(Last of two parts)

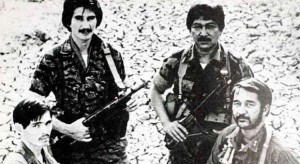

RAM boys Gringo Honasan, Eduardo Kapunan, Rey Rivera and Tito Legaspi PHOTO FROM “Breakaway: The Inside Story of the Four-Day Revolution in the Philippines”

MANILA, Philippines–In the excerpts from the book “Endless Journey: A Memoir,” published in the Inquirer, Jose Almonte sought to underline his role (to fill what he regarded as gaps in the planning) as the Reform the Armed Forces Movement’s link to the civilian opposition.

“We needed credible civilian leaders to get their support,” he asserts. “We needed Cory Aquino and Jaime Cardinal Sin.” Almonte mentions Peping Cojuangco as finally having arranged a meeting with Cory Aquino at her Times Street residence sometime in February “as the demonstrations against Marcos intensified.”

Had that meeting taken place only between Peping Cojuangco, Joe Almonte and Cory Aquino, our objections might have been less forceful, or maybe even absent altogether. But for some reason, Almonte brings into the picture three RAM stalwarts, none of whom, after reading his account, had the slightest idea what he was talking about and in such a lengthy narrative.

In the first place, the RAM had already incorporated into its plans, efforts to meet up with opposition leaders in the civilian sector. (They were not exactly babes in the woods who needed help from the likes of Almonte.) Members of the core group had met with Cardinal Sin in late 1985 followed by a past-midnight rendezvous with Cory Aquino in the first week of December 1985 (not February 1986 as claimed in the book) at the residence of the late Commodore Carlos Albert at the Philamlife Village in Quezon City (not on Times Street and not in Cory’s kitchen). Cory Aquino did not want to meet at her residence, which was not secure. We met at the dining room of the Albert residence.

Cory had just returned that evening from her first provincial sortie in Batangas and was complaining of a sore shoulder, apparently from being virtually mauled by her overeager supporters. Honasan (whom Almonte did not include in his bogus February meeting) offered female security for Aquino, and she acquiesced. Needless to say, if Aquino met with Almonte after this meeting, we would have known from the reports of the security elements we provided her. We received no such reports.

We told Aquino we would not necessarily vote for her, but would certainly help to ensure the conduct of clean and honest elections. Reacting like a seasoned politician’s wife, she regaled us with stories about common folk offering support for Ninoy Aquino, not in terms of money but in the form of farm produce, such as eggs and fruits. She opined in her soft-spoken manner that Marcos had already “a lot of money and supporters” so that she would appreciate every little help from the military and from the RAM.

Later, in a trip to Singapore in January 1986, she delivered a speech where she revealed she had a secret group within the military that supported her, apparently alluding to the RAM. When we were queried by the international and local press regarding her remark, we remained tight-lipped. After all, it was a private matter that we were bound to protect.

Meeting with Biazon

Before the meeting with Cory Aquino, members of the core group spent a few days in Davao City. We came to know that one of the plans of the Aquino group was to declare a separate government in Davao supported by the Philippine Marines contingent in that province led by then Col. Rodolfo Biazon. We spent a couple of nights with Biazon discussing the political situation, where the good colonel presented meticulously prepared diagrams depicting in full color the dynamics of social groups relevant at the time and the perceived role of the military in the entire scheme of things. We never mentioned our plans to Biazon.

Kamalayan ’86, a campaign for clean and honest elections, was our cover. Biazon likewise did not disclose what we thought we knew about the plans of the Aquino group in that province. But we understood each other. We simply suggested that when push comes to shove, Cory Aquino was better situated in Manila, near the center of the action, instead of being in faraway Davao.

Also in January (before Almonte got around to it), we already had several meetings with Peping Cojuangco and Ramon Mitra. We told the pair that the RAM was prepared to move against Marcos and that when that happens, Cory Aquino should better be in Manila.

Meet with Cardinal Sin

The meeting with Jaime Cardinal Sin, on the other hand, took place in late September 1985 in the Archbishop’s residence. A number of priests were also present to receive our core group. Aloud and in the presence of his priests, Cardinal Sin spoke to us about military discipline and the need to adhere to the rule of law. But as we filed out of the meeting room, he embraced us individually, imploring each one of us not to make the exercise “too bloody.”

In his Feb. 22, 2015, article in the weekly magazine of a newspaper, Robles wrote:

“The days following the assassination at the tarmac, the atmosphere at the defense ministry where I was assigned was lethargic. I and many others in the department no longer felt like working, the whole idea of having a government seemed pointless.

“In the two years following the tarmac incident, the idea for reform within the AFP (Armed Forces) took shape. Troops were inadequately equipped. Rotation policies were not properly implemented. The upper echelons were clogged up because certain retired generals were extended. Some were even recalled to active service. At the same time, selected officers were promoted ahead, sometimes way ahead, of qualified ones already due. Demoralization in the officers’ corps affected the fighting capability and discipline in the lower ranks.

