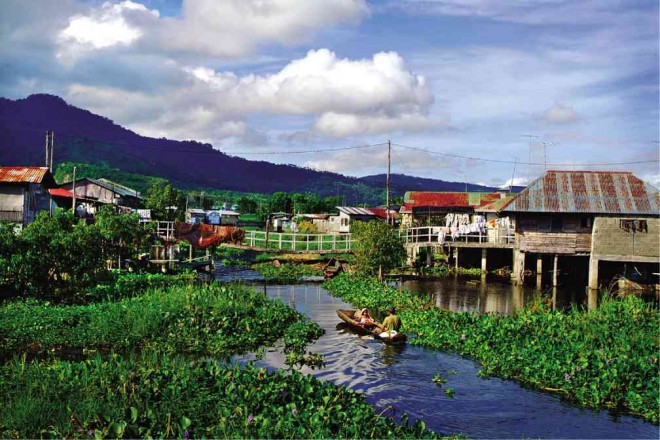

THE FISHING village of Tadlac in Los Baños, Laguna, is among the many communities around Mt. Makiling that enjoy the bounty offered by the mountain, including its forest with more than 2,000 species of endemic plants, its geothermal energy and its groundwater. AL BENAVENTE / CONTRIBUTOR

Only a handful of rangers look after a 4,244-hectare tropical rainforest teeming with plant species. Equally pitiful is the annual budget of P800,000 to operate and maintain a primary forestry training laboratory.

Now, park managers at the Mt. Makiling Forest Reserve see a glimmer of hope after Mount Makiling was declared an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) Heritage Park recently, the fifth in the Philippines and the 33rd in the Southeast Asian region.

The recognition, although without any monetary grant, “gives us leverage to seek more support and change policies,” said Dr. Nathaniel Bantayan, director of the Makiling Center for Mountain Ecosystems (MCME).

It is about time, he said, “that Makiling graduates from mendicancy.”

The Makiling Forest Reserve (MFR), 65 kilometers south of Manila, was established in 1910. Management and control of the forest had been transferred to different state agencies five times, and its name changed three times until 1990 when jurisdiction of the MFR was fully given to the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB), through the MCME.

Since then, scientists and researchers from around the globe have flocked to Makiling to study the 2,057 species and subspecies of mostly endemic plants.

The inactive volcano sits on a vast source of geothermal energy fed to the national grid, and fresh water that the entire forest had to be topographically divided into four subwatershed zones.

Aside from the water supplied to communities and industries, farm workers benefit from the forest products and raw materials. A study by MCME showed that at least 2,000 people were directly dependent on the Makiling forest.

Agricultural lands also owe its fertile earth to the rich soil that naturally erodes from the mountain.

“But the [stakeholders] do not realize that they are able to operate because there’s a good forest up there (in Makiling),” Bantayan said, noting that surrounding private businesses have not shared their resources to maintain the forest reserve.

He raised issues concerning land-use plan and territorial boundaries since the MFR straddles four municipalities belonging to two provinces.

“Local governments units tend to focus only on the part of their territory that generates income when their land-use plans should encompass the watershed areas,” Bantayan said.

‘Sleeping giant’

What is needed is a “change of mindset” of local government and industry leaders, he said.

“It should no longer be the case wherein we have a wish list and we ask each of them what they might want to give,” he said. “Help should come from them and form part of their consciousness.”

Asean Center for Biodiversity director Roberto Oliva has offered the agency’s support to the UPLB in preparing its master plan as Makiling becomes a national ecotourism site.

“We are looking at a next big attraction,” said Oliva of the MFR, which he likened to a “sleeping giant” because of its big potential to draw not only the scientists and researchers but tourists and hikers as well.

“Let’s protect the biodiversity and at the same time invite people to see it,” Oliva said, to which Bantayan pointed out that it should not be the responsibility of a single agency, “but everyone’s role.”