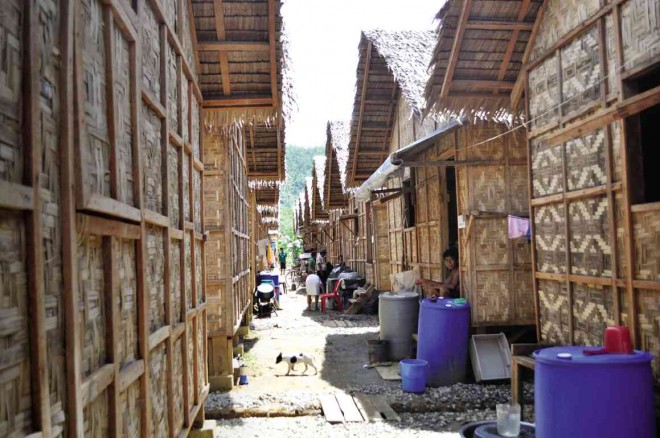

THE SO-CALLED transitional houses for survivors of Supertyphoon “Yolanda” are made of nipa and bamboo. While beneficiaries say these are better than leaky tents, the place where these were built is far from where they earn a living. CONTRIBUTED PHOTOS

Rosalina Ocenar and her family may now be sleeping better at night and feeling safe from storm surges like those unleashed by super typhoon “Yolanda” (international name: Haiyan) almost 10 months ago, but one problem is bothering them—where to get food.

The Ocenars are among 60 families displaced by the super typhoon who were moved in July to so-called transitional houses built on a 1-hectare lot in Barangay Santo Niño in Tacloban City. They used to live in bunkhouses or tents after their houses in San Jose District were destroyed by storm surges.

“We cannot ask for food from our neighbors like we do in San Jose because we know that they are also hard up. There are instances when we eat only once a day,” Ocenar said.

“Unlike in tents, we can now sleep soundly even when it rains,” she said. “The only problem,” she added, “is where to get food.”

More than 2,000 families are still living in tents in San Jose, as well as in Sagkahan and Magallanes areas.

Main livelihood

Most of the families in the coastal community of San Jose depend on fishing for their survival. But from their dwellings in Santo Niño, the nearest fishing ground is at least 24 kilometers away and a round-trip fare costs at least P40.

THE TRANSITIONAL houses built, not by the government, but by a nongovernment organization offer some degree of comfort for “Yolanda” survivors.

The transitional houses were built by Operations Blessing, a nongovernment organization. These look like nipa huts built from shingles, amakan or bamboo matting and coconut lumber, with a floor area of 18 square meters.

The typhoon-displaced families are occupying the half-way houses while they await permanent houses under construction on a 10-ha property just

100 meters away, said Danilo Naputo, community facilitator of Tacloban’s housing and community development office.

Naputo said concern for safety was the reason the city chose to build the transitional and permanent houses on flat land in Santo Niño.

Storm surges are not likely to occur because the area is far from the coastline. Since the houses are built on flat land, these will not be hit by landslides or mudslides. There is also no fault line there.

No food, money

Ocenar, 47, acknowledged that her family feels safer living in the transitional house, their home for two months now.

But Santo Niño, a residential zone, is inland and has no farmlands.

In March, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) stopped the distribution of relief and shifted its efforts to the rehabilitation phase of post-“Yolanda” rebuilding.

Naputo said a local official had tried to negotiate with the DSWD to give at least half a sack of rice to each of the 60 families until they are transferred to the permanent houses.

Rosita Enales, 57, whose husband Reynaldo died when “Yolanda” struck, said the transfer to the transitional houses only worsened her financial difficulty.

Enales, who lives with her six children, used to sell food in San Jose. When the family transferred to Santo Niño, she opened a small sari-sari store using P15,000 in financial assistance, which she received from Tzu Chi Foundation.

“I was forced to close it down because I had nothing more to sell since whatever money I earned, I used it for our daily needs,” the widow said.

Edgardo Pedrosa, 56, also lamented the difficult life in the resettlement center.

“I used to work as a vendor. Aside from having no income to start again, the area where we are right now is quite far from the city [proper],” Pedrosa said.

While he appreciated the government’s effort to help, money was hard to come by, said the father of five children.

Naputo said the families were told what to expect even before they were transferred to their transitional houses. “We did not promise them a better living condition right away. However, we are doing all we can to help them,” he said.

City officials are now doing a survey of people staying in the temporary shelters to find out what type of livelihood best suits each of them.

Naputo said the government also hoped to transfer them to the permanent houses before the year ends.