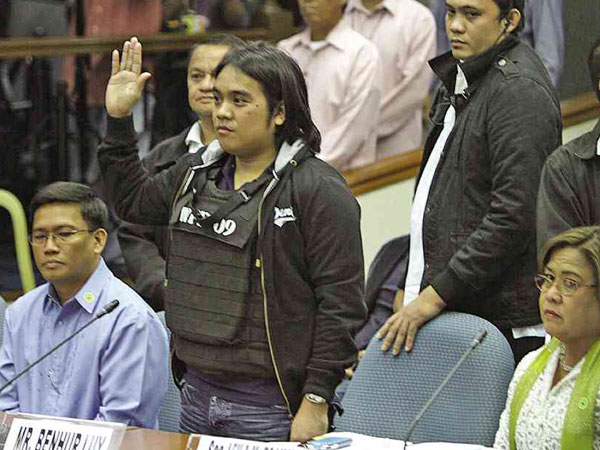

MAN OF THE HOUR Principal whistle-blower Benhur Luy, flanked by lawyer Levito Baligod, Justice Secretary Leila de Lima and security men, takes his oath during the Senate blue ribbon committee hearing on the massive pork barrel scam. Note that Luy is wearing a bulletproof vest. RICHARD A. REYES

“Maybe God used me to dismantle the work of my cousin.”

Benhur Luy, testifying before the Senate blue ribbon committee on Thursday, recounted how legislators trooped to his second cousin Janet Lim-Napoles to peddle their pork barrel when they learned they would get a kickback of at least 40 percent in a ghost project and an advance of half of the loot from the businesswoman awash in cash.

The cousin of the woman allegedly behind a P10-billion racket involving the congressional Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) said during his five-hour appearance in the nationally televised hearing that for senators, it was usually a 50-percent cut of the value of a project that her nongovernment organizations (NGOs) implemented.

Under the arrangement, Luy said Napoles would advance half of the kickback once the project was requested either through the House committee on appropriations or the Senate finance committee. He said legislators would get the remainder once the special allotment release order (Saro) was released by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM).

With half of a PDAF allocation usually pocketed by a legislator, Luy said 10 percent of the remaining amount usually went to implementing agencies as “SOP” (standard operating procedure or grease money).

Luy said Napoles could afford to “advance” kickbacks because she was “liquid.” He said there were days when she would withdraw as much as P75 million from her Metrobank or Landbank accounts. There was so much cash it covered her bed and filled her bathtub.

Senators receive P200 million each in annual PDAF while House members get P70 million each.

Walk-in customers

“When I joined Mrs. Napoles, there were already lawmakers who would go to the office—that was already a system in the office,” Luy said.

“They would go [to our office] and offer their PDAF,” he added. “[They would ask] if we would like to implement [their project].”

On some occasions, he said it was Napoles who would approach legislators and ask them to join the scheme.

“So they were walk-in customers, so to speak?” Sen. Francis Escudero asked Luy, who replied in the affirmative. The whistle-blower agreed with Escudero’s observation that the racket apparently spread among lawmakers by “word of mouth.”

The 32-year-old Luy said Napoles picked an “implementing agency” based on the “menu” of projects available at the DBM. By his reckoning, his former boss had “contacts” among these agencies, including the DBM.

Luy said a legislator’s kickback was usually delivered by Napoles’ driver to his or her house. But since Napoles was supposedly wary that the driver might pocket the money, she would require that “vouchers” be signed by whoever received the delivery.

“Sometimes it was the lawmaker himself [who received the amount], sometimes, the chief of staff,” he said, noting that vouchers usually had three copies.

“All vouchers contained the signature of whoever received the money, including the amount.”

Luy said the original copy of the voucher was kept by Napoles, the yellow one by her company’s accounting department, and the pink one by the lawmaker.

Such vouchers were said to be among the pieces of evidence the Department of Justice (DOJ) would use in the cases to be filed in connection with the PDAF scam.

Luy said a lawmaker received a minimum of 40 percent in kickback from a PDAF-funded project coursed through bogus NGOs put up by Napoles or her dummies. This meant that for a P10-million project, for instance, a legislator could get at least 4 million.

Luy said the entire project was usually a “ghost” one. But he said there were times when he and other employees of Napoles’ company made actual deliveries.

The 49-year-old Napoles is being held at Fort Sto. Domingo, an antiterrorism training camp of the Philippine National Police for the elite Special Action Force, for allegedly illegal detention of Luy. Luy’s rescue by the National Bureau of Investigation in March led to his revelations of the extent of Napoles’ racket over the past 10 years.

