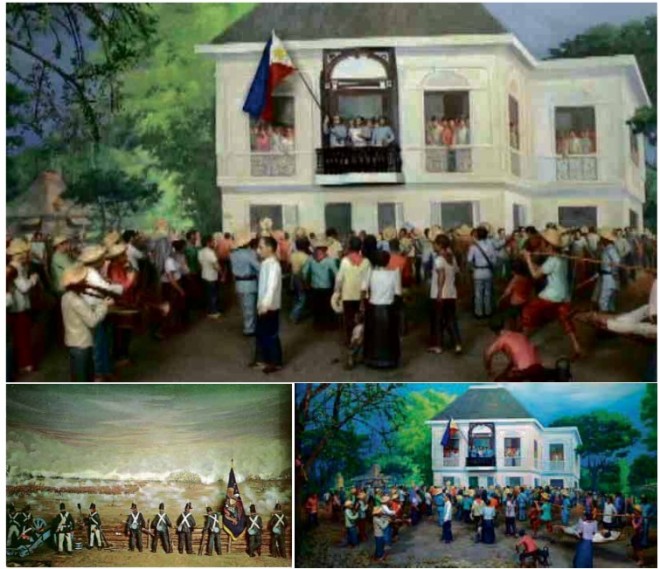

IN PAPIER-MÂCHÉ dioramas of hand-sized figures, combatants, victims, correspondents, witnesses, weapons of war in battlegrounds lighted up, shadowed, or blacked out, each scene, beveled to the wall and framed in glass

The legend was passed on to us, the post-World War II young generation who felt trapped, we joked, in the heat or leaking roofs of the United States Army Officers’ leftover Quonset huts in the Diliman pasture lands in the campus of the University of the Philippines in Quezon City.

Bowed over by ennui, while mumbling through Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace.”

The legend was that a World War II nuclear bombing pilot, in his first year of peace, turned Trappist monk of the Order that takes on vows of Perpetual Silence.

So he dreamt of a miniature museum where he was to be the curator-director, letting in white-wimpled and black-robed nuns herding their wide-eyed girls and boys through his virtual, seemingly Toy Land.

Where, letting them go afterwards, he hoped that never would they scream for a Superman sword or a noisy rat-tat-tat toy machine gun.

And those aged, one-eyed, limping veterans of any wars would vomit all the horrors of wars that they had suffered for one lifetime.

By the erasing powers of Dementia, he had hoped to confer on these museum visitors a state of grace in losses of all memories.

He was going to be innocently, inadvertently a God-Director in his own Universe.

“War and Peace” is a dream scene from the film script “The God-Director” by Virginia R. Moreno. It won the first prize of P150,000 in the Don Pablo Roman competition organized by the Social Security System. Its publication now is in memory of the late Benedictine friar Gabriel Casal, who imagined Ayala Museum’s Dioramas of War for Peace. It is also timely as the country marks the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Manila.

I choose the universe, and kept all other worlds out. And here in my painted heavens are swung electric constellations, my own suns and moons, stars and eclipses, nights and days, self-powered galaxies of illuminations, shadows, sunsets to sunrises, dawn to star falls, boxed-in.

These light up, and darken, at my will, autonomous of natural sunlight and unnatural nights.

In this black box, all warmth and light must be controlled, or life within them will crumble and rot in the raw heat, blistered by the raw light.

Climate of seasons, winds and tides, rise and fall, come and go at the fingertip of my voice.

I propose an inverted sky to my artists, so inverted it is, and suggest brushing the clouds violet shy and winging across it a calligraphy of birds—these tranquil paintings above a still-smoking battlefield the eyeless soldiers see, before they were stopped from seeing.

Many roofs of peace, unique, over earth’s convulsed floors of war! And terrain reversible—rain, black thunder and lightning over the dry white still bones of the war dead.

Such ineffable powers I lay claim to, from out of a worktable, where each day artisans cut up figures and landscapes of war, whittle stones for bones, wrap flash paper around sculptures of wire, to make one soldier, raise a regiment of soldiers—all the same, before they are costumed, most animals when naked—so capped, booted, clothed, armed, what chilling powers one can summon by just painting soldiers’ uniforms primitive red against black, water-coloring winter skins paler against Afrique black, barefoot against nailed boots, a hatchet knife alive against the dull iron mouth of a machine gun.

From flat cartoon drawings, they swell to men of substance, of texture and stances, waiting to kill to kill to kill and not to be killed, again and again … still a tableau of war that one can visit, return to, check for change.

They do not change, they must not be changed. All else outside go into paroxysms of life. The dioramas are still, are perfect.

The guides disturb the perfection by hurrying the malingerers, who drink long and intensely of each scene, but she cuts off their thirst not by slaking, but by diverting them frivolously to another or the next one over there. Everything is the same to her.

I must impress on her lessons on leisurely, regal distinctions.

A caption writer sometimes makes mistakes, mixing up enemies with allies, friends with traitors, assassins for the assassinated.

Does it really matter? It is only a word, displayed. He believes men do not even read, do not care. There are real wars for them!

But I know the error, it

exists, since he who enters here becomes the soldier he called from the dead. What chaos, what poignancy to slip into an enemy’s hand, into the enemy’s finger that pulls the gun’s trigger at oneself.

I dream in turn of the perfect viewer. I enter into their glass cages, one heartbeat of life between me and their paper hearts, my tear-filled eyes looking in are the same pitying eyes looking out, at me, at my closed, artificial life, my skin of paper, my bones of wire, my painted silent mouth, deaf, without death.

High Priestess of Poetry Virginia Moreno is highly regarded for her works in literature, theater and cinema.