“The need for internal reform in the Armed Forces was developed and propagated by a group of young officers. By mid-1984 they were putting out flyers, mimeographed bulletins and other printed materials to spread the gospel of reform. Seen from today’s perspective, their work would seem weak and ineffectual since everything had to be done manually, without the benefit of computers, scanners and printers. No Internet.”

Labor, peasant groups, etc.

Surprisingly, their seemingly rudimentary efforts met with vibrant if muted response. And there was something else. The reform idea resonated among many other sectors of society. Such that a year later, the RAM found itself deep in meetings with labor and peasant groups, city workers, church groups, media stalwarts, business executives, schoolteachers even. The consensus was: Marcos must go. By any and all means. Even Armed Forces attachés of neighboring countries voiced similar sentiments. A ranking officer from Singapore was summarily recalled for being outspoken on the need to oust Marcos.

It was like being swept by a slow but steady and strong undertow. The reform movement within the Armed Forces unexpectedly found a wider support base among the populace, and was inexorably drifting from the outwardly safe concept of peaceful reform to the decidedly dangerous prospect of direct power intervention.

As may be gleaned from the above narrative, Almonte’s idea of providing a link to the civilian population in February 1986 comes rather late in the game. It is highly simplistic, ignores nuances and consequently underestimates the RAM’s well-grounded grasp of political events. An accomplished theoretician, Almonte oddly fails to do justice to the profound and far-reaching concept of reform espoused by the RAM. He confined his view to the intervention aspect since being a newcomer he did not see or understand the reform part, which served as the solid foundation of the movement.

In his desire to claim a vital role in the RAM’s planned intervention, he portrays the group as a naive conglomeration of coup plotters who sorely needed his sage advice and persuasive talents. But in the end, his gravest mistake was not so much to inadvertently underestimate the power of reform, as to willfully invent narratives that exclusively portray him in a favorable light. And if these were not enough, to dare flaunt his flights of fancy and endeavor to pass them off as gospel truth.

Backtracking

Almonte himself later backtracked from the bold assertion that Honasan plotted to kill Marcos, and that he was instrumental in dissuading Honasan from doing so. He now claims in recent TV interviews that the plan was only one of the several options considered, an obvious concession on his part, after Honasan’s earlier sharp reaction, to wit: “You don’t have to lie or invent things to sell a book.”

Indeed in planning for a forcible overthrow, the RAM carefully considered a wide range of options, from the benign to the drastic. The specter of violence constantly hovered over their drawing board, as it were. (As a retired soldier, Almonte should have readily recognized this.) But certainly, forcible methods did not dominate their design. For instance, at one point, many hours were devoted to figuring out how to protect the children in the Palace in case the RAM achieved intrusion into Malacañang.

Honasan asserts that the purported efforts of Almonte to discourage him from killing Marcos are a pure concoction.

Small but notable

There are other small but nonetheless notable items. The quarters of Almonte could not have been a “jump-off point” for the RAM because the tactical group assigned to storm Malacañang had their own assembly point. Neither could there have been a command center at Villamor Airbase run by Vic Batac and Almonte “to coordinate the movement of all the forces,” because there already was an existing, pretested command center for the assault group elsewhere in the city. But even this the RAM command center did not coordinate the movement of “all the forces,” a function falsely claimed by Almonte.

They gathered at Almonte’s quarters at his last-minute behest. Turingan avers that they were completely surprised by the announcement by Enrile and Ramos on TV withdrawing support from Marcos. Turingan’s instinct was to immediately join the Enrile-Ramos group at Camp Aguinaldo. Almonte’s reaction, and that of Gen. Rodolfo Canieso (who was with them at the time), was to choose to stay behind because, according to them, moving to Aguinaldo would mean certain slaughter.

So Turingan proceeded without Almonte and Canieso to join the group in Aguinaldo. So much, therefore, for that purported phone call from Batac to Almonte informing him earlier of the planned announcement to withdraw support.

Egotistical assertions

As for Almonte then rushing over to Aguinaldo with Turingan, as claimed in his book, what happened was Turingan left and Almonte stayed behind, only to join the main body very much later.

The point of this refutation, as it were, is not only that Almonte constantly fabricates stories, but also that he apparently did not expect anyone in the RAM to dare question his version of events. For too long, the RAM has tolerated his self-flattery. But now Honasan is challenging Almonte to produce even just one witness to validate his egotistical assertions.

(Editor’s Note: The authors, core founding members of the Reform the Armed Forces Movement [RAM], told the Inquirer that the above article “is based entirely on a three-part series highlighting the excerpts from Jose Almonte’s book, ‘Endless Journey: A Memoir.’

“We have not read the entire work. Other instances of untruthfulness, in other portions of his memoir, are not within our concern to ferret out. However, the examples given are sufficient to convince us that Almonte has published a dishonest and irresponsible book.”)

FIRST PART

Almonte’s memoirs: ‘Endless concoctions’