Before martial law was a bridge tragedy

The imposition of martial rule by then strongman Ferdinand Marcos 41 years ago came on the heels of a tragic event during the Peñafrancia fiesta celebration in Naga City in September 1972.

More than a hundred devotees were killed when the Colgante Bridge in Barangay Peñafrancia collapsed from the weight of spectators waiting for the pagoda of Bicol’s patroness to pass halfway to its destination during the fluvial procession along the Naga River on Sept. 16, 1972, a Saturday.

The procession was bringing back the image of Nuestra Señora de Peñafrancia to her shrine from Naga Metropolitan Cathedral after the novena.

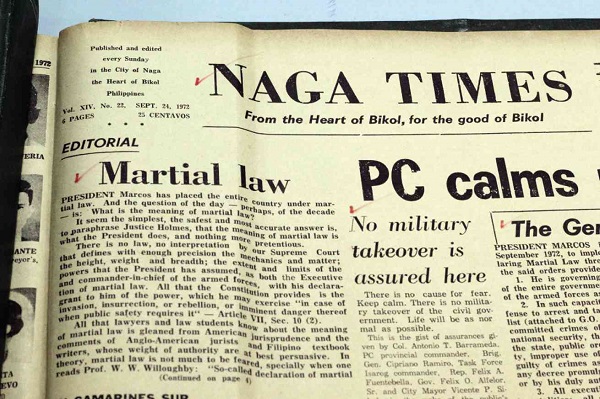

Naga, the “Heart of Bikol” situated 382 kilometers south of Manila, was then simmering with rumors of a supposed meeting of New People’s Army (NPA) leaders with Jose Maria Sison, secretary general of the Communist Party of the Philippines. This was splashed on the frontpage of the local weekly newspaper Naga Times on its Sept. 17 issue.

NPA top brass

The article retold the intelligence report of the Philippine Constabulary (PC), forerunner of Integrated National Police and now Philippine National Police. Details of the supposed meeting of Sison and Marco Baduria, founder of the Bagong Katipunan movement in Camarines Sur, were in the story.

“Kumander Diego was reported to be in this city the other day to coordinate in the projected caucus of ranking NPA chieftains of Bicol,” lawyer Luis General Jr., Naga Times editor in chief, narrated in the article “PC Report: NPA top brass meet here.”

The intelligence report from the PC provincial command was received by Naga Times on Sept. 15, 1972, a day before the supposed meeting.

The story also claimed that a meeting of NPA commanders took place on Sept. 7 in the hacienda of Antonio Amoranto in Sitio Burobamban, Barrio Tinawagan in Tigaon town. The rebel leaders were identified only as Jing, George, Cuatro, Dindo, Gimo, Ka Andy and Ka Mamo/Larra, who were with three “NPA amazons.”

They took up the proposal of Ka Andy to stage an ambush of government troops in retaliation for the killing of seven communist rebels by Task Force Isarog commandos in Sitio Pulang Bagting, Barrio Coyaoyao, in Tigaon on Aug. 29.

According to the story, the ambush plan was shelved because Ka Larra had convinced the group to bid for time for lack of high-powered weapons. Ka Larra distributed bullets for a .22 cal. revolver and assorted medicines.

The meeting purportedly occurred on Sept. 16, which was also when the fluvial procession was bringing back the image of Ina to the shrine. But the gaiety that usually accompanied the transfer turned into tragedy. A total of 111 people died when Colgante, an old bailey bridge, fell.

This was in the account of Naga Times on its Sept. 24, 1972 issue. It was to be its last issue after martial law was declared on Sept. 21, 1972.

Colgante aftermath

In the aftermath of the tragic event, Congressman Felix Fuentebella (father of former Deputy Speaker Arnulfo Fuentebella and grandfather of incumbent Camarines Sur Rep. William Felix “Wimpy” Fuentebella) announced the release of P400,000 for the construction of a permanent span across the accident site, according to Naga Times.

In Congress, it said some P3,000 in cash and pledges were initially collected after Fuentebella and Ramon Felipe Jr. started passing the hat for the victims’ families.

Bicolano Bishop Jesus Varela, who was assigned to Ozamiz City before his final assignment and retirement in Sorsogon, sent his condolence while appealing for “more civic consciousness and cooperation” in taking all measures to avoid a similar tragedy, the paper said.

Naga Times columnist Choleng Hidalgo, in her column “My Two Cents’ Worth,” stressed that the bridge collapsed due to the blatant disregard of the imminent danger that lurked on it.

“Similarly, the devotees who flocked to the bridge and those who perished in the accident should have foreseen the danger of the moment,” she said.

Hidalgo cited one Vic Flores, a radio reporter who, she said, kept on warning people of the danger before he himself fell into the water with the other victims.

But it was as if things would not get better that day. On the same day, 53 inmates bolted the provincial jail. A week later, seven of them were killed, six were captured, and 15 surrendered.

Lawyer Henry Briguera, a retired broadcaster and columnist of the weekly Bicol Mail, vividly remembers how martial law descended on the city almost unnoticed with the pall of grief hovering the place.

“I was among the local mediamen who, as per terminology of the late Col. Antonio “Tony” Barrameda, the then PC provincial commander in Camarines Sur, were placed under the ‘protective custody’ of the military,” Briguera recounted.

They were busy raising funds for the victims when Marcos declared martial rule, he said. “The news did not immediately catch the attention of the Bicolanos, particularly the broadcasters, because of the Colgante Bridge tragedy.”

Briguera was detained on Sept. 26, 1972, in Camp Canuto in the neighboring town of Pili, along with Naga Times editor in chief General and several other journalists whom he identified as lawyer Antonio Carpio, Ramon Brillantes, Leon S. Palmiano Jr., Ely Compuesto and Nonong Triviño.

But none of them suffered maltreatment while under the “protective custody” of the military for over a month. The archbishop of Caceres, Teofisto Alberto, interceded and requested the authorities to release some of Briguera’s companions.

Briguera said only radio station dzGE, which was owned by Filipinas Broadcasting Network, was allowed to air while all the local newspapers were closed, except for one who was “to serve as propaganda tool of the dictatorship.”