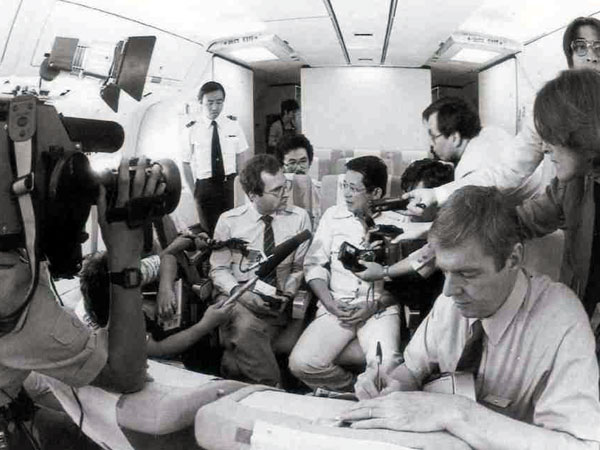

LAST INTERVIEW Twenty top foreign journalists accompany ex-Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr. on his flight from Taipei to Manila on Aug. 21, 1983.

(Editor’s Note: The writer, a former news editor of the Manila bureau of the Associated Press, is now head of the Inquirer News Service.)

“You’ve lost it!” a friend, an American news correspondent, exclaimed over beer a day after Ninoy Aquino was laid to rest without any upheaval engulfing the country. There was a tinge of reproach in his tone, the kind one dishes out to someone who has frittered away a rare opportunity to accomplish something big.

“Of course not,” I answered, barely masking my irritation. “Did you expect a revolution? Just wait and see.”

The wait would take two-and-a-half years. And how sweet the outcome was, precisely because it was not accompanied by the conflagration my parachutist correspondent-friend might have been expecting.

The assassination of Ninoy Aquino on Aug. 21, 1983—not the first botched coup attempt by Juan Ponce Enrile et al.—set off a chain of events that ended the 14-year dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and swept Aquino’s widow, Cory, to power.

There is no denying, of course, that the struggle against the Marcos’ dictatorship began the day he declared martial law, although he always had the upper hand—until the Aquino assassination began to unravel his regime.

It was a bright sunny Sunday. A sense of expectation was in the air. On my way to the office, I noticed people stringing yellow ribbons on trees and on street iron railings. Not a few cassette players blared out the tune “Tie a Yellow Ribbon ’round the Ole Oak Tree.”

Coming home

I was news editor at the Manila bureau of the Associated Press (AP) then and, by some conspiracy, I was chosen to man the desk that day, which happened also to be my day off. AP chief of bureau David Briscoe, newsman Ben Alabastro, photographers Andy Hernandez, Alex Baluyut and photo stringer Bullit Marquez, then a budding photo journalist, headed to the airport.

Reminiscing that day with Marquez and Recto Mercene, who was then working for the Times Journal but is now connected with Business Mirror, I figured I was designated deskman perhaps because I was skeptical Aquino would really come home.

He would not be stupid to return to jail, I thought. Besides, a month or so earlier, I was sent to Tokyo to cover Ninoy’s scheduled arrival there on the first leg of his homecoming. But he called the trip off after Imelda Marcos warned that the government, which had sentenced Ninoy to death, had uncovered a plot to assassinate him.

No fear

That seemed to me to be all the more reason for him not to come home, but it turned out, as he had told the late journalist Teddy Benigno, then bureau chief of Agence France-Presse, he wanted to show Marcos he was not afraid of him.

Asked what I was doing in the office on my day off, according to Bullit, I replied, “I don’t know why David thinks Ninoy is really coming home.” I don’t recall saying that but I admit I could have, being a natural skeptic, even a cynic, in all my years in journalism.

Strangely for such a momentous event, apart from the sprouting of yellow ribbons, the repeated playing of the song about coming home to a yellow ribbon, and the fact it was the start of a virtually sleepless week, I have few recollections of that day.

With preliminary stories out of the way and my troops, as it were, deployed at the airport by midmorning, the long wait began.

We did not know what plane Ninoy was taking—the Marcos regime had warned dire sanctions against any airline that dared take Ninoy on board, thus his resort to the use of the name Marcial Bonifacio—nor his expected time of arrival. Bullit said someone tipped us it would be “around noon.”

Breaking news

So there they were: Briscoe and Alabastro at the lobby of the arrival area with photographers Hernandez and Baluyut. At the VIP lounge were Aquino’s mother, Aurora, other relatives and political allies—Lorenzo Tañada, Soc Rodrigo, Doy Laurel, among others. Bullit was positioned on the airport driveway, where Butz Aquino was leading a crowd of welcomers.

The second thing I remember vividly that day was Alabastro calling in the first break. Shots fired at the airport! Out went my first bulletin, words to the effect that shots had rung out at the Manila International Airport shortly after Aquino’s plane touched down.

Subsequent calls and updates came, even one from Briscoe saying Aquino was dead. Then Alabastro phoned in what turned out to be a monkey wrench: Airport Manager Louie Tabuena was saying Ninoy was alive and was taken away. That went out on the wires, too.

Poor United Press International (UPI). It had beaten us by hours with the news that Aquino had been killed, but this was probably one instance when being first did not pay off as it should have. US news media were reluctant to go with the UPI story. Why? Because The Associated Press had not yet confirmed Aquino was dead.

No matter, the three-man team at the Manila bureau of UPI, which is based in New York, received a citation of excellence in international reporting from the Overseas Press Club of America in Washington. In the same year 1983, the team headed by Boy del Mundo was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

Del Mundo now heads the Inquirer investigative team.

