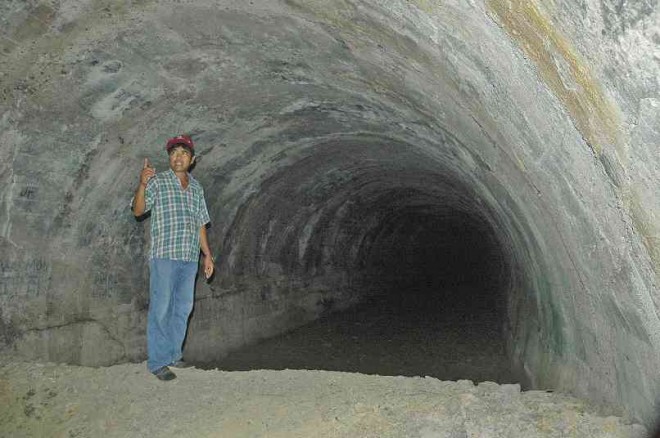

RAIL TO NOWHERE Nestor Ninnuan (left) says the abandoned tunnel of the railway track that would have run from his hometown of Aringay in La Union to Baguio City has fallen prey to treasure hunters and vandals. PHOTOS BY RAY ZAMBRANO

On top of the entrance to a concrete tunnel in Barangay Poblacion in Aringay town, La Union province, are the Roman numerals MCMXIII.

As in the olden days, structures were marked with the year when these were built, and this tunnel for a railroad system that would connect the agricultural town of Aringay to Benguet province was dated 1913.

In his 1999 book, “The Colonial Iron Horse: Railroad and Regional Development in the Philippines 1875-1935,” Arturo Corpuz said Manila Railway Co. (MRC) Ltd., a British company, started to organize the construction of the Baguio railway line in 1911.

It was a year after that the Aringay station was opened to the public. Today, the ticketing office of the station still stands and is used by residents as a warehouse for their farm products.

The Roman numerals are still clear to this day and the tunnel stands as firm as a rock, proudly defying wars, the elements, earthquakes, treasure hunters, vandals and wild plants that have grown above the tunnel.

The bronze marker, however, had been stolen, said Aringay Vice Mayor Charlie Juloya.

The 500-meter tunnel was built during the American colonial period and intended for Philippine National Railways (PNR) trains bound for Baguio City.

Financial troubles

But the project encountered financial troubles. Corpuz said the railroad company lacked capital, aggravated by costly management mistakes, such as overpriced right-of-way payments, highly paid but inefficient European workforce and sourcing of materials from Manila, with hauling charges, causing original costs to double.

The construction of the Aringay tunnel started when World War I broke out in Europe in 1914. Corpuz said the war sealed the fate of the already shaky prospects of the Aringay-Baguio line.

Although grading work was already completed, except for one of the five major tunnels, with rails and bridges already in place for up to 12 km from Aringay, the financial and labor troubles of the MRC were becoming untenable, he said. The war in Europe gave the MRC a reason to abandon the line.

Aringay-Baguio line

The Aringay-Baguio line would have started from the Aringay station, passed through rivers and mountains, until it reached Baguio, which the Americans were then developing as the country’s summer capital.

Officials of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and village leaders in Tuba town in Benguet said the plan to connect La Union and Benguet by railway might no longer push through as the old tracks had been converted into roads.

Christopher Alipe, a government engineer, said his office needed to widen the roads that would pass through the old railway line in the villages of Nangalisan, Asin and Tadiangan in Benguet, and San Luis in Baguio City, because they were anticipating that more vehicles would use this alternative route.

Pedro Guzman, village chief of Nangalisan, said some sections had been titled to private owners who built their houses there.

Nelson Tequed, 64, who was born and raised in Nangalisan, said his family and their relatives had built houses because the PNR had sold rights to the property to residents.

Tequed said the old railway line had three stations all the way to the summer capital—in a community called Gallano in La Union, Asin in Benguet and Baguio.

“We used to see sections of the railway tracks when we were kids,” he said.

Amado Hipol, 66, who was born in Gallano but now lives in Nangalisan, said the rail line would have crossed a river separating Galiano and Sablan town in Benguet and then connect to Tuba.

Hipol said the tracks in Sablan are now rice fields.

Overtaken by houses

Like most properties of the PNR, the site in Aringay, where the tracks going up to the tunnel were put up, has become a residential area.

The route to the tunnel is a virtual forest, where one would have to walk for half a kilometer beside a cliff where wild plants abound. The peaceful surroundings is broken only by the chirping of birds and sounds made by insects.

But the efforts pay off upon reaching the tunnel. The clock is turned back to the time when the structure’s construction may be one of the greatest events of those days.

And perhaps, it was an ambitious project, too, as two similar structures could also be found in the community of Asin in Tuba town in Benguet. The abandoned project would have been 40.4 km long and would have taken train passengers to downtown Baguio.

Japanese treasure

The tunnel cut through a mountain. The structure, 7.5 meters wide, was so durable that it was used as headquarters of the Japanese Imperial Army, which considered it strong enough to withstand bombings of the Americans during World War II, local officials said.

But because the Japanese soldiers stayed there, some people believed they left looted treasures in the tunnel. They dug the tunnel ground and left their debris there, creating pits and an eerie atmosphere. The tunnel’s walls were not spared as hunters tried to crack the concrete in their attempts to find the supposed Japanese loot.

“This was our playground. We would run up to the end and go back to the entrance where we could see our carabaos grazing,” said Nestor Ninnuan, 54.

But there is no more grazing ground around the tunnel. Instead, vegetation has taken over the place.

The local government cleared the area a year ago, said Ninnuan, a municipal employee who lives near the tunnel. It proposed to buy the property from the PNR or have the state company donate it so a historical and ecotourism site could be established there.

Since the tunnel is located on a mountain overlooking the Aringay River, the local government wanted to incorporate the site in its ecotourism project that would include zip lines, Juloya said.

But the PNR turned down the request of the local government to acquire the property through sale or donation. This was because it was “planning to upgrade the railway infrastructure so we can provide train services again toward North Luzon,” PNR General Manager Joseph Allan Dilay said in a letter to Juloya in March.

“While we are in the process of finalizing such plans, we regret to inform you that we cannot act on your request at this time. We caution you that your intent to occupy and introduce improvements upon PNR properties is a clear violation of the law,” Dilay said. With a report from Jhoanna Marie Buenaobra