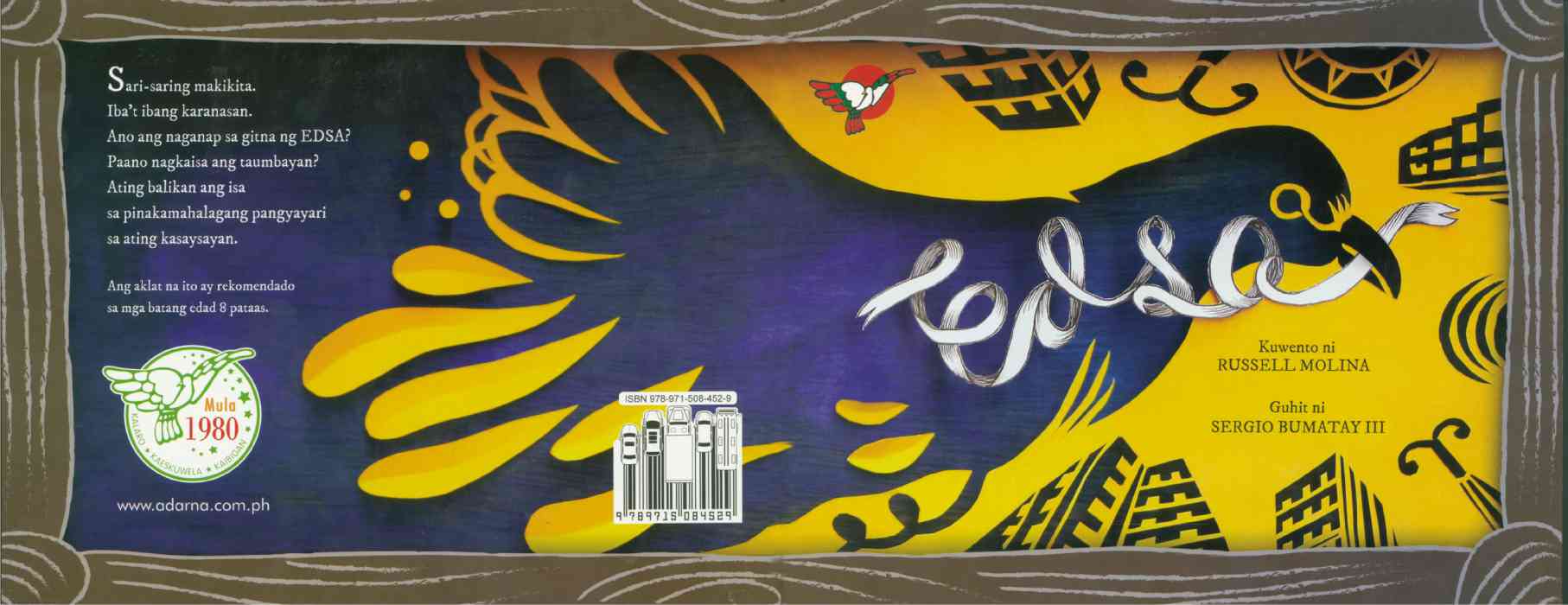

EDSA BOOK FOR KIDS A picture book, created by Russel Molina and Sergio Bumatay III, was launched on Tuesday to teach children the story of the four-day uprising in 1986 that toppled the Marcos dictatorship. “Edsa” is a counting book that presents images of people and objects connected to people power—one caged bird, two radio sets, three yellow ribbons tied around a tree, four student-activists and so forth. ANDREW TADALAN

How do you tell an 8-year-old child the story of a peaceful revolution that ousted a dictator and restored freedom and democracy in the country?

The Edsa People Power Commission (EPPC) on Tuesday launched a children’s picture book that parents and teachers can use to teach the young ones the story of the four-day popular uprising in 1986 that toppled the Marcos dictatorship and installed Corazon Aquino as President.

The picture book, simply titled “Edsa” and published by Adarna House Inc., is basically a counting book that presents images of people and objects connected to the revolution: one caged bird, two radio sets blaring the news, three yellow ribbons tied around a tree, four signing student-activists, five advancing soldiers, and so forth.

The ECCP said images of tanks and troops, priests and nuns, flags and flowers can be used by parents and teachers to interest the children in the history of the Edsa People Power Revolution and, at the same, time impart their own personal experiences to children about what life was like before and after the Edsa revolt.

