New gene sequencing yields healthy baby

PARIS – Scientists said Monday they had used a new-generation gene sequencing technique to select a viable embryo for in-vitro fertilization (IVF) that yielded a healthy baby boy.

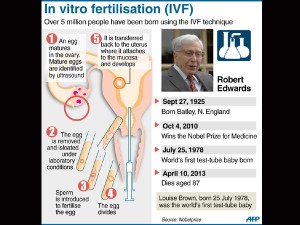

IVF, the process whereby a human egg is fertilized with sperm in the laboratory, is a hit-and-miss affair, with only about 30 percent of fertilized embryos resulting in pregnancy after implantation.

The reason for the high failure rate is not clear but genetic defects are the prime suspects, according to the authors of the paper presented Monday at a meeting in London of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE).

The new method, known as next generation sequencing or NGS, uses updated technology to sequence an entire genome— revealing inherited genetic disorders, chromosome abnormalities and mutations.

Study author Dagan Wells of the University of Oxford’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centre said the new technology was “inherently cheaper” and yielded more genetic data than older methods.

Article continues after this advertisementIt provides millions of fragments of DNA from a single cell which are then sequenced by a computer.

Article continues after this advertisementThe method has started being used in genetic research and diagnostics, but not yet in embryo screening, according to Wells.

“Many of the embryos produced during infertility treatments have no chance of becoming a baby because they carry lethal genetic abnormalities,” he said in a statement.

“Next generation sequencing improves our ability to detect these abnormalities and helps us identify the embryos with the best chances of producing a viable pregnancy.”

Current methods of detecting embryonic gene deficiencies add over £2,000 (2,300 euros, $3,000) to a single IVF attempt, said Wells.

“The new method should allow costs to be reduced by several hundred pounds, potentially bringing the benefits of chromosome screening within the reach of a far greater number of patients,” he told AFP.

Wells had tested the method on “abnormal” embryos in the laboratory until he was satisfied of a high level of accuracy, then used it to help two couples undergoing IVF.

The mothers were aged 35 and 39, and one had previously had a miscarriage.

Wells said the method identified three healthy blastocysts (early embryos) in one couple and two in the other.

A single embryo was transferred to each woman, leading to healthy pregnancies in both cases, said the statement.

“The first pregnancy ended with the delivery of a healthy boy in June” in Pennsylvania.

The second mother “will be delivering soon,” said Wells.

Further tests will be carried out later this year.