VATICAN CITY— A Vatican cleric and two other people were arrested Friday by Italian police for allegedly trying to smuggle 20 million euros ($26 million) in cash into the country from Switzerland by private jet. It’s the latest scandal to hit the Holy See and broadens an Italian probe into its secretive bank.

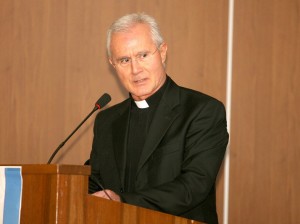

Monsignor Nunzio Scarano, already under investigation in a purported money-laundering plot involving the Vatican bank, is accused of corruption and slander and was being held at a Rome prison, prosecutor Nello Rossi told reporters.

Scarano’s arrest came just two days after Pope Francis created a commission of inquiry into the Vatican bank to get to the bottom of the problems that have plagued it for decades and contributed to the impression that it’s an unregulated, offshore tax haven.

Francis has made clear he has no tolerance for corruption or for Vatican officials who use their jobs for personal ambition or gain. He has said he wants a “poor” church that is concerned for the world’s needy, and he has also noted, perhaps tongue in cheek, that “St. Peter didn’t have a bank account.”

Prosecutor Rossi said the Swiss operation involved three people, all of whom were arrested Friday: Scarano, a recently suspended accountant in the Vatican’s main finance office, Italian financier Giovanni Carenzio, and Giovanni Zito, who at the time of the plot was a member of the military police’s agency for security and information.

Rossi detailed a remarkable plot — uncovered by telephone wiretaps — in which the three allegedly planned to bring into Italy some 20 million euros in cash that financier Carenzio held in his name in a Swiss bank account without paying customs at the airport, as would be required.

Scarano’s attorney, Silverio Sica, said his client was something of a middleman: The 20 million euros belonged to friends who had given the money to Carenzio to invest but wanted it back. The plot would presumably enable them to avoid paying customs fees or having any paper trail of such a large amount of money entering Italy.

Rossi identified the friends as members of the Italian shipping family d’Amico and said that the money was “presumably” being held in Switzerland to avoid paying Italian taxes. An email seeking comment from the family’s Rome-based company, the d’Amico Societa di Navigazione SpA, wasn’t immediately returned.

According to prosecutors, Zito, the agent, called in sick to his job one day in July 2012, rented a private plane and flew with Carenzio to Locarno, Switzerland. There, Carenzio was supposed to withdraw the cash from his bank account and hand it over to Zito to bring back to Italy. The plan was so detailed there was even to be an armed police escort waiting at the airport to bring the money to Scarano’s apartment in Rome, Rossi said.

“This operation was meticulously planned in all its details,” Rossi said, noting that Zito was chosen to be the mule specifically because his high-ranking position in the Carabinieri would have enabled him to pass through the airport customs area without being stopped.

The money could have been transported relatively easily because euros are issued in high denominations. If the cash had been withdrawn in the largest denomination — 500 euro notes — it would have weighed 44 kilograms (97 pounds) and fit in a suitcase.

But at a certain point in Locarno, the deal fell through and Carenzio made excuses that the bank couldn’t come up with the money, Rossi said. He declined to identify the bank.

Zito returned to Rome empty-handed but still demanded from Scarano his fee of 600,000 euros for the operation. Scarano cut him one check for 400,000 euros which he deposited. He gave him a second check for 200,000 euros, but in a bid to prevent the check from being deposited, reported it as missing, the prosecutor said.

That put a block on the check and resulted in Scarano being accused of slander for filing a false report knowing that the check was in Zito’s hands, Rossi said.

Scarano, as well as the other two, are also accused of corruption. If they are indicted and convicted, they could face up to five or six years in prison, prosecutors said.

Sica, the lawyer, said Scarano said his client would respond to prosecutors’ questions.

The Vatican bank, known as the Institute for Religious Works, or IOR, is cooperating with Italian authorities and its lay board has launched an internal investigation, spokesman Max Hohenberg said.

Rossi, the Italian prosecutor, described the operation as one branch in a “mosaic” of investigations targeting the IOR, which has long been a source of scandal for the Holy See. That said, the Swiss investigation didn’t immediately appear to directly involve the IOR.

The checks Scarano wrote to Zito, for example, came from an Italian bank account, prosecutors said. They declined to say if Scarano received any payment for his role in the plot, or if his IOR account was used at all.

Rossi’s team of prosecutors in 2010 placed the top two Vatican bank officials under investigation for allegedly violating anti-money laundering norms during a routine transaction involving an IOR account at an Italian bank. They ordered the 23 million euros in the transaction seized. The money was eventually unfrozen but the two men remain under investigation.

Rossi’s team is also working with prosecutors in Salerno on a separate money-laundering investigation involving Scarano and his IOR account.

According to Sica, the lawyer, Scarano took 560,000 euros ($729,000) in cash out of his IOR bank account in 2009 and carried it out of the Vatican and into Italy to help pay off a mortgage on his Salerno home.

The money had come into Scarano’s IOR account from donors who gave it to the prelate thinking they were funding a home for the terminally ill in Salerno, Sica said.

To deposit the money into an Italian bank account — and to prevent family members from finding out he had such a large chunk of cash — he asked 56 close friends to accept 10,000 euros apiece in cash in exchange for a check or money transfer in the same amount. Scarano was then able to deposit the amounts in his Italian account.

The lawyer said Scarano had given the names of the donors to prosecutors and insisted the origin of the money was clean, that the transactions didn’t constitute money-laundering, and that he only took the money “temporarily” for his personal use.

The home for terminally ill was never built, though the property has been identified, Sica said.

The Vatican spokesman, the Rev. Federico Lombardi, said Scarano was suspended more than a month ago and that the Vatican was taking the appropriate measures to deal with his case. He said the Vatican had confirmed it was prepared to offer its “full cooperation” to Italian investigators.

On Wednesday, Francis named five people to head a commission of inquiry into the Vatican bank’s activities and legal status “to allow for a better harmonization with the universal mission of the Apostolic See.”