LUCENA CITY—Recollecting the pain and sufferings they endured during the dark years of Marcos rule in exchange for getting financial reparations from the state has become another agonizing experience for victims of human rights abuses from Quezon.

Close to 700 survivors, mostly farmers from remote areas of the province, trooped to Kalilayan Hall, a government multipurpose hall in Lucena City, on June 16-17, spending the night on the concrete floor of its porch, just so they could submit documents and their personal narration of their ordeal during the years when deposed President Ferdinand Marcos governed to the Human Rights Victims Claims Board (HRVCB).

The HRVCB is tasked with facilitating the distribution of the P10-billion compensation for victims of human rights violations during the Marcos regime.

‘NPA rebel’

Alicia de los Reyes, of Guinayangan town, said her father Roberto, 69, avoided recalling his experience when he was arrested in 1980 on suspicion of being a New People’s Army (NPA) rebel.

Holding a cigarette stick, Roberto sat beside his daughter as he silently stared at other victims around him.

Alicia asked that her father be spared another harrowing moment as the Inquirer tried to strike a conversation with him on that chapter of his life.

She said her father cried to his family when he remembered the “unbearable physical and mental torture” he suffered for two weeks in the hands of his captors.

It was emotionally draining for him, Alicia said.

The family, nonetheless, had to provide all the sordid details if only to prove to the government that their father was indeed a victim claimant, she added.

Abducted

Erlinda Rodriguez, 76, of Barangay Vegaflor in Lopez town, recalled that her younger brother Pepito was abducted by Army soldiers on Dec. 25, 1985.

“He was then pulling a pig to be butchered for Christmas celebration. But instead of the pig, he was the one butchered by the soldiers,” Rodriguez said.

Her brother bore multiple stab wounds in different parts of his body, she said. “His mouth was stuffed with torn pieces from his shirt.”

Rodriguez was seeking reparation for her brother who had died single.

Onofre Datario, 64, of Barangay Villa Espina, also in Lopez, recalled how he was forced to eat horse manure by his military captors after his arrest in 1984.

He said a big group of Army soldiers raided his village and tied the hands of more than 20 men. The captivity lasted three days and three nights.

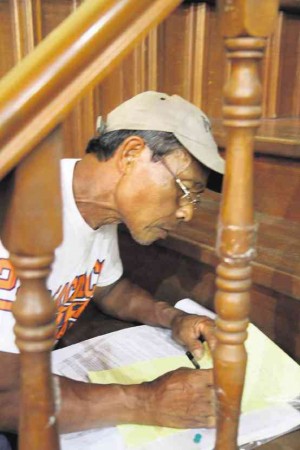

HUMAN rights victims, mostly farmers from remote areas of Quezon province, gather at Kalilayan Hall in Lucena City on June 16 and 17, to submit to the Human Rights Victims Claims Board documents and personal narration of their torments during the dictatorial regime of deposed President Ferdinand Marcos.

Some of the men were freed after they signed papers attesting they were not harmed, Datario said. “Four of us did not sign so the soldiers jailed us,” he said.

He held back tears when he recalled that during one of the many torture sessions, he could no longer control himself from releasing his bowel.

Datario said he spent more than a year inside the Quezon provincial jail in Lucena on trumped-up charges of being an NPA rebel.

If the government would not provide him with reparation pay for his sufferings, “it is still all right with me,” he said.

Warrantless arrest

Leonor Sevilla, 82, a native of Lucena, was arrested by Army soldiers on Jan. 16, 1982, in Mati, Davao Oriental, without being served any warrant.

“I was a lay missionary and catechist in Davao when I was arrested,” said Sevilla, now a religious worker at Saint Ferdinand Cathedral in Lucena.

For 13 months, she was incarcerated at a military stockade in Davao and suffered various forms of mental torture.

“I was lucky one Army official, who was once a student of my sister, recognized me. That spared me from the painful physical torture,” she said.

Sevilla said she would give to the needy the cash reparation she would receive.

Claims

Lawyer Ida LaO, head of HRVCB team in Lucena, said close to 400 persons had filed their claims during the two days.

They had to return before the deadline for submission in November to accommodate hundreds of others who were unable to bring their applications, she said.

Submission of claim application started on May 12 and will end on Nov. 10. The victims’ failure to file claims during the six-month period, as provided by Republic Act No. 10368 or the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013 would be deemed a waiver.

Applicants must submit personal accounts of human rights violations and provide pieces of evidence to support their claims.

“Most often, the evidence were provided by jail mates of the claimants and personal witnesses during the commission of the human rights violation,” she said.

LaO admitted that there were attempts by pseudoclaimants in Pampanga to submit dubious claims. “The claimants don’t know the version of the incident in their affidavit. Apparently, they are just dummies. It is now being investigated,” she said.

The agency has yet to encounter similar incidents in Quezon.