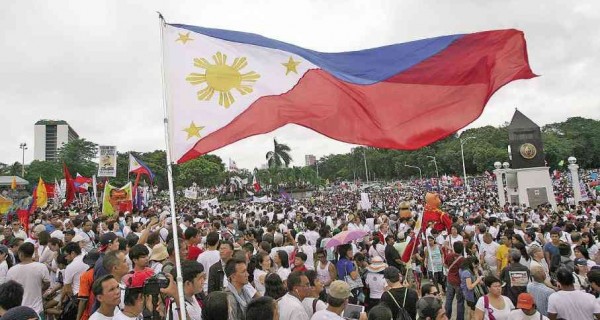

AQUINO’S BOSSES AGAINST PORK From all walks of life, Filipinos, including children, came in droves to Rizal Park in Manila to take part in the Million People March to protest the misuse of the multibillion-peso pork barrel of lawmakers and to call for the pork’s abolition. MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

MANILA, Philippines—It was a tumultuous year marked by the pork barrel scandal, the siege by secessionist rebels and a devastating supertyphoon, but 2013 was also a breakout year for Filipinos who said “No” to corruption, former National Treasurer Leonor Briones said on Thursday.

Thanks to whistle-blowers, Janet Lim-Napoles’ alleged racket of converting P10-billion pork barrel into kickbacks through dummy foundations, forged signatures of officials, and strong under-the-table political connections came to light.

It was so scandalous that thousands across the country took to the streets to protest the large-scale misuse of taxpayers’ money, and President Aquino eventually announced it was about time the pork barrel system was abolished.

Some were ready to sweep the scandal under the rug, arguing that the annual pork barrel allocations of 24 senators and close to 300 congressmen constituted only 1 percent of the budget, but the citizens were not, said Briones, a professor at the University of the Philippines’ National College of Public Administration and Governance.

“The money is being squeezed from (the public), so naturally their reaction is very strong,” she said by phone.

If the massive protests and strident calls for the abolition of the pork barrel proved anything, she said it was this: “We’re getting back to our senses. It’s not enough to accept things as they are. We can demand change.”

The protests had been fanned by an Inquirer investigative report and a subsequent report by state auditors on the misuse of the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF), the official name of the legislative pork barrel.

Eventually, a complaint for plunder was filed against Napoles, Senators Jinggoy Estrada, Ramon Revilla Jr. and Juan Ponce Enrile and 34 others before the Office of the Ombudsman over the scam.

Former Sen. Aquilino Pimentel Jr. acknowledged that the removal of lawmakers’ discretion in identifying projects would redound to the good of the country.

But he aired reservations on the abolition of the pork barrel, arguing that most lawmakers allotted it for scholarships and medical assistance for their indigent constituents.

“Anything that results in reaching the level of political service to the people is good even if in the process people may have to pay the price,” he said by phone Wednesday.

Otherwise, the pork barrel system was “good” as long as the money “wasn’t stolen and didn’t go into the wrong hands,” Pimentel argued.

Close on the heels of the pork barrel scandal, another controversy, this time about the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP), broke out.

In a privilege speech in September, Estrada ranted about being singled out in the pork scam, but opened another can of worms when he disclosed that senators, including himself, were allotted an additional P50-million pork barrel after the Senate convicted Chief Justice Renato Corona in May 2012.

It turned out three of his colleagues got a bigger allocation for their pet projects. Franklin Drilon got an allocation of P100 million; Francis Escudero, P99 million, and Enrile, P92 million.

Pressed for details, Budget Secretary Florencio Abad admitted 20 senators received additional pork barrel allotments amounting to P1.107 billion after Corona’s trial and that the fund was sourced from DAP.

He said the DAP mobilized pooled savings and was a mechanism introduced in 2011 to stimulate government projects—including projects chosen by lawmakers.

Constitutional and legal experts, however, argued that the releases from DAP were unconstitutional because this “new animal” was never mentioned in the General Appropriations Act.

The President defended it, saying only 9 percent of DAP releases in 2011 and 2012 went to projects suggested by legislators.

Observed Briones: Suddenly, the executive department and Congress swapped roles—the President and the Cabinet officials were the ones who “allocated” money while the lawmakers “implemented” projects.

“In the case of the DAP, it’s not even in the General Appropriation Act. There’s no constitutional basis. You can’t spend it without a corresponding appropriation. The DAP has no appropriation,” Briones said, adding that DAP, like the PDAF, should be struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

In November, the Supreme Court justices voted 14-0 to declare the 2013 PDAF as unconstitutional. The high court nullified all legal provisions of past and present congressional pork barrel laws. The court has set oral arguments for DAP on Jan. 28.

Pimentel, head of the Center for Local Governance at the Makati University, said the public was the biggest gainer from the DAP controversy.

“Because of what happened, officials are becoming more conscious of the need to abide by higher standards than before,” he said.

The government needs to mobilize more funds to respond to rehabilitation requirements in calamity-hit areas of the country.