Street art’s natural high in Cavite

Call them vandals, and they wouldn’t mind. In fact, they refer to themselves as “Cavity”—a play on Cavite province—for they regard themselves more as the streets’ dental caries.

Call them vandals, and they wouldn’t mind. In fact, they refer to themselves as “Cavity”—a play on Cavite province—for they regard themselves more as the streets’ dental caries.

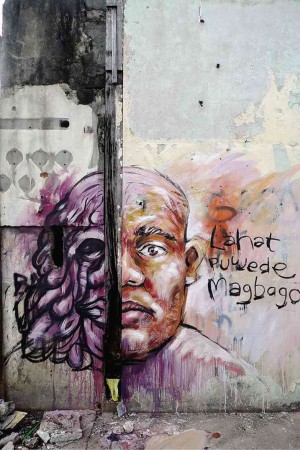

The subculture of street painting and graffiti carries no political undertones, no themes but purely visual expressions in public space.

“Like any visual art in a gallery, we know that ours is subject to criticisms. Yes, some people call it vandalism,” says Rai Cruz, a 28-year-old multimedia arts instructor at Mapua Institute of Technology in Manila.

Cruz is one of the founders of Cavity Collective, a “crew” (group) of Cavite-based street artists and graffiti writers. With him in the core are visual artists, who want themselves to be called Blic, 28, and Lamok Skito, 30, and 18 others.

“It was Blic’s idea that we paint together one day. He contacted us for a ‘sesh’ (session),” Cruz said.

Article continues after this advertisementThat was how Cavity started in 2010 and has since done over a hundred street art and graffiti works one could hardly miss on a building façade, an abandoned structure or a public footbridge in Cavite and Manila.

Article continues after this advertisementThe collective has 80 to 100 other members who are less active and part of what they called the Cavity Community.

Cavity does “commissioned” works, too, in Laguna and in as far as Pangasinan, Iloilo and Davao.

A thin line separates street artists and graffiti writers, Cruz said. The artists use paintbrush while the writers are masters of the spray paint. After all, graffiti is also a form of “calligraphy,” a stylized way of painting a person’s name, he said.

What brings the two together? “Both are done where it is visible to the largest crowd possible,” Cruz said. “It’s like reclaiming an urban space. It’s communicating.”

‘Work-picture-go’

What they do and what they get out of it, many do not understand.

“There’s a natural high,” says Lamok, who dreams of painting the stretch of Edsa to be seen by thousands of commuters every day.

Cruz said that as much as possible, the group asks for permission to paint façades, especially of privately owned structures.

But some walls are just too elusive. “So we’ve learned to come up with stories like it’s a school project, or that it’s part of community service,” Cruz said.

“Sometimes, we say we’re joining an art competition or that we wanted their wall featured in a magazine,” he said.

What if none of those worked? They resort to “bombing,” which sometimes ends up in a shouting match with the building owners or being accosted by village patrolmen.

“Vandalism or bombing is another subject. We do that but don’t often talk about it,” says Juanito “Quiccs” Maiquez, 32.

Maiquez, a toy designer, is a member of another crew, Pilipinas Street Plan, but also joins Cavity’s sesh. It’s like part of an artist’s “vanity” to leave his mark all over, he said.

“Work-picture-go, that’s it. We don’t mind if they repaint it. Anyway that’s the sense (of a public space), it’s free for all,” he said.

As part of a loose code of ethics, graffiti writers and street artists do not paint over fresh work.

Cruz explains a “tag” as a simple scribble on the wall, the “throw-up” or those measuring 4- to 5-foot tall, and the “piece” for the larger one. “You never tag over a piece,” he said, a rule that only they can understand.

Reception

Usually, it takes two hours to finish a “piece” and sometimes days, depending on the design.

“There’s always the risk that either someone paints over it or the structure later gets torn down. So we know (the artwork) is just temporary,” Cruz said.

But what they try to preserve is that very “moment” that they take a photograph of a finished job. What is also more important is for people to see and start thinking.

“We hope to prompt questions like ‘what those drawings are’ or for to make people wonder ‘how in the world did they get to paint that side of a bridge,” Cruz said.

If the public is not totally receptive yet, Cruz believed that street art had drawn more public awareness. He thought about an instance when an armed policeman approached him, only to inquire about the spray paint for he was also into graffiti.

Another instance was a sesh near a private bank.

“The security guard tried to drive us away when in fact the wall was no longer part of bank property,” Cruz said. “The people in the community started coming out to tell us: ‘Go ahead, paint that wall.’”