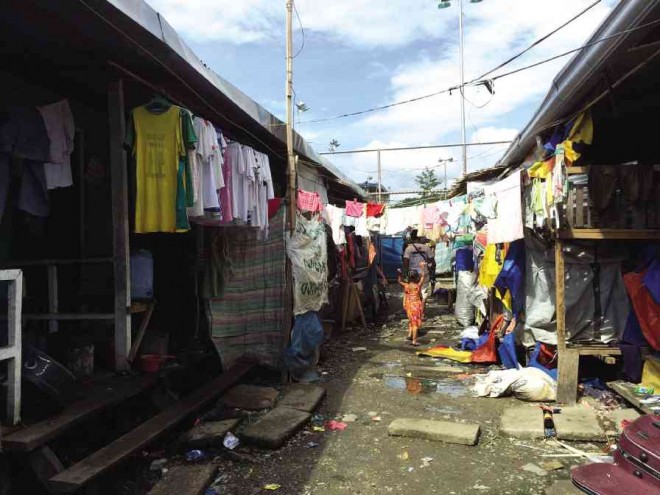

BUNKHOUSES, now dilapidated, were built for Zamboanga City residents but have turned into breeding grounds for prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases. JULIE ALIPALA

ZAMBOANGA CITY—Four months into her pregnancy, Karina has one fervent wish on New Year’s Day: “Allow us to return to our original place. I want to raise my children with dignity.”

Karina (not her real name), a laundry woman, wants a way out of her miseries at Don Joaquin F. Enriquez Memorial Sports Complex in Zamboanga City, including being prostituted to feed her seven children and an ailing husband.

They have been staying there along with hundreds of other residents of Barangay Santa Catalina and other villages since followers of Moro leader Nur Misuari laid siege on the city on Sept. 9, 2013.

“There were so many boarding houses, so many households, where I could wash their clothes. What I earned from doing laundry was enough to feed my children. My husband was earning, too, as a carpenter there,” she told the Inquirer.

“It will be pure luck if you find a family wanting somebody to do the laundry for them here,” Karina said. She and her family occupy a cramped makeshift shelter fashioned out of an old tarp, sacks and scrap lumber at the grandstand of the sports complex.

The priority for all of the families was food, she said, stressing that “food and health assistance is waning.”

Empty stomach

“When the stomach is empty, a mother will do everything she can to provide for the family,” said Shallom Fatima Pir Allian, project director of Nisa Ul Haqq Bangsamoro, a nongovernment organization that conducted a research among internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Citing Katrina’s and other cases, Allian said “sexual abuse among men, women, gays and children in prostitution will always happen when the issue of food security is not properly addressed.”

Despite the official denials, Nisa Ul Haqq documented several cases of prostitution inside and outside the grandstand while undertaking the research in April.

“It showed that prostitution has been happening inside and outside of the grandstand. The youngest was a 12-year-old boy, who later tested positive for an STD (sexually transmitted disease). The report should be taken seriously by those who are working for the protection of children,” Allian said.

Even bath, toilet areas

Ramada Jose, a former volunteer of Women’s Friendly Spaces that worked for the evacuees at the sports complex, confirmed Karina’s case, saying she was but among the many women in similar situations there.

Prostitution happens at almost every nook and corner of the grandstand, including the bath and toilet areas, Jose said. Worse, illegal drugs also proliferated, she added.

“These structures are used as sex dens and drug dens, so we recommended that these should be padlocked. Besides, how can we put to better use these structures when there is no water getting here,” Jose said.

The prostitution of mothers like Karina is only the tip of a more serious problem hounding the relocation of evacuees. Government officials, however, are quick to issue denials.

Minors, too

Even minors are prostituted, according to a study released by a child protection welfare group.

At Masepla Transitory Site in the city’s Barangay Mampang, there is the so-called “fish for sex.”

The assistant city health officer, Dr. Kibtiya Uddin, has heard about the reported prostitution of minors. “But when we conducted an investigation, we didn’t see anything,” Uddin said.

Karina said she never wanted to prostitute herself, but the conditions had forced her, especially when three of her children got sick “one after the other.”

Moreover, her husband, who had volunteered to build bunkhouses for the IDPs in Barangay Mariki, became ill and his condition got serious. “No one bothered to pay him or extend financial support,” Karina said.

She said she tried going around, begging for money, but the cash hardly came. So she thought of sleeping with other men for money.

Holiday food

On Christmas Eve, Karina and her family shared “noche buena” food from the money she got. For New Year’s Eve, she would do the same, she said, but still clinging to her wish for change.

“I don’t want them to know that I am into this kind of work. I am praying hard, I pray hard for God’s forgiveness,” Karina said. “I just want to go back to our old place. I don’t care if we are going to live in a tent or a shack for as long as I can raise my children with dignity and decency.”

What has been hindering the relocation of Karina’s family is the lack of documents to prove they own the property they had been occupying in Santa Catalina. Karina said they were at the mercy of the government, whose relocation project had proven to be more problematic than expected.

And until they get out of the grandstand, her being prostituted will never end.