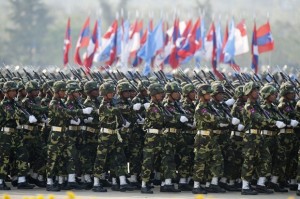

Members of Myanmar’s military march in formation during a ceremony to mark the 69th anniversary of Armed Forces Day in Myanmar’s capital Naypyidaw on March 27, 2014. AFP FILE PHOTO

YANGON, Myanmar — Four reporters and the chief executive of the magazine they work for were sentenced Thursday, July 10 to 10 years of hard prison labor for violating Myanmar’s national security by writing and publishing stories about a weapons factory.

The court sentenced the five men for violating the 1923 Burma State Secrets Act pertaining to trespassing in a prohibited area with prejudicial purpose. The law was enacted when Myanmar was a British colony called Burma.

The weekly Yangon-based Unity journal published stories in late January alleging the military had seized more than 3,000 acres (1,200 hectares) of farmland in Myanmar’s central Magwe Region to construct a weapons factory. It reported allegations that the factory would produce chemical weapons, also printing a denial by authorities of the latter allegation.

The authorities defended the arrests as a matter of national security. The magazine has since gone out of business.

Myanmar has made sweeping reforms, including freeing the press, after emerging from a half century of brutal military rule in 2011. But media watchdogs say reporters still face intimidation and arrests, especially in rural areas, and that the situation appears to be worsening, even as official censorship has been lifted.

The human rights group Amnesty International described the court’s action as “a very dark day for freedom of expression in Myanmar.”

“These five media workers have done nothing but cover a story that is in the public interest,” Rupert Abbott, Amnesty’s deputy director for the Asia-Pacific region, said in a statement.

After the arrests, Deputy Information Minister Ye Htut acknowledged that the factory belonged to the Defense Ministry, but told The Irrawaddy, a Thailand-based online news site, that claims it had anything to do with chemical weapons were “totally baseless.”

“The journal only quotes local people,” Ye Htut said, defending the arrests of journalists following allegations that the government was starting to trample on newfound press freedoms. “It is a national security issue, and even a country like the U.S. would respond the same way on these matters.”

Kyaw Lin, the lawyer for Unity chief executive Tin San, complained bitterly Thursday about the verdict being “totally unfair,” and suggested that it was not appropriate to use a law that he said was intended to apply to spies.

“These people are not spies in this case. They were just reporting,” he said, adding that the law says nothing about trespassing on army land, and that any infraction might have been more justly punished by a fine and two or three days in jail.

Amnesty’s Abbott said the sentences “expose the government’s promises to improve the human rights situation in the country as hollow ones. They reflect a wider crackdown on free media since the beginning of the year, despite government assurances that such practices would end.”

He described the convicted men as political prisoners and called for their immediate release.