Cathay flight

UPI had its Pacific Division editor Max Vanzi with Aquino on the plane and he could tell Aquino was dead when he saw his figure sprawled face down on the tarmac. Confirmation of Aquino’s death from the family and the authorities came much later.

Briscoe was furious coming back to the office. I said I could not have ignored what Tabuena had said. After all how much more authoritative can one get about airport happenings than the airport manager himself?

Aviation Security Command (Avsecom) personnel and other military intelligence types, although not visible outside the airport, were all over the place.

Around noon, as Mercene recalled, a Cathay Pacific Airways flight from Hong Kong touched down. News photographers rushed out to meet it.

“We went down to where the luggage conveyor belts were. There were Avsecom soldiers who even offered to take us to the plane. We said we preferred to go on our own, and they let us. Negative … Ninoy was not aboard,” Mercene said, adding they went back to the Duty Free Shop area.

There, Mercene said, Col. Vicente Tigas, a Presidential Security Group officer in charge of liaison with the media, called the photographers. He read out from a list the names of the photographers allowed to take pictures. Tabuena was with him.

7 photographers

Only seven names were called out. Apart from Mercene, they were Manuel Silva of the Philippine Daily Express and Viznews, Louie Perez of Bulletin Today, both of them now deceased, Loy Caliwan of Balita, Ben Malumay of People’s Tonight, Carmencio Rosales, also of the Bulletin, and Jolly Riofrir, a videographer of the government propaganda machine National Media Production Center headed by the late Gregorio Cendaña.

Mercene recalled that Cendaña had called the photographers to a meeting over lunch on Aug. 20 at the Philippine Village Hotel.

Cendaña announced: “Ninoy is expected to arrive tomorrow. If you have photos na medyo malabo, dalhin nyo sa akin at ako na ang bahala (If you have photos that are not very clear, give them to me and I will take care of them).”

By “malabo” Mercene said he and the others understood photos uncomplimentary to the government.

After reading out the names, Tigas and Tabuena escorted the seven to the mouth of Bay 8, telling them to stay there.

“I doubt that Tigas knew then that Aquino would be shot,” Mercene said.

The photographers were away from the windows and in a place where they could see nothing of what would later take place on or near the plane.

“At 1 p.m. the China Airlines plane arrived. Then a man with a bag came out of Bay 8, saying, ‘They’re coming out.’ But we could not see anything,” Mercene said. “Then I heard what sounded faintly like a popping balloon. In a few more seconds we heard a succession of ‘pop, pop, pop…’ and we knew they were gunshots.

“Right away we went to the windows. I saw two people lying on the ground. I took a few shots before I noticed a soldier was pointing his gun at me, so I ducked but held up my camera and continued taking pictures. I did not know if I had captured anything.”

Of course, Mercene had. His photos of two men sprawled on the ground near an Avsecom van and two soldiers menacingly aiming guns at airport windows went around the world.

‘Hail Mary shots’

Mercene’s photos were what Marquez called “Hail Mary shots because you have to pray to capture something.”

“Then we stood up and waited for the passengers to file out,” Mercene recounted. “Then out came a woman who was crying and screaming hysterically.” She would eventually be identified as Rebecca Quijano, who was referred to in news accounts simply as “The Crying Lady.”

“She was crying and hysterical. ‘What is she saying?’ we asked each other. She was trying to tell us something which we could not understand, so we followed her. Then Tigas held her by the shoulder and led her away. We did not see her after that.”

By this time, Mercene said, he was in a state of panic.

“Pare, alis na tayo dito, baka yariin tayo (Let’s get out of here, they might do something to us),” Mercene recalled telling the other photographers. “I went out. My panic increased even more when I found the airport doors had been locked. I found out they were locked to prevent people outside from surging in.”

Fear of soldiers

Mercene said he went out of the terminal building via a small service elevator very few people knew existed.

Outside he glimpsed Laurel addressing several thousand welcomers through a bullhorn. “My countrymen,” Mercene quoted Laurel as saying in Filipino, “the man you have come to fetch has been shot. Ninoy has been shot.”

Afraid to go to his car for fear soldiers were waiting for him there, Mercene decided to return to the office by bus. “I did not go back for my car until after two days,” he said.

Getting to the office by around 4 p.m., he was surprised Tabuena was already there.

“What’s he doing here?” Mercene recalled the late Gani Yambot, who would eventually become the Inquirer publisher, asking him. He said he did not know.

He directed the photo lab man to develop his roll of film and print as many frames as he could.

Photos confiscated

Riofrir showed up at the Times Journal around 6 p.m. “The Boss wants to have the pictures that you took,” Riofrir said, apparently on a mission to confiscate whatever uncompromising pictures the press might have taken.

Mercene, still shaken and fearing what the government could do to him, replied: “I will give it to you on a silver platter. I gave him my entire roll of developed film. What he did not know was that I had a lot of prints made.”

Some of the photos ended up with the Associated Press and other news agencies.

Riofrir had also made the rounds of other media offices. At the AP, we gave him nothing. But then we also had nothing.

Mass of humanity

The following day, Benjamin “Kokoy” Romualdez, Imelda Marcos’ younger brother who owned the Times Journal, went to the Journal office and picked up a copy of the newspaper, which had bannered the assassination and used Mercene’s photos.

“He threw the paper on the ground.

P… ina, dyaryo ko pa ba ito? (S… .. b…, is this my paper?),” Mercene quoted Romualdez as saying, recalling the incident as recounted to him by a senior Journal editor.

“We made up for that,” Mercene said with sarcasm. “The day after Ninoy’s funeral our banner was the man hit by lightning at the Luneta.”

The story did not even say that the man had climbed up a tree to watch the millions of Filipinos who had lined up all the way to Manila Memorial Park in a funeral procession that took 10 hours to inch through the mass of humanity.