Since 1949, when the University of the Philippines (UP) moved to Diliman, Quezon City, until 1984, the university’s summa cum laude (SCL) graduates on its main campus numbered in single digits.

The highest numbers of summas during that period, nine, were registered in two consecutive years, 1982 and 1983.

Over the same 35-year period, there were 14 years when there was not a single graduate who qualified for the highest academic honor, which requires a weighted average grade (WAG) of at least 1.2. In fact, there was an eight-year stretch—from 1964 to 1972—when there were no summas.

In 1985, Diliman had its first double digit number of SCLs: 11. But it was followed the following year by a single honoree, the last time UP Diliman would have a single SCL graduate.

The next 18 years would see SCL graduates in single digits. In 2005, the number rose to 10, then 12 in 2006 and dropped to eight in 2007.

But it was not until 2008, UP centennial year, when the campus gave the honor to 15 graduates, that many alumni started to raise questions about qualifications for academic distinctions.

Between 2008 and 2014, during the terms of president Emerlinda Roman and the incumbent Alfredo Pascual, who replaced her in 2011, UP had 132 SCL graduates (15 in 2008, 17 in 2009, 25 in 2010, 21 in 2011, 19 in 2012, 15 in 2013 and 20 in 2014), nearly 42 percent of the total 314 SCL graduates in Diliman since 1949.

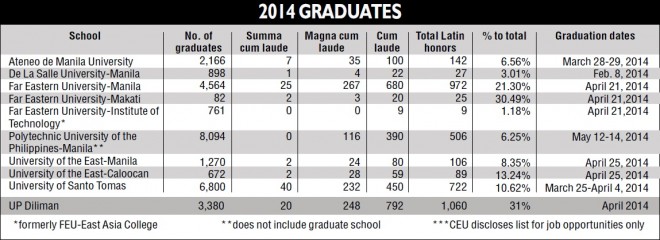

With 248 garnering magna cum laude (MCL) honors (1.21-1.45 WAG) and 792 cum laude (1.46-1.75 WAG), an estimated 31 percent, or one out of every three of the 3,380 members of Class 2014 who received bachelor’s degrees, were honor graduates.

The percentage was higher than the 29 percent the year before.

In stark contrast to Diliman’s 20, UP Manila only had one SCL in 2014. The last time Manila had a summa cum laude graduate was in 1998. Between 1986 and 1997, nobody merited the honor.

UP Los Baños only had one SCL this year, one last year, two in 2012 and none in 2011.

Rare species

Many Diliman alumni are dismayed by the apparent ease by which honors are given by the main campus of what remains arguably the premier university in the country.

For ordinary graduates, the fact that the UP summa cum laude was a rare species gave their own diplomas added value and luster. The university’s stinginess in giving out honors meant surviving UP was a feat in itself.

The freshman attrition in the past was usually high after the first semester. After the first year, even more students left UP Diliman.

So what changed on the 65-year-old Diliman campus? Has academic excellence been compromised? Or are today’s students much more superior to their predecessors? If so, is it a matter of nature, nurture, technology, or all of the above?

Do parents who find time to mentor make a difference? Have tutorial centers improved students’ study habits? Have the Internet and newfangled technology and gadgets made studying more efficient and effective?

And where are the “terror” professors who used to thwart the most determined efforts to get grades that would merit even modest cum laude honors? Have they gone extinct?

Some parents who graduated from UP and whose children finished with distinction attributed the surge in the numbers of honor graduates to their being more proactive guardians who tutored and mentored their kids. They also acknowledged the help of modern technology and gadgets, as well as tutors.

New dynamics

But for some former and current faculty members, the current dynamics of instruction at UP may have a more significant impact.

Grace Shangkuan-Koo, an associate professor of educational psychology, says nature might have helped.

“IQ does increase over generations. This is called the Flynn Effect,” she says. For every decade, IQ increased by three points in the American population.

New technology has been giving students easy access to books and updated information not available to older generations, she says. Having to do actual research in a library puts constraints on access and time, which was a great disadvantage to the older generations.

Koo says there are also students who are really smart. “They have learned the science and art of learning and are excellent in communications and networking. I do not discount the fact that there are really motivated students out there who know the value of education and are ambitious enough to reach their goals…,” she says.

She also gives credit to parents who give not just financial but also moral support, allowing their children to gain the best resources and experiences.

But of seemingly greater significance is the so-called grade inflation, which is happening in universities all over the world. She cites studies that show that at Harvard University in 1950, only 14 percent got the grade of “A.” By 2005,

23.7 percent got a grade of A and

25 percent a grade of “A-” or one in two was an A student.

Need to be ‘nice’

Koo says grade inflation is also due to a “lack of judiciousness in grading,” especially “when teachers want to be considered nice.”

UP professors are now graded by students. The Student Evaluation of Teachers is required at the end of every semester and forms part of the input in considering a teacher for promotion.

As for “terrors,” Koo says they may have a problem filling their classes, which can be canceled for lack of students.

Students, of course, give terrors a wide berth, choosing easy courses and electives and going for teachers “known for soft grading.”

In the past, word of mouth informed students of the teachers to avoid. These days, social media—Facebook and Twitter—allow students to share information on generous grade givers.

A retired professor, who was part of the team that drew up the UP College Admission Test (UPCAT) but has asked not to be identified, says teachers want to be popular so UP’s terror professors are gone.

She says that while passing the UPCAT is difficult, it is easier now for students to remain in the university.

Retired journalism teacher Rolando Fernandez, chief of the Inquirer Northern Luzon bureau, says “‘grade inflation’ has affected UP, even its elite quota course programs, for the past 10 or more years.”

He says he knows teachers who would not give a grade lower than 1.5. During one graduation, he says, half of the class received honors, which probably made nonhonor graduates feel insecure.

Inquirer columnist Randy David, UP sociology professor emeritus, does not think UP students are much smarter than before but it is definitely easier to get higher grades.

He says grade inflation is “far more complex in its causes and consequences than most people think.”

David considers technology both a blessing and a bane.

The Internet has drastically reduced the effort that goes into writing term papers but “plagiarism is a big problem” though it does not get the attention it deserves.

The retired professor says students would simply download materials so that “sometimes they did not even know what they wrote.”

An alumna says this was how National Artist N.V.M. Gonzales described some papers submitted to him when he was teaching at UP—the writers simply built a barong-barong (shanty), “getting their materials here and there.”

While David would not call terror professors extinct, he says they are a vanishing breed.

“Besides, students have more rights today. And they’re also more assertive in denouncing unreasonable teachers,” he says. “Terror teachers are more likely to be avoided than those who are merely incompetent. Students … tend to seek professors who are known to be generous and liberal with grades.”

Like Koo, David also believes teacher evaluation by students is another factor that contributes to higher grades. “Every faculty member is evaluated by his or her students just before the end of the semester. One’s score in this area could determine one’s chances of getting tenure or promotion. It is difficult to say whether popular teachers obtain good evaluation scores because they’re really good, or because they’re known—and expected—to give high grades,” says David.

But he also believes there has been a shift in teaching philosophy with “many professors and instructors [thinking] that grades are not a gauge of academic ability.”

These teachers, he says, do not assign much value to what the grades are meant to signify. Unfortunately, the result is grade inflation.

“Teachers are more inclined to give high grades to everyone, since that’s what makes most students happy.”

He says grade inflation is an issue in almost every department at UP.

Two e-mailed requests for interviews on the issue with the UP public affairs officer went unanswered and no one from the UP Alumni Association wanted to make a statement. With a report from Inquirer Research