A medical technology graduate who went to work for his cousin in 2002, Luy agreed to testify on condition he would not name the lawmakers pending the filing of criminal charges against them in the Office of the Ombudsman next week. At least 14 people, including Napoles, are facing plunder charges.

Up to P75M in one withdrawal

He said in a 50-50 sharing scheme, Napoles got 40 percent of the face value of a given project and government “conduits” 10 percent and the rest went to the lawmaker.

He said certain projects were sometimes partially delivered to intended beneficiaries but the goods delivered such as “livelihood kits” were overpriced and were supplied by Napoles’ own trading firms.

“From Landbank, we would withdraw the money and bring it to the office. Just like in withdrawals from Metrobank, we would, for example, reserve P75 million,” Luy said on questioning by Sen. Teofisto Guingona III, the blue ribbon panel chair.

“If Ms. Napoles was not in the office, the money would be brought to her residence [at Pacific Plaza Towers in Taguig]. It would be taken from the elevator to the masters’ bedroom. Since it couldn’t possibly fit inside her vault, sometimes we would place it on her bed, sometimes in her bathtub,” Luy added.

He said the money was placed in bags stacked one on top of the other.

“In the case of (payoffs to) senators, their chiefs of staff go to the office,” Luy said.

“They fetch the cash?” Guingona asked.

“Yes sir,” Luy said. “There were instances… when she asked us to prepare the money because she was meeting with a senator, she didn’t tell us who. She would then bring the money to their meeting.”

Payoffs to bank accounts, aides

Luy said the Napoles group also transferred funds to congressmen’s bank accounts and some lawmakers’ chiefs of staff. He said he had in his possession bank account numbers.

He also said a senator received a manager’s check from Napoles but the check was under a different name.

In an earlier interview with Inquirer, Luy said the check was in the name of a known businessman “very close to the family of a senator.”

He said that 5 percent of the kickback was set aside for the legislator’s chief of staff. “If she managed to penetrate and talked directly [with the legislator], the chief of staff has no more share,” Luy said.

Luy said lawmakers called Napoles to tell her that they were about to submit a list of projects that would be funded by their PDAF to the DBM.

“What happens is Ms. Napoles buys the PDAF or the lawmakers would call her to tell her ‘we were about to submit our listing. What do you want to do?’ Ms. Napoles will tell them that she will first call the government agencies,” Luy said.

Luy said the members of Napoles’ staff would look at the DBM menu to identify which agencies they could use to place the PDAF. These include such groups as the National Agribusiness Corp., the National Livelihood Development Corp., the Zamboanga Rubber Estates Corp. and the Technology Resource Center.

Luy said that once the projects had been identified and listed by the DBM, Napoles would advance half of the lawmakers’ share. The other half comes after the release of the Saro from DBM.

Surge in 2006

Luy said it was in 2006 when Napoles started buying properties.

Asked by Sen. Ralph Recto how the clients of Napoles increased in 2006, the whistle-blower said, “Kasi po yung mga natalong congressmen pumunta sa office para magrefer (It was because lawmakers who lost in elections went to the office to refer [projects]).”

To which Recto replied, “Nag ahente na rin (they became agents [of Napoles]).”

On Recto’s repeated questioning about whether Napoles had a partner or someone higher up that she consulted or had instructed her on how to put up the fraudulent scheme, Luy said several times that no one was behind Napoles and she was the only “boss” they knew.

“Siya yung mastermind (She was the mastermind),” he said.

Influential boss

Luy said he had not given any money to a senator but admitted giving to their senior staff.

“There were also times the senators’ chiefs of staff would accompany them to the banks to withdraw the money,” he said.

He said that it was only in 2011, after working for 10 years at Napoles’ JLN company, that he and the other whistle-blowers learned of the illegal activities because of letters from the COA asking them to explain their projects.

“Even if we wanted to report it, we don’t know who to tell. We knew how influential our ‘boss’ was,” he said.

Sen. Bam Aquino asked: “At what point did you realize that what you were doing was illegal, immoral, wrong?”

Luy said it was when the Commission on Audit (COA) “wrote to us” in 2011.

“It was only then that you realized it?” Aquino said, sounding incredulous.

Country’s gratitude

Justice Secretary Leila de Lima told the senators that Luy and other whistle-blowers owed the country’s gratitude for exposing how funds meant for development aid were stolen by some lawmakers and bureaucrats.

De Lima said Luy was allowed to testify because it was in the public’s interest to have a representative of the whistle-blowers’ group testify in the open on things that people only got to read in the newspapers.—With a report from Nancy C. Carvajal

RELATED STORIES:

Senators got half from Napoles deals

Cash from PDAF fills up Napoles’ bathtub