The healing world of a ‘mandadawak’

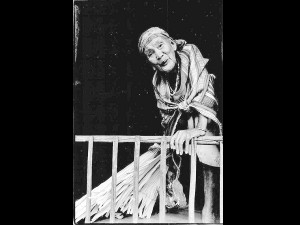

INA Ayunnaw, a “mandadawak” of Magsilay in Pasil, Kalinga province, performs a healing ritual in this 1988 photograph by Tommy Hafalla.

In 1988, the parents of a nursing child were told by doctors at a hospital in Tabuk, Kalinga province, that their ward’s affliction was beyond treatment.

Left with no options in conventional medicine, the couple took the child back to their hometown in Pasil to summon a “mandadawak,” a Kalinga healer. A ritual was soon performed to seek a possible alternative cure for the child who was described as emaciated and on the brink of death.

The child survived, according to photographer Tommy Hafalla who happened to be in Pasil that year, and thus heard that a healing ritual for the child was about to take place. During the ritual, he shot a number of frames using black and white film and emerged with a set of prints which included a window portrait of Ina Ayunnaw, the mandadawak.

Hafalla’s inside story of the photograph included his recollection of the healing process where, he said, the mandadawak “went into a trance-like state.” He remembered the healer as “old and feeble, and labored with every step.”

“But when she went into a trance, it was as if she was drawing her energy from a powerful source,” Hafalla said.

Article continues after this advertisementThis description of the manner in which the mandadawak conducts the healing ritual draws similarity to local healers in Africa and Central America. This is the Cordillera’s closest version to a shaman, said Dr. Esteban Magannon, a retired professor of social and cultural anthropology.

Article continues after this advertisementMagannon, who taught at the University of the Philippines (UP) and other institutions in Southeast Asia as well as in France, said “shamanism is a crucial aspect of

ethnomedicine” because of the healer’s role as conduit to the spirit world.

‘Spirit helpers’

In fact, the first step in the healing ritual, Magannon said, is for the mandadawak to call on “spirit helpers” in the “mythical world, nature or ancestral realm.” Having done this, it is important for the mandadawak to go into a trance as this would mean “she has gone with the spirit helpers to look for the entity that caused the illness.”

This is the essence of shamanism, Magannon said in a lecture at the UP Baguio’s Cordillera Studies Center on July 10. As a shaman, the mandadawak’s task is to “negotiate with the spirit that caused the illness and plead on behalf of the patient that he or she be

restored to good health.”

While in a trance, the “spirit will speak through the mandadawak” who is now a “medium,” and will unravel the cause of the illness, as well as the terms to be met before the patient is “cured” of his or her affliction.

From birth to death

Magannon, himself a Kalinga who did his research on the mandadawak from his village of Lubo in Tanudan town, said it was here where the ritual reaches the sacrificial stage in which animals would be butchered as offering to the spirits: “Either a chicken, pig or a carabao depending on the spirit that caused the illness.”

As a practitioner of ethno-medicine, the mandadawak determines the cause of illnesses based on the healer’s reference to the world. Magannon said the mandadawak believes that a state of well-being is dictated by the life cycle of human

beings—from birth to death.

The life cycle assumes an ideal condition where a person will “grow into his life without encumbrances.” Magannon said sickness happens when this growth is encumbered. “It is when a person’s bones, muscles and other organs are involved in disharmony that illnesses occur.”

Magannon said people exist along with other creatures as well as elements of the spirit world who all occupy specific spaces. When human beings encroach on prohibited spaces—the realm of the “paniyaw” (other beings)—they usually invite pain or sickness because the harmony between humans and elemental beings is disrupted.

Aside from space, Magannon attributed the determination of illnesses by the mandadawak to a disruption of “time.” He said “every human activity has its own time and place. If this is disrupted as when one sows crops that is out of season, sickness usually occurs.”

The ways in which one becomes a mandadawak is either through a spiritual mandate or apprenticeship. The former happens through a revelation (usually in a dream), while the latter follows a long period of learning from a mandadawak until the apprentice passes the “sangatan” stage or literally “scaling up a mountain.”

Magannon said during a ritual, the mandadawak establishes a relationship with the spirits to the extent where the healer

“assumes a different modality of being.” This happens as the mandadawak goes on a trance and conjures a “kalidudwa” or body double.

In 1988, stunned as he was that the old and feeble mandadawak was able to carry a medium-sized pig and whip it around the room, Hafalla knew that the old woman did that with help from her kalidudwa and the spirits.