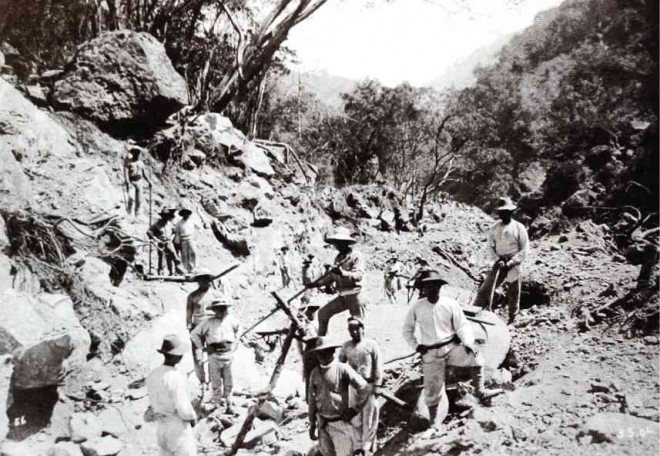

A 1904 PHOTOGRAPH from the collection of the US National Archives shows Japanese laborers at work on a slope in Camp 3 in Benguet province during the construction of the Benguet Road.

For many, World War II is remembered for its pain, untold suffering and death. Elders would advise their children not to forget these so they can continue to learn from history and not repeat its mistakes.

But public remembrances of the last war were generally based on postwar Hollywood movie perception where the Japanese and the Germans were portrayed as villains.

For some Japanese-Filipino descendants in Baguio City and the rest of the Cordillera, looking further back, before World War II broke out, would help heal the wounds of the last war, which left victims from both sides.

A book by Japanese-Filipino descendants cites the good, old days or “the long, warm and fruitful relationship in the prewar years, the prosperous years of ‘peace time,’ between Japanese contractors, farmers, gardeners, sawyers and businessmen with American and Filipino clients and overseers.”

The 330-page “Japanese Pioneers in the Northern Philippine Highlands” was referring to the early 1900s when the Americans had to import overseas labor to build the Benguet Road (later called Kennon Road). This road was vital to the Americans, who eventually succeeded where the Spaniards, the country’s colonizers for almost 400 years, failed—to take a foothold of the resource-rich Cordillera.

Among the over 4,000 workers, most of them Filipinos, who built the American project to connect the Manila-Pangasinan railway to Baguio, were Japanese, Chinese, Mexicans and 43 other nationalities.

After the final phase of the Benguet Road construction in 1905, some of the Japanese workers stayed as did some of the other nationalities such as the Chinese.

Select group

The Japanese who opted to stay were a “select group for they had experienced the strenuous work and extremely hazardous conditions of the road construction that started in 1901,” said the book’s editor and one of the authors, Patricia Okubo Afable.

As Baguio’s economy boomed after the Benguet Road was built, the Japanese—who were skilled carpenters, masons, road workers, agriculturists and traders—joined American soldiers who had been discharged after serving in the Philippine-American War.

And so did Chinese laborers and traders, and Ilocano, Pangasinan and Tagalog teachers, government officials and dealers of foodstuff, textiles and sundry goods.

The news of wage work in construction and in the gold mines operated by American soldiers-turned-gold prospectors also attracted other upland folk from the Cordillera, joining their native Ibaloy compatriots.

Multicultural

From Baguio’s booming economy in the early decades of the 1900s emerged a highly multicultural community. This was the context in which the Japanese who stayed found themselves in.

Armed with their skills and industry, the Japanese found their place in Baguio and neighboring areas whose development and progress they helped establish.

Their skills in carpentry, masonry and how to operate sawmills were put to good use as the Americans, after the Benguet Road construction, had to build the necessary infrastructures for a vacation and health resort.

Infrastructure projects from the American colonial government began to dwindle by the 1920s. But by this time, the tourist trade boomed and there was a demand for hotels, lodging houses as well as summer residences and business establishments, providing opportunities for Japanese carpenters and artisans.

IN THIS 1903 photograph from the collection of the US National Archives, workers, who included the Japanese, prepare a rock wall for blasting at Hann’s Cliff in Camp 1 during the construction of the Benguet Road (later called Kennon Road). PHOTOS FROM “JAPANESE PIONEERS IN THE NORTHERN PHILIPPINE HIGHLANDS”

For their growing families, the Japanese, many of whom had married Ibaloy women, had to supplement their incomes by tending extensive gardens, managing small stores and taking on other carpentry piece-work, such as repairing furniture.

“This was a pattern that lasted their lives in Baguio,” wrote Kathleen Okubo and Afable.

The gardens and poultry farms they established in Guisad and Lucban (both in Baguio) and in nearby La Trinidad town in Benguet helped establish the seeds of today’s vegetable industry.

Erasing good memories

“However, for Baguio people and other Filipinos, the great suffering at the hands the military during the Japanese Occupation (1941-1945) erased all good memories of Japanese neighbors, employees and associates,” Afable wrote.

This was precisely why Afable and seven other writers, most of them Japanese-Filipino descendants, came out with the book, which was published in 2004.

“In the face of anti-Japanese feelings in the years after the war, the stories recorded here [in the book] have been suppressed and denied, waiting for the healing of the wounds of war,” Afable said.

No wonder, few Filipinos, she said, are aware of the roles of Japanese individuals and associations in the growth of Manila and other Philippine towns and cities during the American period.

She cited the “poor recognition” of early development of the abaca industry by Japanese laborers, technicians and businessmen.

“Fewer still know the participation of Japanese labor in building the Benguet Road and the Naguilian Road … or of their role in helping build Baguio City and nearby provinces,” she said.

Also still unknown to other Filipinos is that some sons of those Japanese, who settled in Baguio and nearby areas, enlisted in the Philippine-US military forces and fought alongside the Allied Forces in Bataan, Afable said.

A big number joined the anti-Japanese

resistance and enlisted in northern Luzon guerrilla units as they were formed in 1944.

“Not surprisingly, the families who had sons in the Philippine-US forces suffered long periods of investigation and sometimes torture, by the Japanese police,” she said.

But these same sons and their families were to become prisoners of war under the Allied forces, and to be charged with collaboration with the enemy, Afable recounted in an epilogue of World War II (1941-1945).

Stories finally told

While such is one of the tragedies of war, the book, on the other hand, told of other stories that can warm the heart.

For example, the late Baguio Midland Courier editor Cecile Okubo Afable wrote about how the early Japanese pioneers in the highlands, despite language barriers, were able to win the hearts of Ibaloy women.

“You husband me, I wife you, I die my carabao,” a Japanese man told an Ibaloy woman in Pico, La Trinidad. And somehow, through the universal language of love, the young Japanese, who had no intention to return to his country after helping build the Benguet Road, was able to “wife” the Ibaloy woman.

Many young Japanese men, Cecile Afable wrote, got attracted by the local

women’s “long, thick black hair that fell upon their shoulders, fuller bosoms … and more rounded butts … as they marveled at the heavy loads they carried on their heads and in their baskets.”

As they married local women, the Japanese, who were among the first “overseas workers” employed by the Americans during peace time, eventually got fully integrated into the local community.

But because of the last war, the stories of the Japanese pioneers, including how they helped build Kennon Road, the summer capital and their stories of their love for local women have been suppressed for decades, whispered only among families of descendants.

Published by the Filipino-Japanese Foundation of Northern Luzon, the book about the Japanese pioneers, which came out 49 years after World War II ended in 1945, promises to deliver all things suppressed during the war years.