President Benigno Aquino III’s sister, Ma. Elena Aquino-Cruz, Secretary Sonny Coloma of the Presidential Communications Operations Office, Education Undersecretary Dina Ocampo and activist-nun Sr. Sarah Manapol were among the guests at the book launching held at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

The book’s author, Russell Molina, and illustrator, Sergio Bumatay III, together with EPCC commissioners Emily Abrera, Milagros Kilayko, Cesar Sarino, Anton Mari Lim and Ogie Alcasid were also present at the ceremony, which coincided with the observance of National Children’s Book Day.

About a dozen first-grade students from Rafael Palma Elementary School in Malate, Manila, were also brought to the ceremony to listen to a storyteller read from the book.

Molina, a Palanca Awards recipient, said he wanted the new generation of Filipino children to find relevance in the spirit of Edsa and participate in the historical event.

“I think through a storybook like this, our kids can be part of that history and share in the value of that event. This project is also a wonderful way of keeping the spirit behind Edsa alive. In knowing their history, our kids can today further realize how unique and special they are in this world and how great being a Filipino truly is,” he explained.

Molina, who has been writing children’s books for over 15 years, said doing the Edsa story was the “hardest” thing he ever did, recalling that many stories about the revolution have been told and retold several times by different people.

“Looking back, I remember the whole event as having a sort of a tempo. It started quietly, then very much like an orchestra reaching a crescendo, that’s what happened. I remember my father putting a yellow ribbon on his car and going out of the house banging pots and pans to participate in the noise barrage,” Molina recounted.

“I thought about a counting book, something that also escalates, something that reaches a crescendo. I wanted the book to be highly interactive, and I felt that there’s power in that progression [of images],” he added.

The best way for children to understand the Edsa revolt is through reading with parents and teachers, he said. “Edsa” is a good vehicle for adults, especially those who were around during the revolution, to share their own story and provide meaning and personal context to the events written in the book, he added.

“I always believe that a picture book is a shared experience, with parents and kids, teachers and kids. More than just the country’s history, Edsa is also about personal histories. It is about families, friends, neighbors and many more,” he added.

The ceremony was accentuated by personal sharing by guests who remembered their Edsa days.

Ocampo said she insisted on going to Edsa despite the warnings of her father, a government employee, and slept on the streets. “Swooping military planes were our alarm clocks,” she shared.

Alcasid videotaped atop a hospital the hordes of people on Edsa but was unable to locate his friends on the street “because everyone was wearing yellow.”

Molina said as a young student in February 1986, he was not allowed to go out but he and his family were glued to their radio set “listening to and imagining [what was happening].”

It is left to the parents and teachers—using images such as the yellow-colored objects, the “Laban” sign, the streamers carrying the slogan “Katotohanan, Kalayaan, Katarungan” (Truth, Freedom, Justice), the caged bird that became free to fly again—to explain the background of the Edsa revolt and tell which person did what.

Alcasid admitted that the commission has a little difficulty reaching out to the youth to impart the Edsa story. Nevertheless, he said, the story needs to be told.

“It shaped our history. It’s better that they know because nowadays, it’s really hard to tell it. We are hoping that through the book, they are able to identify later the characters who are involved in that event and at the same time they learn something like counting,” he told the Inquirer.

Sister Sarah, for her part, said children familiar with Jose Rizal and Andres Bonifacio should also be familiar with the heroes of Edsa such as Ninoy and Cory Aquino, of recent history.

“They have to know what happened, the symbolism, how we were liberated from dictatorship. They (children) don’t know what life was like then under a dictatorship. Right now, the freedoms we are experiencing are because of Edsa. They have to know so that they can compare what it was like before, then and now,” she said.

Abrera said the book is dedicated to “all who stood against tanks and bullets in Edsa in 1986.” She said the EPCC wishes the book to be “a tool of remembrance and learning, a mine of inspiration, from which our families can continue to draw energy and uplifting moments.”

“It is a story our children must hear, for at Edsa, the world saw the best of the Filipino spirit. The courage, the deep sense of duty, the love of freedom and peace are among the ideals worth sharing and passing on,” she said.

The EPCC was created in 1999 by then President Joseph Estrada with the task of perpetuating and propagating the spirit of the 1986 popular uprising. The body is currently chaired by Executive Secretary Paquito Ochoa Jr.