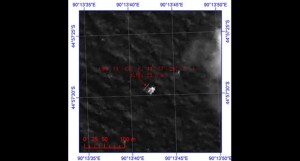

This image provided by China’s State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense shows a floating object seen at sea next to the descriptor which was added by the source. The image was captured around noon, on March 18, 2014 (Tuesday) by a Chinese satellite in S44’57 E90’13 in south Indian Ocean. It shows what is suspected to be a floating object 22 meters long and 13 meters wide. It is about 120 km south (slightly to the west) of the suspected objects released by Australia. AP

SINGAPORE—The location of missing Malaysian plane was narrowed down through the detailed study of hourly ‘pings’ said satellite company Inmarsat on Monday.

The increased complexity in charting out this information was also the reason why it took two weeks before any solid conclusions could be reached, it added.

According to a report from The Telegraph, the MH370 continued to send out hourly ‘pings’ despite the main aircraft communications system being turned off. These signals are normally used to synchronize timing information.

By studying them, Inmarsat was able to determine that the plane flew for at least five hours after leaving Malaysian airspace, and that it could have potentially taken two routes.

Chris McLaughlin, senior vice president of external affairs at Inmarsat explained to The Telegraph, “Effectually we looked at the Doppler effect, which is the change in frequency, due to the movement of a satellite in its orbit. What that then gave us was a predicted path for the northerly route and a predicted path the southerly route.”

Although Inmarsat relayed this information to Malaysian authorities on March 12, it continued to crunch the data.

Since then, comparisons were also made with other aircraft on similar routes, and Inmarsat was able to establish an “extraordinary matching” between its predicted path to the south, and readings it received from other planes.

This information, coupled with the plane’s assumed speed, narrowed the search area down to 3 percent of the southern corridor.

“We worked out where the last ping was, and we knew that the plane must have run out of fuel before the next automated ping, but we don’t know what speed the aircraft was flying at—we assumed about 450 knots,” said Mr McLaughlin. “We can’t know when the fuel actually ran out, we can’t know whether the plane plunged or glided, and we can’t know whether the plane at the end of the time in the air was flying more slowly because it was on fumes.”

The analysis was passed on after it was peer reviewed by others in the UK air industry and Boeing, reported Sky News.

The cause of the crash remains a mystery.