WASHINGTON — The discovery of a previously unknown wooden structure at the Buddha’s birthplace suggests the sage might have lived in the 6th century BC, two centuries earlier than thought, archaeologists said Monday.

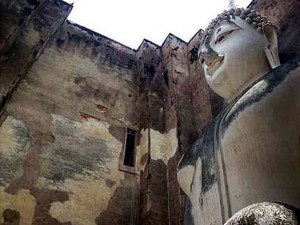

Traces of what appears to have been an ancient timber shrine was found under a brick temple that is itself within Buddhism’s sacred Maya Devi Temple at Lumbini, in southern Nepal near the Indian border.

In design it resembles the Asokan temple erected on top of it. Significantly, however, it features an open area, unprotected from the elements, from which it seems a tree once grew — possibly the tree where the Buddha was born.

“This sheds light on a very very long debate” over when the Buddha was born and, in turn, when the faith that grew out of his teachings took root, said archaeologist Robin Coningham in a conference call.

It’s widely accepted that the Buddha was born beneath a hardwood sal tree at Lumbini as his mother Queen Maya Devi, the wife of a clan chief, was traveling to her father’s kingdom to give birth.

But much of what is known about his life and time has its origins in oral tradition — with little scientific evidence to sort out fact from myth.

Many scholars contend that the Buddha — who renounced material wealth to embrace and preach a life of enlightenment — lived and taught in the 4th century BC, dying at around the age of 80.

“What our work has demonstrated is that we have this shrine (at Buddha’s birthplace) established in the 6th century BC” that supports the hypothesis that the Buddha might have lived and taught in that earlier era, Coningham said.

Radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence techniques were used to date fragments of charcoal and grains of sand found at the site.

Geoarcheological research meanwhile confirmed the existence of tree roots within the temple’s central open area.

Coningham co-directed an international team of archeologists at Lumbini that was funded in part by the Washington-based National Geographic Society, which plans to telecast a documentary, “Buried Secrets of the Buddha,” worldwide in February.

The team’s peer-reviewed findings appear in the December issue of the journal Antiquity, ahead of the 17th congress of the International Association of Buddhist Studies in Vienna in August next year.

Lumbini — overgrown by jungle before its rediscovery in 1896 — is today a UNESCO world heritage site, visited by millions of pilgrims every year. Worldwide, Buddhism counts 500 million followers.

In a statement, UNESCO director general Irina Bokova called for “more archeological research, intensified conservation work and strengthened site management” at Lumbini as it attracts growing numbers of visitors.

UNESCO and the Nepalese government had invited Coningham, Britain’s leading South Asian archaeologist, to join Nepal’s former director general Kosh Prasad Acharya to steer the Lumbini effort.

Since it’s a working temple, the archaeologists found themselves digging in the midst of meditating monks, nuns and pilgrims.

It’s not unusual in history for adherents of one faith to have built a place of worship atop the ruins of a venue connected with another religion.

But what makes Lumbini special, Coningham said, is how the design of the wooden shrine resembles that of the multiple structures built over it over time.

Equally significant is what the archaeologists did not find: signs of any dramatic change in which the site has been used over the ages.

“This is one of those rare occasions when belief, tradition, archaeology and science actually come together,” he said.