China aims to curb wrongful convictions amid abuse

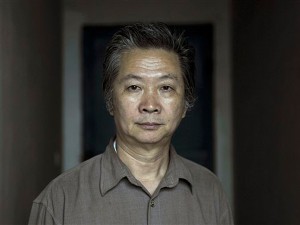

Chen Keyun poses for a picture in this May 4 file photo at his home a day after the Fujian Provincial Higher People’s Court acquitted him of guilt in the 2001 bombing of a Communist Party office in Fuqing city in southeast China’s Fujian province. AP

BEIJING, China—Chen Keyun’s legal nightmare began in 2001 when he was accused of detonating a bomb outside a Communist Party office in his southern coastal city of Fuqing.

Chen denied committing the crime but was held for 12 years, during which he was tortured into confession and twice sentenced to death. He finally was released and exonerated this year, a case that exemplifies the miscarriage of justice that China’s Supreme People’s Court now says it wants to curtail.

Last week, it released its first set of detailed recommendations for preventing wrongful convictions, judges should presume defendants are innocent until proven guilty, reject evidence obtained through torture, starvation or sleep deprivation and refrain from colluding with police and prosecutors.

The moves reflect Chinese leaders’ recognition that an increasingly prosperous public is demanding a more predictable and fair justice system, though party officials are unlikely to fully loosen their grasp over the courts.

“It is of significance and if adopted seriously, it will effectively help prevent the occurrence of wrongful convictions,” said Prof. Tong Zhiwei, a legal expert at the East China Politics and Law University in Shanghai. “The question is whether the regulation will be fully implemented at local levels.”

Article continues after this advertisementThe recommendations are seen more as an effort to build a more professional judiciary, one in which judges observe legal process and make rulings that are based on sound evidence—rather than grant courts full independence.

Article continues after this advertisement“If courts can be more independent, then these problems can be easily solved,” said Li Fangping, a prominent defense attorney in Beijing. “This guidance can only increase their independence a little bit. On technical issues, it will be of help, but as long as there are cases where there will be intervention, it won’t be of much use.”

In China, the party controls the courts, police and prosecutors. Some judges are not trained in law, and they rarely acquit defendants for fear of embarrassing their partners in law enforcement. Experts and defense lawyers say police commonly fabricate evidence or use torture to obtain confessions.

Chen Keyun was a manager of a state-owned labor recruiter in Fuqing when a bomb exploded in 2001 outside the city branch of the party agency that investigates cadres for corruption. The explosion killed an agency driver.

Attacks on offices that represent party or government power in China are treated with great urgency, with authorities moving swiftly to solve the case and punish perpetrators to send a message of zero tolerance.

Police turned to Chen as a suspect because he previously had been investigated by the anti-graft office and punished. Five others, including Chen’s driver Wu Changlong, Chen’s wife, Wu’s former brother-in-law and two migrant workers, also were arrested for involvement in the attack.

Police detained Chen, then 48, and in the two months that followed, he said, deprived him of sleep, beat him, starved him, and dangled him for hours by strapping his wrists to iron rods on a high window.

“They treated me like less than a dog,” Chen, now 60, said in a phone interview. “I was an old Communist Party cadre who had been about to retire, I had never thought that something like this could happen to me.”

Chen said he protested his innocence until he could no longer endure the torment.

His interrogators eventually forced him to sign a confession, though he later tried to retract it, telling other investigators he had been tortured. Chen’s lawyer took pictures months later showing deep welts on his wrists. Others accused in the case also said they were tortured.

The Fuzhou City Intermediate Court sentenced Chen and Wu to death with a two-year reprieve in 2004, and three of the others to various terms of imprisonment. The defendants appealed in 2005 and several domestic newspapers reported that they might have been wrongfully convicted. The Fujian provincial high court turned the case back to the city court and ordered a retrial.

In 2006, the Fuzhou court tried the case again and upheld the suspended death sentences for Chen and Wu. They appealed again, and in 2011 the provincial court tried the case yet again. In May, the court acquitted all five defendants.

The court offered compensation of about 4.2 million yuan ($690,000) to the five of them in September but they are demanding more, as well as an acknowledgement that they were tortured.

Chen’s is one of a few high-profile cases of wrongful convictions overturned in recent months. In March, a court in eastern Zhejiang province retried and acquitted two men who were convicted in 2004 of raping and murdering a woman, after DNA evidence from another case ruled out their involvement in the crime.

The Supreme People’s Court’s latest directive is seen as building on earlier comments by its president, Zhou Qiang, on the importance of preventing wrongful convictions. Rights activists say it is a welcome move, but may not be enough to curb abuses.

“The guidelines fail to address the structural problems that create wrongful convictions—police power that goes unsupervised, the lack of judicial independence, the absence of effective remedies when things go wrong, and weak defense rights,” said Maya Wang, a Human Rights Watch researcher in Hong Kong. “Thus it will be unlikely to achieve much impact on the ground.”