Cavite town looks beyond dark page in history

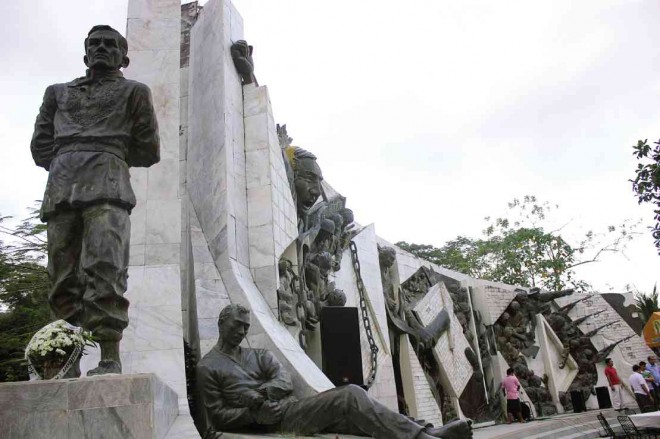

THE TOWERING Bonifacio statue and the relief wall of the Katipunan, the revolutionary movement founded by Andres Bonifacio to topple Spanish rule preserves history at the hero’s execution site in Maragondon, Cavite. The local government hopes to rehabilitate the three-hectare site into an ecotourism site. SOUTHERN TAGALOG EXPOSURE/CONTRIBUTOR

Maragondon, where mountains cast shadows over vast greenery and animal-drawn carts carrying bamboo poles cause village traffic, is counting on a dark detail in history to turn the tide and spur economic activity.

A major event on Nov. 30, commemorating the 150th birth anniversary of revolutionary hero Andres Bonifacio, can be the start of it all, says the Cavite town’s mayor, Reynaldo Rillo.

Little-known to many, it was in Mt. Nagpatong in Maragondon’s Barangay (village) Pinagsanhan-B, where Bonifacio and his brother Procopio, were killed on May 10, 1897.

People often confuse the execution site with an adjacent peak, Mt. Buntis, until the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), formerly the National Historical Institute, declared it a memorial shrine in 1979.

Sometime in 2004, the municipal government erected a 12-foot bronze statue of Bonifacio and his brother, a marble wall relief with a swimming pool on the side, turning the three-hectare land into a potential hiking and camping destination.

Despite earlier efforts to attain progress by its local officials, Maragondon, about an hour’s drive by car from Manila, has remained a third-class municipality (annual income: P35 million-P45 million) dependent on a bamboo industry.

Rillo, who formally assumed the mayoral post in July, says only about 5,000, mostly students, have visited the shrine of the Katipunan founder.

“The Aguinaldo shrine (in Kawit town, also in Cavite) was made so beautiful, the government seemed to have neglected the Bonifacio shrine,” says Andriane Ng, spokesperson of the militant Bagong Alyansang Makabayan (Bayan)-Southern Tagalog. The group helped organize the Nov. 30 commemoration event.

Crispin Gonzales, a driver and resident of Maragondon, says he has never gone to the shrine, 5 kilometers from the town proper, for fear that his tricycle will not survive the rough road.

There is no public transportation to reach the place or electricity, and communication signal is poor.

To mountaineer Christopher Ayeras, 27, who was passing by on his way to Mt. Buntis, the Bonifacio event can help promote the site—an off the beaten track for hikers.

Local pride

Bonifacio’s arrest and execution, on orders of fellow Katipunan leader Emilio Aguinaldo, remain a sensitive issue among historians and political factions in Cavite, says NHCP Commissioner Rene Escalante, a guest during the Nov. 30 program.

Escalante describes the story as “embarrassing” and “nakakikilabot” (hair-raising) as it is not being talked about “because the people behind it were (Bonifacio’s) fellow Filipinos and members of the organization that he himself founded.”

Despite this grim detail and the scanty public attention, municipal tourism officer Louie Lagac says the residents are not at all ashamed of history and its implications on the town.

“We are actually proud because even if it took place here, those people (who executed Bonifacio) were not from Maragondon,” he says.

In fact, he adds, three of the six-member court martial who were from Maragondon “were the only ones who refused to carry out the execution” of the Bonifacio brothers.

Rillo says the municipality is seeking P150 million support from the national government to rehabilitate and promote the shrine.

Bayan has started its own fund drive to help improve the roads leading to the site.

With the NHCP’s call to move past politics surrounding the dark episode, Rillo says he wishes to offer tourists a “beautiful place” to relax and learn more of the past.