Finding ‘tugasi’ on Colibra Island

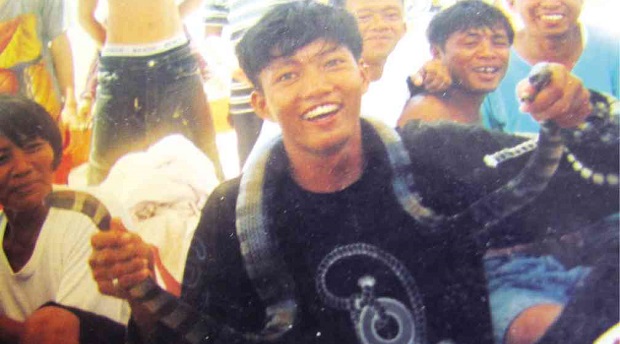

ZUMA? Nick Vilda puts a “tugasi” (sea snake) around his neck in this photo taken in 2002, when sea snakes could easily be found on Colibra Island. PHOTO REPRODUCTION BY YOLANDA SOTELO

It was summer of 2002. Nick Vilda and his friends were having a picnic on Colibra Island (Snake Island) in Dasol town in Pangasinan province. While spearfishing, a “tugasi” (sea snake) slithered near Vilda. He grabbed its head and brought it ashore.

He draped the meter-long tugasi around his neck, imitating Zuma (a Filipino comic book character featuring a man who has snakes protruding from his shoulders), holding its head with one hand and the tail with the other. His friend coiled a shorter snake around his arm. The cameras clicked, the friends freed the tugasi and they went about their merrymaking.

“There were plenty of tugasi then on the island,” Vilda, 32, said. “We would spend nights there and the sea snakes would crawl near the bonfires, as if attracted to the light and warmth.”

The sea creatures could be found anywhere on the island then but mostly they hid in crevices and spaces of corals and stones.

That summer of 2002 would be the last of summers when Vilda and his friends communed with snakes. “That time, they were actually already getting fewer. When we went there in 2010, we did not see any tugasi anymore,” Vilda said.

Residents of the coastal village of Tambobong believed that taking tugasi to the mainland would result in death to the taker. While sea snakes are venomous, not one Dasol resident was reported to have died from being bitten by these creatures, Vilda said.

Colibra Island is a two-hectare coralline island, located 8 kilometers from mainland Tambobong. It cuts a solitary figure on Dasol Bay, its white beaches seemingly crowned by green vegetation visible from afar.

While the island is owned by the Vilda family, everyone is free to come and enjoy its beautiful surroundings, said Rodolfo Vilda, 68.

Rodolfo, a Tambobong barangay (village) council member and Nick’s uncle, said the island originally belonged to his grandfather but the family has given him the task of taking care of it.

He said he used to bring his children to the island for adventure. There they would encounter the sea snakes, both in the sand and water. They have seen snakes as long as 2 meters (6.5 feet) slithering through the water.

“They won’t hurt you if you don’t hurt them,” he said.

No one could explain how and why the sea snakes began disappearing from the island.

Rodolfo said the snakes could have been caught for pulutan (appetizer) or as pets. “Since the island is not guarded and anyone can come, it was possible that some visitors came to collect them, until they were all gone,” he said.

Harrie Cornel, 62, a resident of Dagupan City, said he was once gifted by a friend with a tugasi that he put in an aquarium and fed with fish feed.

Cornel said he gave the snake away when a television program featured Colibra Island and its snakes and warned people that the reptile was highly venomous.

Rodolfo said he believed that the influx of people during summers may have driven the sea snakes away to the Crocodile

Island. The island, named as such because of its shape, is near the mainland but has only a few meters of beach, making it unattractive to swimmers.

Last month, the Inquirer, Rodolfo and his daughter,

Rhoda Banay-an, and some residents went to Colibra Island. The mission: Find a tugasi.

The group failed to see one, even as they peered under the rocks and plants. No snake gliding in the crystal-clear water, either.

“We will try to look at the Crocodile Island,” Rodolfo said.

A short stop at the Crocodile Island proved successful. The team found a tugasi, less than 2 feet long and about a half inch in diameter, with its distinctive white and blue band from its head to tail visible in the clear water.

Rodolfo, lamented the loss of sea snakes on Colibra Island. He said they would collect some at the Crocodile Island and bring them to Colibra, their original habitat.

Then they would have the island guarded from poachers, especially during summer when hundreds would daily flock to the island, so the tugasi would once more thrive there.

But it’s not only poachers that are “enemies” of the island, Banay-an said.

Visitors leave their garbage that not only pollute the island but could also prove dangerous to marine life. Some also collect corals and stones and haul these in sacks.

“There is a big work to do to preserve the beauty of the

island. We plan to put signs around about what visitors can and cannot do while on the island. We may also collect a minimal fee and the money would go to paying the guards and cleaning the surroundings,”

Banay-an said.