Baguio doc leaves behind proofs of kindness

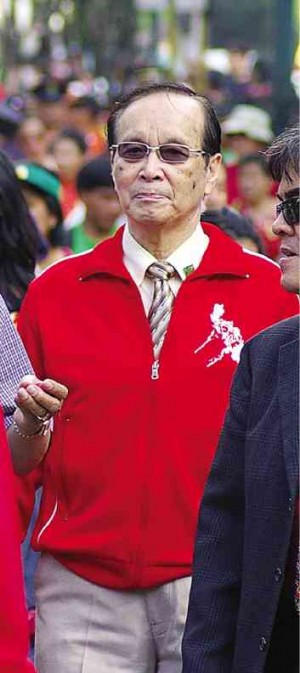

DR. CHARLES CHENG during the celebration of Lunar New Year in Baguio in 2012. RICHARD BALONGLONG/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

BAGUIO CITY—A poor boy from the remote village of Patiakan in Quirino town in Ilocos Sur province said he owed his life to Dr. Charles Cheng.

“Without the medicines he gave me for free, I would have not been cured of TB (tuberculosis),” said the boy, who sought the doctor’s help while he was a college student in the 1970s at a university in Baguio City. “Had I not been cured I would not be where I am now.”

That once barefoot, poor boy from Patiakan is now Baguio City Mayor Mauricio Domogan, who also served as representative of the city for three terms in Congress.

Domogan is just one of many people who have fond memories of Cheng, 81, who died of dengue and organ complications on Sept. 28.

Katherine, the wife of Cheng, said she was so touched by Domogan’s insistence to give her some money despite her refusal when the doctor was confined for more than a month at a private hospital here.

“I practically owe my life to Dr. Cheng,” Domogan told Katherine.

Many poor patients the doctor had helped have similar accounts.

Some of them wonder why Cheng, for decades, had opted to maintain a clinic at an old, unassuming, almost dilapidated building on Lapu-Lapu Street, one of the back streets of Magsaysay Avenue in the central business district.

The clinic was also strategically located for the benefit of his poor patients. Since it is near a bus terminal, poor patients from the vegetable district of the provinces of Benguet and Mt. Province could easily catch a bus back home after a consultation, Cheng said in an earlier interview.

After obtaining his Doctor of Medicine and Surgery degree from the University of Santo Tomas, Cheng opted to stay and devoted a big part of his life serving poor indigenous folk.

Despite his busy schedule as medical director of the Baguio Filipino-Chinese General Hospital, he would schedule medical missions in remote communities of Benguet and Mt. Province.

He made himself available for lectures and forums even in remote communities on various topics affecting people’s health. He would speak about the hazards of pesticides to humans and the environment, iodine deficiency and mental health, cancer, acupuncture, herbal medicines and sports medicine.

That he was also engaged in medical research gave him authority to speak strongly about certain medical and health concerns. For example, Cheng and his wife were the first to study the adverse health impact of pesticides and fungicides in Benguet.

Their 1994 book, “Pesticides: Hazardous Effects on Benguet Farmers and the Environment,” sounded the alarm of the deadly impact of farmers’ obsession with pesticides.

Apart from medicine and health, Cheng was also passionate about history. He agreed with the view that Philippine history, much of which was written by the country’s colonizers, remains incomplete and much of it has to be corrected.

That’s why he would encourage local writers and scholars to interview elders and document their accounts about the local community’s past before these are forgotten.