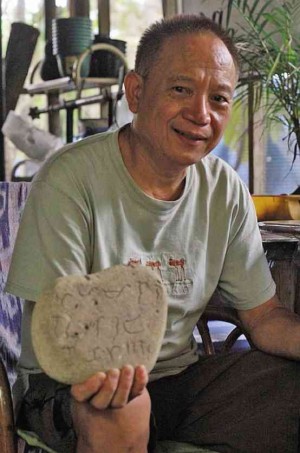

ANTHROPOLOGIST Francisco Datar holds a replica of one of the Monreal Stones, now the centerpiece at the Baybayin Section of the National Museum. PHOTO BY JUAN ESCANDOR JR.

For nearly 11 years, pupils of Rizal Elementary School on Ticao Island in Monreal town, Masbate province, had scraped the mud off their shoes and slippers on two irregular shaped limestone tablets before entering their classroom. Little did they know that the slabs are now among the centerpiece artifacts of the National Museum.

Officially called the “Monreal Stones” after the town these were discovered, the artifacts contain scripts believed to be a variation of the Baybayin, the ancient native script documented and used by Spanish friars to popularize religious teachings among early Filipinos.

The rare finds are displayed at the Filipino Ancient Script section of the National Museum, which claimed the items in 2012 a year after their significance was established. The bigger piece, which weighs 30 kilos, is 11 centimeters thick, 54 cm long and 44 cm wide while the other is 6 cm thick, 20 cm long and 18 cm wide.

Mary Jane Louise Bolunia, officer in charge of the museum’s Archaeology Division, says the limestone pieces contained 156 scripts, the biggest number compared with those engraved in artifacts under its care and protection. These are “important in the study and raising awareness on Baybayin, and will encourage enthusiasts to learn the ancient script,” she says.

More scripts

The Monreal Stones are made of solid limestone compared with the five artifacts in the museum collection whose scripts are engraved in copper, tin, ivory and clay—the Laguna paleograph, Butuan tin paleograph and two ivory seals, and the Kalatagan clay pot from Batangas.

Bolunia says the museum learned about the ancient stones from professor Francisco Datar of the University of the Philippines’ Department of Anthropology. She and Wilfredo Roquillo, a former curator of the National Museum, went to Monreal to investigate and found that the place near the school where the stones were found was “already disturbed.”

The place was quarried of stones used in road building.

Dr. Jeremy Barns, National Museum director, and his assistant, Angel Bautista, examined the artifacts and brought these to Manila for protection and further study.

According to Datar, teachers and pupils of Rizal Elementary School would scrape the mud off their slippers and shoes on the bigger limestone slab that was on top of the smaller one, which were laid on the doorstep of the Grade 4 classroom.

Cleaning the stones

Monreal Stones now the centerpiece at the Baybayin Section of the National Museum. PHOTO BY JUAN ESCANDOR JR.

That was until March 15, 2011, when Virgie Almodal, then the new school principal, noticed something remarkable about the muddied stones. She ordered her pupils to scrub the dirt off the stones so these could be displayed on a platform at the school grounds.

For several weeks, the stones were laid there until Almodal was prodded by community members to keep them to ensure their safety from vandals.

“On April 15, 2011, while on a boat trip in Masbate, school principal Virgie Almodal and her husband were showing to fellow passengers two photographs of the stone tablets found in the school,” Datar recalls.

The professor’s cousin, Sue Arizala, a retired principal who lives on Ticao Island, was also a boat passenger and offered the Almodals to facilitate a meeting with him.

Datar learned during the meeting that Almodal had previously attended a seminar sponsored by the National Historical Institute, which was why she showed unusual interest on the symbols inscribed on the limestone pieces.

The tablets

The professor first saw the artifacts on April 28, 2011, when he dropped by Ticao on his way to Eastern Samar. The bigger piece is a flat rock, light brown and roughly triangular with early Filipino script written on both sides, he says.

The letters are written in a horizontal pattern and when he closely examined the tablet, portions were missing on the left and right sides and at the bottom. “They (missing pieces) are the key to the actual size of the stone,” Datar says.

The second stone is smaller, lighter and ovoidal. “Most likely, the stone material is the same as the bigger tablet. The writings are only on one side,” Datar says.

He immediately informed the National Museum after making his initial examination.

Datar gathered professors from different departments in UP units in Diliman, Quezon City, and Mindanao, all experts in their fields, to form the Ticao, Masbate Anthropological Project Team.

The group included Ricardo Nolasco (Departamento Ng Linggwistika), Arnold Azurin (Archaeological Studies Program), Ramon Guillermo (Departamento ng Filipino at Panitikan ng Pilipinas)—all from UP Diliman; and May Anne Mata (Departamento ng Matematika, Pisika at Agham Kompyuter) and Mayfel Joseph Paluga (Departamento ng Agham Panlipunan)—both from UP Mindanao.

Maricor Soriano and her 3D team at the National Institute of Physics in UP Diliman later joined the team.

In June 2011, the team conducted the first of a series of fieldwork. They interviewed people who were among the discoverers of the limestone artifacts. A thorough archaeological mapping was also done in the site where the stones were believed to have been extracted.

The results of their work were made public in a conference attended by members of the academe, officials from the Department of Education and local government units of Ticao on Aug. 5-6, 2011.

In a scientific paper published the following year, Guillermo emphasized that the team’s transcription process “did not include the matter of deciphering (or reading) the inscriptions.”

Nolasco says the engraved scripts have been identified as Baybayin by many members in the team. “The markings may mean virama or the cross symbol placed on different sides of the script that ‘killed’ the inherent vowel ‘a’ on consonant scripts,” he says.

“The engraved scripts on the limestone pieces were definitely done using blunt metal instrument and that it could be probable that the scripts were etched by different persons or one person over a period of time,” Soriano says.

The 3D imaging of the engraved scripts helped in differentiating the original markings from recent ones, such as the scratches made by hardware-bought nails used by the pupils to get rid of the dirt from the engravings.

Hoax?

Datar says the information on the two stones created quite a controversy when it reached the academe and stirred popular imagination in 2011. Some people declared the stones to be a hoax, but he challenged them to prove their claim.

Guillermo says “nothing from the fieldwork surfaced that can be prima facie evidence that the stones with inscriptions are fake or hoax created by anyone.”

Datar acknowledges difficulty in authenticating the creation date because the limestone pieces were dug up in the year 2000 without following standard scientific methods.

Soriano says the discovery had posed bigger questions as to their creation date, what do they say, and what they stand for.

“The big questions on the Baybayin script would continue to boggle scholars and scientists,” she says.

The tablets were found by pupils who were ordered by their teacher to gather stones to step on before entering the classroom so they could avoid wading through the ditch when it rained, says Datar.

On June 17, 2011, he met with National Museum officials so that the study and eventual transfer of the artifacts from Masbate could begin.