Do Cordillerans really want autonomy?

(Editor’s Note: The author is the representative of the lone district of Ifugao and was chair of the House committee on national cultural communities in the 15th Congress. A former NGO worker, he served as mayor of his hometown Kiangan and later governor of Ifugao before being elected representative in 2010 and 2013. The Inquirer Northern Luzon solicited his views on autonomy as the Cordillera Administrative Region celebrates its 26th anniversary this month.)

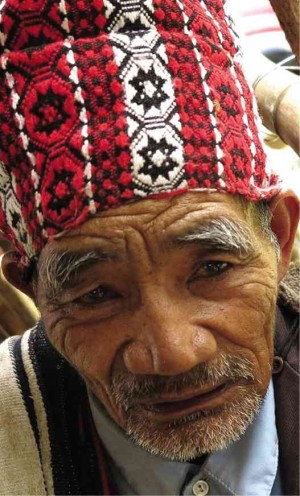

FOR THE ORDINARY . Cordilleran, regional autonomy should help define his struggle for self-determination and uplift his life. EV ESPIRITU

The quest for Cordillera autonomy is a decades-old struggle awash with the blood of martyrs, like Kalinga chieftain Macli-ing Dulag and nameless others who fought attempts by multinational corporations, private armies and the national government to seize control of our ancestral land and the natural resources.

It is borne out of years of oppression and exploitation.

Autonomy’s roots were imbedded more than a century ago when Cordillera tribes fought Spanish rule even without the concept of nationhood in their minds. Simply put, Cordillerans will kill and die for their land.

The Americans established their dominion over the region by embracing the culture of the tribes and becoming “White Apos” or self-proclaimed adopted sons.

Succeeding governments tried to cajole the people into assimilating themselves into mainstream society through scholarship programs and jobs in the mines.

Still, some tribal leaders saw “national integration” as a cover to silence dissent from schemes to control and exploit the rich mineral and forest resources of the Cordillera.

Conrado Balweg’s Cordillera People’s Liberation Army (CPLA) was born out of this dissent. It waged war against the government, not out of ideological underpinnings but fueled by the beliefs that this land is ours and that it is for us to decide what we want to do with it.

When then President Corazon Aquino and Balweg, a former Catholic priest, signed a peace pact in 1986, one of the conditions of the CPLA was a Cordillera under a regional autonomous setup. That was the birth of the concept of a regional autonomous government.

The framers of the 1987 Constitution formalized this in one of its provisions, Article X, Section 15, which states: “There shall be created autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao and in the Cordillera, consisting of provinces, cities, municipalities, and geographical areas sharing common and distinctive historical and cultural heritage, economic and social structures, and other relevant characteristics within the framework of this Constitution and the national sovereignty as well as territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines.”

But since that time, there have been two failed attempts at getting autonomy approved by the Cordillerans. However, it is incorrect to say that the Cordillerans do not want autonomy simply because they overwhelmingly rejected the autonomy laws in plebiscites in 1990 and 1998.

I believe we voted not on the issue of autonomy itself but on the structure of autonomy as contained in the organic act and the personalities behind the drive for autonomy.

People voted “no” for various reasons. The Catholic hierarchy launched its “no” campaign with the message that autonomy would just add another layer of corruption where politicians would grease themselves with the pork of P10 billion a year. The Left boycotted the plebiscite, saying that the organic act left sovereignty over natural resources at the behest of the national government.

There were parochial sectoral concerns, like the fear of government employees that their salaries would be lessened under a regional government. Then there were tribes that rejected the organic act simply because they did not want politicians identified with the autonomy drive to lord it over the region as corrupt kings.

Third attempt

Now, 15 years after the last plebiscite, I am mulling over a third attempt to pass an organic act by refiling the bill for a Cordillera Autonomous Region in the 16th Congress.

But the questions persist, the same queries President Aquino asked when I first sought his opinion on autonomy: Are the Cordillerans ready for autonomy? Is it something they really want?

A recent survey conducted by the Regional Development Council seems to bolster this reflection. In most of the six Cordillera provinces (Abra, Apayao, Benguet, Ifugao, Kalinga and Mt. Province) and Baguio City, the majority (40 to 60 percent of respondents) were either unaware of autonomy or undecided about it.

I ask myself what seems to be the conundrum, considering that most of the region’s political leaders are behind autonomy? And there’s no doubt that billions of pesos in funds promised in the proposed bill could lead to economic growth in the region.

Perhaps this was the reason the previous attempts failed. Perhaps there were feelings of indifference, apathy and indecision about autonomy because we were fixated on the money and the political power that accompanied it.

We failed to focus on the essence of autonomy, on the reason our ancestors fought and died so that we could talk of self-rule today—which is the right to self-determination.

We must reinvent our information and education campaign on autonomy. The messaging must be enticing and innovative. We should start on the historical premise of self-determination for the sake of our young who are unaware of the heroism of Macli-ing, the saga of Balweg, and the gallant resistance of our forefathers against foreign invaders.

Then we can proceed to discuss with all sectors in the community—farmers, government employees, tricycle drivers and businessmen—on how an autonomous Cordillera will benefit their lives, and not just the pockets of politicians.