Bank-funded Chico Dam project under the regime of strongman Ferdinand Marcos.

Macli-ing died on April 24, 1980 when soldiers, led by Lt. Leodegario Adalem, fired at his house and those of Pedro Dungoc, his neighbor, and another resident opposing the project.

The Chico hydroelectric dam project would have submerged the sacred lands of indigenous peoples near the Chico River—from south of Bontoc in Mountain Province to north of Tomiangan in Tabuk, Kalinga—to provide electricity for the lowlands. If not for Macli-ing’s leadership and his determination to stand up to power, whole communities would have been displaced by the project.

Every April 24 since 1985, Cordillerans mark People’s Day to honor Macli-ing. Recently, the University of the Philippines (UP) Press published the book, “Macli-ing Dulag: Kalinga Chief, Defender of the Cordillera,” by Inquirer columnist Ma. Ceres Doyo. The book has an accompanying anthropological text by Prof. Nestor Castro of the Department of Anthropology at UP Diliman.

The accompanying study on the Cordillera complements the story on Macli-ing in the context of the history and culture of the region, the mountainous ancestral domain of major indigenous communities in the Philippines.

‘Watershed moment’

“This book is yet another way of honoring and keeping alive the memory of the man who fought for his people, the Kalinga people, whose mountain homes were marked to give way to so-called development. Macli-ing’s struggle served as a watershed moment,” writes Doyo.

The book is an expanded version of an award-winning 1980 magazine article that led to Doyo’s interrogation and chastisement by the military. While the article put her and the magazine’s editor and publisher in trouble with authorities, the piece earned a journalism award handed by no less than Pope John Paul II during his 1981 visit to the Philippines.

Elders in Bugnay deeply remember Macli-ing but younger members of the community remain clueless on his larger contribution to the story of indigenous Filipinos.

MACLI-ING offered his life to protect the sacred lands of his people. LIN NEUMANN, ASIA NEWS SERVICE, 1980

Asked how the retelling of Macli-ing’s story could remind the Butbut-Kalinga and other Filipinos of his struggle and triumph, Doyo says: “I would tell them the impact of Macli-ing’s death not only on the people of the Cordillera but on people beyond. The elders and the youth should be proud that someone like Macli-ing once walked among them.”

“I would probably show the young the scar I have on my right elbow, narrate how difficult it was at that time to reach their village,” she says.

Doyo’s team was the first fact-finding group that reached the village after Macli-ing’s death. Several fact-finding missions, among these church-based and human rights groups, came later.

“It was difficult during that time—there was no food, water was scarce. The military was everywhere. We had to be vigilant,” says Apo Takhay, a Bugnay woman elder who is now more than 100 years old.

She recalls how a group of women dismantled and burned the campsites of project proponents in Basao, a village next to Bugnay. In one incident, she tells about the lusay—when elderly women disrobed and displayed their tattooed torsos and limbs in front of government surveyors and soldiers to protest the dam construction. This act, she says, is believed to bring extreme harm and bad luck to men observing them.

Apo Takhay says “the village mourned, but did not weep,” when Macli-ing died.

Her memory of Macli-ing is vivid: “He was eloquent and calm, full of courage. People intently listen to him with stillness.”

Doyo says Macli-ing’s words had an “almost mystical, spiritual quality.”

Asked what she wants to ask Macli-ing if she interviews him today, Doyo says: “Where did he draw his courage and timeless wisdom? Who is Kabunian to him? I would have wanted to have a really good glimpse not only of his mind but of his heart.”

Doyo says she also wants to learn about his childhood, the influences in his life, and what Bugnay and the Chico River were like before militarization and the proposed dam threatened the community.

Today, Macli-ing’s name is etched on the Wall of Remembrance of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City, one of the Filipino martyrs and heroes who offered their lives for freedom and justice during martial law.

Editor’s Note: The book, “Macli-ing Dulag: Kalinga Chief, Defender of the Cordillera,” will be launched at UP Baguio at 9:30 a.m. today to commemorate the 35th death anniversary of Macli-ing. Doyo says it was in UP Baguio where her team, “tired and bedraggled,” held a forum to report the results of their fact-finding investigation in Bugnay 35 years ago.