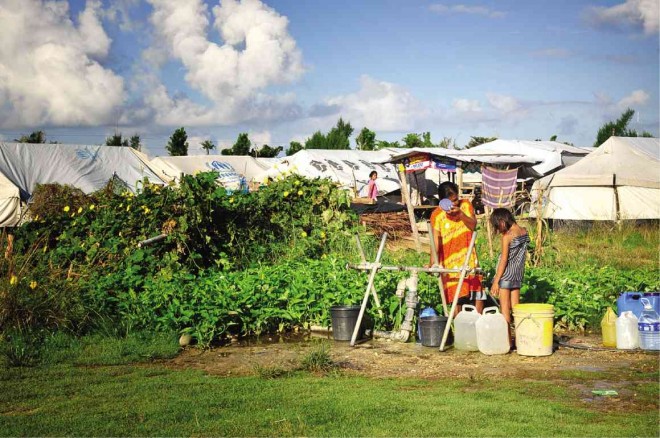

RESIDENTS fetch water from the communal water source at the “tent city,” a relocation site for seaside families displaced by Supertyphoon “Yolanda” that ravaged Eastern Visayas one year ago. MELVIN GASCON/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

When Supertyphoon “Yolanda” ravaged the coastal town of Guiuan in Eastern Samar province on Nov. 8 last year, Melojean Zulueta, 46, struggled to keep her sanity as she lost her husband, Ermelindo, and was left to take care of her six children and two grandchildren. One of her daughters was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Ermelindo drowned when he tried to save neighbors, the Oraes family, as 6-foot waves hit and submerged their neighborhood in Barangay 6.

But a year after the typhoon, Melojean and her family have yet to feel that help has come their way, even the financial aid promised them for Ermelindo’s death.

Since then, she has been looking after the needs of her family by taking menial jobs in the town, like serving as house help and doing the laundry of other families. She and her children live at the “tent city” in Barangay Salug.

The uncertainty of surviving through the day, the cries of hunger of her grandchildren and the sight of her cancer-stricken daughter, 17, in extreme pain are forcing Melojean to lose hope. “At times I find myself thinking of committing suicide to end this suffering,” she said.

Residents interviewed by the Inquirer in Eastern Samar share the disbelief and outrage because they have seen how some people, even in times of disaster, prey on typhoon victims.

‘Transitional’

On Nov. 3, the municipal government and relief organizations began activities meant to observe the first anniversary of Yolanda five days later. Part of the activities was the ceremonial turnover of what agencies call “transitional housing” to 130 families at the tent city in Guiuan.

The tent city, which occupies what used to be the athletic field of Eastern Samar State University, has been host to 135 families displaced by Yolanda from the fishing communities in Barangays 6, 7 and Hollywood.

Residents welcomed their transfer with much skepticism, wary that government people might have again benefited from the construction of the resettlement site.

It remains unclear whether the tent city will be a permanent relocation for the homeless.

Alejandre Vallescas, a Christian pastor and camp leader, said they would accept the houses anyway because they did not have a choice.

“We have lost trust in the government. Right now, we are taking everything [government representatives] are saying with much doubt because of our experiences,” Vallescas said.

Still waiting for aid

Guiuan’s tent city has been made a showpiece of the need for relief aid, Vallescas said, even drawing the attention of officials of international organizations, foreign governments, national government agencies and celebrities, like boxing champion and Sarangani Rep. Manny Pacquiao.

“Seeing our situation here made all these visitors to pledge help. Many came here, gave inspiring speeches, took a lot of photos,” he said.

But in the months that followed, after all the list-ups, signing of documents and submission of documentary requirements, residents are still left waiting for aid to arrive.

“The government has repeatedly boasted in media reports the dizzying amounts of foreign and domestic aid that had been donated for survivors of Yolanda, especially for us in Guiuan, but we are left wondering why we have not been receiving anything,” Vallescas said.

“We have strong suspicion that we are being used by some unscrupulous people,” he added.

The only cash assistance that tent city residents remembered was the P1,000 that Pacquiao handed out to each of them in December. A few others, like Charita Lacaba, received a P10,000 aid from an international humanitarian organization. She used the money for her family’s needs and as capital for a small store near the tent city entrance.

But Felipe Padual, Guiuan’s disaster risk reduction and management officer, said surviving family members of typhoon victims were given cash assistance on Nov. 3 by representatives of the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) in Eastern Visayas.

Each of the 99 families received a P10,000 cash assistance while those who were injured got P5,000 each.

Padual, however, lamented that only 37 of about 3,000 injured in Guiuan were qualified to receive the cash gift. The rest failed to meet the OCD requirements, one of which was a certification that each recipient had been hospitalized for at least three days.

Many could not come up with the requirement, Padual said, because the typhoon shut down most hospitals in Guiuan and residents could not afford the cost of confinement.

“We argued with authorities back then that the requirements be relaxed to accommodate more injured people, but our pleas were ignored,” he said.

Corruption

Some residents, who asked not to be named for fear of harassment, blamed the culture of corruption as they cited irregularities in the distribution of relief packages to survivors.

A complaint among typhoon survivors in Guiuan is how kinship and political connections supposedly dictated the distribution of donations that included materials for housing and toilets or livelihood packages like fishing boats and pedicabs.

Since many of the agencies allowed barangay officials to select qualified recipients, some village chiefs took advantage, favoring relatives and supporters while leaving out those of their political rivals.

“One can tell who the village chief’s people are by counting the number of newly built houses [donated by a foreign nongovernment organization], while those who remain in shanties are his rivals,” said a store owner in Casuguran village.

A watchman from Sulangan village said he saw how imported food items, such as canned goods, milk and candies, were replaced with local goods after these were repacked.

“When the packages came out, these were already filled with locally produced items that the DSWD (Department of Social Welfare and Development) normally gives out during typhoons. These consisted of rice, canned goods and noodles,” said the watchman, who was tasked by officials with claiming the share of goods for people in his village days after Yolanda struck.

A tricycle driver from Barangay Lupok said he was hired by another official of a relief agency to deliver boxes of imported relief items from a distribution center to his hotel room at the Guiuan town center.

A boat operator, who was contracted by a foreign relief agency to haul housing materials from the Guiuan mainland to Homonhon Island, narrated how he was made by a local staff to sign documents claiming that the rental was P15,000 for each trip but he was paid only P7,000.

“At first, the relief activities of international organizations were orderly as these were run by foreigners. Things turned for the worse when Filipinos took over,” he said.

“That is the worst part: Filipinos preying on fellow Filipinos in times of calamities,” he added.

Guiuan Vice Mayor Rogelio Cablao said municipal officials, too, had received reports of cases of irregularities involving the distribution of aid to survivors.

“With the magnitude of the devastation and the chaos in all the relief efforts, there were people who took advantage. But they were already beyond our control,” he said.

Vallescas said future donations for survivors should be given directly to the intended beneficiaries and not through any intermediary.

“That is if they want to make sure that the aid will serve its purpose. After all our experiences in the past months, at this point, we no longer trust anyone, especially politicians and people in the government,” he said.