The painting is a portrayal in oil of Jesus’ parable as recounted in Luke, which Jesus told in answer to a lawyer’s question, “And who is my neighbor?” The parable is about a man, traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho — an inhospitable stretch of countryside — who fell among robbers, who not only stripped him of his belongings but also beat him and left him on the road for dead. Three men came his way, the first two — a priest and a Levite — avoided him and passed on the other side. Help came from the third, an unlikely source, since he was a Samaritan, the Jew’s adversary, who was not to have dealings with the injured man. Jesus said, “But a Samaritan, as he journeyed, came to where he was, and when he saw him, he had compassion, and went to him and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; then he set him on his own beast and brought him to an inn, and took care of him.”

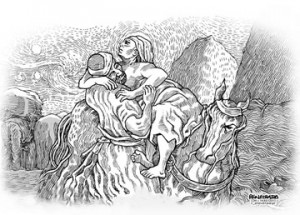

Delacroix’s painting shows the Samaritan lifting the hapless Jew and laying him on top of his horse. It is a forceful painting by the leader of the French Romantic school — the colors and the brushstrokes conspire to convey the solicitude that flows in the veins of the Samaritan’s powerful arms, now put in the service of wounded humanity.

Van Gogh’s copy is a mirror image of Delacroix’s work. But it has Van Gogh’s trademark — the swirling shades of blue that evoke the skies of his “Starry Night,” and the yellows that have strayed from his Sunflower series. But the figures locked in an embrace of brotherly compassion, including the patiently waiting horse, remain Delacroix’s. In a letter to his brother Theo, Vincent van Gogh summarized what he learned from the exercise of copying, from Delacroix, in particular: “What I admire so much about Delacroix… is that he makes us feel the life of things, and the expression of movement, that he absolutely dominates his colours.”

This morning, while we were on our way to work, and waiting for the traffic light to change, an old woman approached our car. The wife, who was driving, made a motion, suggesting that we should give her a coin — which was no big thing, because we kept some loose change within reach for routinary almsgiving. Still I wondered, if the woman were to be attacked and stabbed by a deranged man, would we stop the car and take her to a hospital, or would we just speed away, assuring ourselves with the thought that there were many other people who would help her? Besides, considering my work as a judge, there were matters awaiting that should not be delayed.

I found this troubling, because I felt that Jesus expected me in such a situation to be a mirror image of the Good Samaritan. And I told myself, “That’s just like him, to throw the lives of those who want to follow him into disorder, and turn their priorities upside down. For the sake of wholeness, to perfect their love.”

Which is different from what Delacroix and Van Gogh sought — to perfect their art.