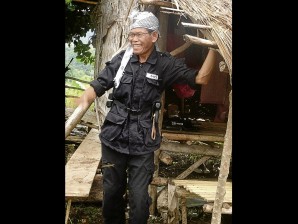

RENEGADE Moro rebel leader Ustadz Ameril Umra Kato bids journalists goodbye after an hourlong interview in his mountain lair. RYAN ROSAURO

Amid fears of a shaping splinter group within the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) out to wage its own war for Bangsamoro independence, there is curious public attention on what is really on the mind of its purported leader, Ameril Umra Kato.

At the outset of an interview on Aug. 16 in his Maguindanao mountain lair, Kato, the 65-year-old Saudi-trained Muslim cleric gave the impression of being a nascent Moro independence leader.

“How can you have independence for the Bangsamoro under the Philippine Constitution?” he stressed. “We are only claiming our right.”

Kato criticized MILF chief Murad Ebrahim for meeting President Aquino in Tokyo, saying this was a signal that the rebel leader was agreeing to craft its political demands under the Philippine Constitution, and therefore, a surrender of the group’s main aspiration.

“It cannot be achieved under (the political setup) of autonomy or federalism. Independence is the only goal,” he further said.

But after more than an hour of conversation, mostly in Filipino, Kato contradicted his own fierce assertions.

By his own revelations, he was really up to settle some score with the top MILF leadership over several decisions it made that affected him.

And to prove his accusation that the MILF Central Committee was wrong in the way it treated him, Kato wanted the “true account” of the yearlong war beginning July 2008 to come out.

Kato began setting up his own base in an area within the MILF’s Camp Omar in January after breaking away from the Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces (BIAF), the armed wing of the MILF.

By March, he publicly came out to announce the formation of the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF).

A year earlier, in December 2009, Kato resigned as commander of the BIAF’s 105th base command covering the strategic areas around the Liguasan Marsh that include towns in North Cotabato and Maguindanao.

The split has worried the government, apprehensive that Kato’s group would spoil the current ceasefire regime and make difficult the implementation of a resulting agreement in the already 14-year peace negotiations with the MILF.

Kato himself acknowledged that the MILF Central Committee had sent four missions to woo him back into its fold.

So far, he has stood firm on keeping his band—estimated to be between 100 and 200 men—supposedly to advance the vision espoused by the late MILF chair Salamat Hashim and already abandoned by the current leadership.

Ax to grind

Principal among Kato’s grudges was the issuance of a suspension of offensive military actions (Soma) by the BIAF in July 2009 as a reciprocal gesture to an earlier declaration by Malacañang of a suspension of military operations (Somo).

These declarations ended the yearlong war popularly attributed to the aborted signing of the landmark Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD).

Kato noted that the BIAF’s Soma was effective in all areas while the government’s Somo was selective, exempting his command and that of Abdullah “Commander Bravo” Macapaar and Aleem Ali Pangalian in Lanao del Norte.

This meant that his command would not be able to defend itself from government offensives.

Kato said he felt “left alone to be pursued relentlessly by government troops.” He further said his forces were inutile to defend their support communities from incursions of government soldiers.

In the wake of clashes in North Cotabato and Lanao del Norte, Macapaar, Pangalian and Kato were the subject of massive hunts. Both Macapaar and Kato carried P10 million reward money each, while Pangalian had P5 million.

Kato said the MILF leadership’s “abandonment” led to their being declared “lawless” by the government.

“Why rail against being pursued when you are a rebel? That is part of the life of a revolutionary,” said MILF chief peace negotiator Mohagher Iqbal, a 40-year veteran in the Moro rebellion.

“I have not cared about it. I have a price tag since 1977,” Iqbal added.

Kato’s other gripe is that he was not consulted when a Soma was hatched and eventually declared. “I was only able to know about such upcoming decision after I learned that my field commanders were made to sign a manifesto supporting a Soma issuance,” he pointed out.

Would he have supported such a move? “I cannot tell. It will depend on our discussions,” Kato said.

The immediate stop to offensive actions from both sides has been a clamor of civilian communities since the beginning of 2009 that culminated in a mass mobilization along the Cotabato-General Santos highway dubbed “Bakwit Power.”

But even as Kato acknowledged these frictions with the MILF leadership, he clarified that the recent skirmishes in Datu Piang town were not between the BIFF and the BIAF.

It was just incidental that those involved in the land dispute, which was the cause of the clashes, belong to either groups, he explained.

Independent probe

Kato lamented the tag of provocateur of the yearlong war that flared in August 2008. “Provoking war is difficult. We know that the government has strong armed forces,” he stressed.

“All of these accusations against me are lies,” he added.

Kato has urged the conduct of an independent probe by the International Monitoring Team (IMT) on the incidents “to set the record straight about who were really responsible (for starting the war).”

An internal probe of the MILF traces the string of events to an incident on July 1, 2008, in North Cotabato.

But Kato claimed that the provocation by Philippine Army and government militias dated back to April 2008.

“My troops were only coming to the aid of a colleague in Aleosan (North Cotabato) who was harassed,” Kato said as he explained the movement of BIAF troops under his command at that time.

Rising tensions were not contained and these snowballed into the large-scale attacks by August that was “wrongly attributed” to the aborted signing of the homeland deal, Kato related.

And what about the burning of houses in several North Cotabato villages?

“When the tensions flared up, Christians and Moros who have long been fighting over competing claims of land took advantage and used the moment as opportunity to hit on each other,” Kato explained.

“And because my troops were principally visible, all these actions were unfairly attributed to us,” he added.

An independent report prepared by the Mindanao Peoples Caucus about the BIFF, which was submitted to both the government and MILF peace panels, cited the failure of the IMT to undertake the probe of the alleged war atrocities in 2008.

An MILF official told the Inquirer that government forces had stopped pursuing Kato upon appeal of the MILF panel pending the result of an IMT probe. But the rebel did not specify when the manhunt was halted.

Acceptable form

Kato said that while he was maintaining a separate army, he was committed to the ideals of the MILF, which he said, was achieving liberation for the Bangsamoro people.

During the recent interview, Kato dropped using the word independence for liberation when asked to describe Salamat’s vision of Moro self-governance.

Instead, he explained that liberation must basically mean two elements: the establishment of Islamic governance and the freedom from political and economic control of the Philippine state.

“Even if it’s not the entire Mindanao and it’s not total independence or separation, so long as the two elements are present,” he said.

Kato said these were enshrined in the MOA-AD. “I will support an agreement which completely embodies the MOA-AD,” he said.

But he said he had lost hope and criticized the MILF for engaging in “protracted negotiations.”

In July 2009, both the government and MILF panels agreed to reframe the MOA-AD in the process of crafting a comprehensive compact. The MILF itself disclosed that the content of its proposed formula is at least 70 percent derived from the MOA-AD.

Self-reliant?

“We are only surviving here,” Kato described the BIFF’s main activity.

He claimed that he was not recruiting, but that his force had rapidly grown for the last six months, prompting him to “systematize the way we do things.”

“People are coming here and taking part in our movement voluntarily,” he added.

Holed up in an area which agricultural production activity is largely at a subsistence scale, questions continually arise about how the BIFF managed to survive. But Kato insists they are a “self-reliant” army.