Bones worth keeping

THE MUSEUM features not just rare animals but bones of common house pets as well. J. CUDIS/CONTRIBUTOR

Bring the elephant to Philippine soil. This is a personal mission that American bone collector and conservation advocate Darrell Dean Blatchley has set out to do since he founded D’Bone Collector Museum in 2012 in Davao City.

It seemed to be a simple task, at first. No, he does not intend to bring a replacement for Mali, the famous yet aging elephant at the Manila Zoo.

What Blatchely plans is to transport a complete set of full-grown elephant bones from Africa, set it up for viewing and thus be able to educate Filipino children, especially those from Mindanao, about this remarkable animal. But now, not only does he need $22,000 to make that happen, Blatchley also needs to hurdle pervasive bureaucracy, rising costs of import duties and hollow promises from supposed donors. He remains undaunted though.

After recently receiving his Datu Bago Award, the highest award given by the government of Davao City to its notable constituents, Blatchley will be flying to Manila to look for 22 donors to donate at least $1,000 to the cause, arrange the transport of the bones, and finally, take the elephant to his museum. He is so sure he will get the support he needs to make it happen.

Preventing extinction

Article continues after this advertisementTwelve years back, in a hunting store in the United States where preserved rhinos, tigers and elephants were on display, a seemingly innocent encounter with a store worker made Blatchley decide to set up a museum that would allow Filipinos to learn more about natural history.

Article continues after this advertisement“He asked if my wife, who was with me at the time, was a Filipino and pointed out that Filipinos were all the same. He sounded offensive and we were fuming,” Blatchley narrates, noting that this comment had been a turning point for him. Filipinos, that store worker explained, looked so awed and ignorant when they see preserved large animals, unlike other Asians. “Why?” the store worker asked Mary Gay Blatchley. “Don’t you have these kinds of places in your country? How do you learn about natural history then?”

Bugged with the question, the Blatchley couple went back to the Philippines and visited the National Museum. There they saw the shameful truth: The Philippines gives little value to educating its people about natural history by preserving animal artifacts.

“It was on the third floor, in a small, old room with a leaky ceiling—the Philippines’ collection of bones and artifacts. I had [bigger] collection of bones in my living room,” he quips.

Blatchley maintains that there is a need to educate Filipinos about what the Philippines is blessed with, learn about the animals in other countries to get them to think about conservation. He laments that the future generation, his children, will never ever see a live western black rhino and hopes that by letting them see at least the bones of these animals, it will lead to better appreciation of the need to conserve them and their habitat, and prevent their extinction.

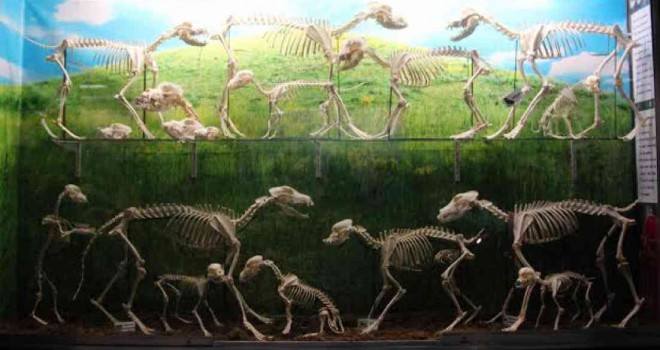

Fast-forward to the present, Blatchley, with support from his missionary parents, his wife and friends from around the world, has expanded his private collection from 350 to over 1,000 species that are now displayed in well-lit glass cases in a three-floor building. The bone collection includes that of a 12.5-meter (41-foot) sperm whale, a 9-m (30-foot) python, a megamouth shark, several crocodiles, a large collection of preserved rare insects as well as different species of house pets.

“All I want is to not be asked by my own children why I let those animals become extinct,” Blatchley says.

In the Philippines, according to studies, animals become extinct even before they are discovered and documented due to environmental degradation. World Animal Foundation lists the Philippines as one of the islands in the world suffering extreme habitat destruction, along with New Zealand, Madagascar and Japan.

A crocodile tooth will usually fall off and a new one quickly grows. This basic knowledge has driven many enterprising Filipinos to breed crocodiles instead of the traditional practice of killing them for their teeth and skin. J. CUDIS/CONTRIBUTOR

Changing mindsets

But how can the Philippines learn to appreciate the value of preserving the remains of dead animals if it falters in respecting the living animals?

Terralingua (www.terralingua.org), an organization dedicated to biocultural diversity conservation, has pointed out the connection between the loss of indigenous peoples’ traditions and understanding of the species, including ancestral beliefs, to animal extinction.

For example, the Philippine crocodile used to thrive in the northern Sierra Madre because the native Agta fishers were knowledgeable about the behavior and ecology of the crocodile and its habitat. Agta beliefs and practices also included strong taboos against killing and eating crocodiles. With the disappearance of Agta culture and the lack of knowledge about the animal, the Philippine freshwater crocodile is now critically endangered.

For Blatchley, Filipinos need to readopt the indigenous mindset about respecting nature and everything in it. D’Bone Collector Museum is a reminder of the world’s rich biodiversity and the sad fact that it is slowly destroyed by humans.

The museum has been a way to educate not only children but adults as well on why respecting animals, dead or alive, is important.

Economies of conservation

“In Thailand, when an animal dies, they recover the bones and put it in their house. It’s not a fascination of the animal dead. It’s a fascination of when the animal was alive,” Blatchley notes.

“If a carabao, which has given bountiful crops and good life for a Thai family dies, they preserve and hang its horns in the house to remember it. Filipinos chop it off, make it into a soup, or burn and destroy it,” he adds.

In many cases, locals who find dead whales, dolphins, even those rare sea creatures that are found awash on the shores will chop these into pieces, sell or eat them and bury what remains. Blatchley says promoting awareness against this practice has been a constant challenge but asserts he is winning it.

“Now people call me or come to me to report about a sea creature that had been awash on the beach. I come and help rescue it if it is still alive, or take it to the museum and preserve the bones if it is dead.”

These undertakings are done by the museum in closer coordination with the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources more than the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

Blatchley says the government needs to review its framework to animal conservation. For example, the law states that when an eagle bred in captivity is released, the government closes off 100 or more hectares of land that in turn endangers the livelihood of the people in the area. People then resort to killing other animals for livelihood or even to killing the eagle to make the government reopen the area for people.

Blatchley also highlights the success of conserving Philippine freshwater crocodiles as a result of legalizing the skin industry of saltwater crocodiles.