Ancestral land titles shake up Baguio

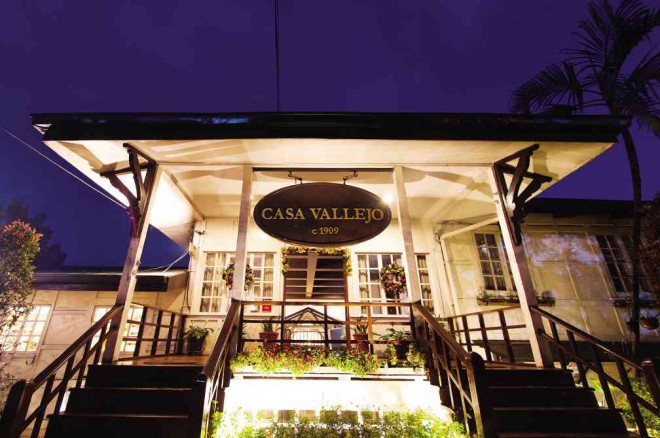

THE GOVERNMENT land on where Casa Vallejo, Baguio City’s oldest hotel, stands is being claimed by a family holding an ancestral land title. RICHARD BALONGLONG

No matter what generation he or she belongs, the average Filipino will always associate the summer capital with cool mountain air, pine trees and the indigenous Filipino.

So a tiff between the city and its Ibaloi community over who has proper land rights in American government-built Baguio City would ordinarily be dismissed as an absurd tale. But the truth is indeed far stranger than fiction.

Since 2010, the Baguio government and various national government agencies have been vocal about their objections to ancestral land titles issued to Ibaloi clans by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

The applicability of the Certificates of Ancestral Land Title (CALT) in Baguio has been a contentious issue since the passage of Republic Act No. 8371 (Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 or Ipra) because Section 78 of the law excludes the Baguio townsite reservation from Ipra coverage, except for land claims recognized in the early part of the 20th century by the American colonial government.

Baguio asserted Section 78 when NCIP issued the CALT to Ibaloi families in 2010, many of which cover parks, watersheds and even a portion of the presidential mansion. The Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) had gone to court to either restrain these titles or to seek their nullification, on behalf of the city government.

Last week, however, the dispute escalated when one of NCIP’s adjudication offices granted the descendants of Kapitan Piraso, a Baguio Ibaloi pioneer, permission to take possession of the city’s oldest hotel, Casa Vallejo, which is inside their CALT coverage.

Eviction notice

Felix Mariñas Jr., president of the Natural Resources Development Corp. (NRDC), sent security personnel to protect the 104-year-old Casa Vallejo from being acquired by the heirs of Cosen Piraso, using a writ of possession granted by the NCIP regional hearing office in November last year. Casa Vallejo is under the custody of the NRDC, the corporate arm of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

The city sheriff served the operator of Casa Vallejo a notice to vacate the premises by Jan. 10 on behalf of the Ibaloi family, Mariñas said, so he declared at a gathering of Baguio’s prominent families last week that the state firm would not heed the writ. He said the document was processed without NRDC’s knowledge.

Casa Vallejo, located on Upper Session Road in the central business district, used to be home to government employees during the years when the American colonial government had developed and populated Baguio from 1909 to 1923, before it was operated as a hotel by Salvador Vallejo, a Spaniard, and his descendants until 2000. Casa Vallejo’s plight quickly generated a change.org online petition mounted by Baguio residents to save the historic hotel.

The writ of possession over a government lot affecting Casa Vallejo is the first to be granted to an indigenous peoples family, the DENR said, although Baguio has been besieged by contentious land disputes involving ancestral land claims for decades now.

Mariñas said the dispute was instigated by a government agency that failed to follow its own rules, so it would take the national government to correct the agency’s mistakes.

On Tuesday, the issue was resolved by the NCIP itself. The commissioners suspended the writ and all matters pertaining to the CALT threatening Casa Vallejo, Mariñas said, giving the government time to discuss the problem the CALT had created.

“It would have been embarrassing for the government had one of its agencies allowed a family to take possession of a government lot,” he said.

Other Ibaloi families have joined the government’s fight and have gone to court to contest the CALT issued to dubious claims, said Judith Maranes, a Baguio Ibaloi leader.

Maranes said many Ibaloi families do not want the false claims to tarnish Ipra, a law that may finally grant them justice for historic wrongs.

Original settlers

A December 2002 study conducted by the Ibaloi claimants indicated that there are 757 legitimate ancestral land claims in Baguio. These claims are backed by comprehensive historical accounts, validated family trees and scholarly researches, said Maranes, who took part in the study.

The study makes the case that Baguio’s original settlers were the Ibaloi. Baguio used to be one of 31 rancheria (settlements) in Benguet.

However, “some native inhabitants were actually dispossessed of their lands,” when the American colonial government developed Baguio, it said, and most claims now fall within watersheds and government reservations.

Loopholes

For example, there are eight claims over lands within the Philippine Military Academy compound, according to the study. There are 192 ancestral land claims over the various villages inside the Camp John Hay reservation and 20 claims over lands within the Busol watershed in the northern section of the city.

The CALT issue also disturbed many residents because of allegations that IPs have been selling their ancestral lands, so some Baguio officials have offered to fix these loopholes.

In a proposed resolution last year, Councilor Isabelo Cosalan Jr., an Ibaloi, suggested that Ipra be amended so it would stipulate a 10-year prohibition on the sale or transfer of all CALT to give the city government time to secure lands it would need to preserve, particularly in government reservations and inalienable lands.

Maranes said the IPs should not be cast as villains in the dispute that described the Ibaloi as land grabbers or destroyers of the Baguio environment.

After all, Baguio played a role in Ipra’s passage.

The city’s universities nurtured the crusade to recognize indigenous peoples rights during martial rule, an assertion made by diverse groups like the Bibak (the group’s acronym stood for Benguet, Ifugao, Bontoc, Apayao and Kalinga) of the 1970s and 1980s, the activist Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) and slain rebel priest Conrado Balweg.

After the 1986 EDSA Revolt, one of President Corazon Aquino’s first tasks was to make peace with Balweg and form the Cordillera Administrative Region. The 1987 Constitution recognized ancestral land rights for the first time, following extensive lobbying from Baguio scholars, indigenous rights advocates and Ibaloi residents. Ipra soon followed in 1997 and it became a mechanism to enforce the indigenous peoples’ constitutional rights.

Native land rights

In a speech during the 104th Baguio charter anniversary celebration on Sept. 1 last year, Supreme Court Associate Justice Marvic Leonen said Ipra was part of a “small march of doctrines” benefiting indigenous Filipinos since the late United States Supreme Court Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes recognized the concept of native land rights over what is now Camp John Hay in 1909.

Before he became a member of the high court, Leonen, a Baguio native, defended Ipra in the Supreme Court when it heard oral arguments on the law’s constitutionality, following a lawsuit filed by the mining industry.

“The gods may have intervened [when the high court voted on the constitutionality of Ipra] to say that we should give a chance to those who are indigenous to actually own lands that they owned since time immemorial,” Leonen said.

“As concerned citizens, we urgently seek protection for Casa Vallejo as it is currently the subject of a property dispute. We fear that the outcomes of this dispute may lead to the destruction of an important heritage site.

“The legal possession of the property is a complex issue, but with the recognition of Casa Vallejo as an important cultural property, we hope to at least protect it from any future demolition and to preserve it as part of Baguio’s heritage. Regardless of ownership of the property, it is in the interest of Baguio City that it is not demolished.”

Excerpts from a petition to declare Casa Vallejo a heritage site and ensure its future protection and preservation.