The government is offering P18,000 to each of the 20,000 families of informal settlers living along waterways in Metro Manila so they can rent decent and safe homes elsewhere for 12 months while officials are looking for a place to resettle them permanently.

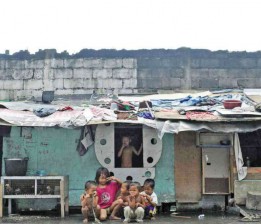

But the NGO Urban Poor Associates (UPA) sees the government offer—its monthly equivalent of P1,500 is just enough to rent a room in a squatter colony—as a “band-aid solution” to the housing problem.

“We did some pencil-pushing. It’s cheaper if we give them P18,000 to go to a safe place,” Interior Undersecretary Francisco Fernandez, the official in charge of relocating 100,000 families in the metropolis out of danger areas, said in an interview by phone.

If the informal settlers choose to stay in their hovels along estuaries or under bridges, the government will end up shelling out more for their relief, rescue, rehabilitation and evacuation when the waterways flood during typhoons, Fernandez said.

The relocation assistance for the 20,000 families runs up to P360 million, he said.

“It ends up very expensive,” he added.

Aquino’s plan

In 2011, President Aquino unveiled a P50-billion relocation plan for the 100,000 families of informal settlers, or P10 billion a year until he steps down in 2016.

It has been two years since, but the program has not taken off yet, mainly because of the difficulty of finding a resettlement place that is not only safe, cheap and decent but also accessible so that the resettlers’ livelihood will not be disrupted.

And then the government’s point man, Interior Secretary Jesse Robredo, died in a plane crash in August last year, and local officials requested that the clearing of waterways be put off in view of the elections in May this year.

But with the prospect of massive flooding in the metropolis coming with the onset of the rainy season, officials are scrambling to implement the plan.

The government aims to relocate 19,440 families to be able to clear eight major waterways that flow into Manila Bay, and ease flooding.

Public Works Secretary Rogelio Singson last week admitted that the clearing of the waterways could not be completed until yearend.

But with the financial incentive for the informal settlers, the job could be hastened.

The offer of P18,000, however, doesn’t appear enticing to the UPA, which argues that a poor family may be able to rent a room for a few months with that money, but it will still be in the slums somewhere in the city.

“It’s the same,” UPA information officer Princess Asuncion said. “Their solutions are bad and a waste of money. How many urban poor are they planning to relocate, and you’ll give them P18,000 each? All are band-aid solutions.”

DSWD help

Fernandez acknowledged that with P1,500 a month, the families were likely to find rooms only in slums. But he gave assurance that they would not be fending for themselves, as they would be assisted by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD).

“There will be counseling and social support from the DSWD. This is like a modified CCT (conditional cash transfer),” he said.

As the families leave, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) will dismantle their shanties and dredge the waterways, increasing their capacity to carry water during heavy rain.

Also, the National Housing Authority (NHA) will double its efforts to build in-city or off-site permanent relocation areas.

“We’re hitting many birds with one stone,” Fernandez said.

UPA executive director Denis Murphy, a former Jesuit priest who has been working with the poor in the capital for years, said it would be more prudent to relocate the families when their permanent homes were ready.

Proximity to jobs

Murphy conceded that informal settlers are clogging waterways, but said the ones he knew were moving.

“They should make a real effort to develop near-city, in-city relocation and after a year the people will be very happy to move. The people know what’s best for them. If it’s a safe place where the children can play, enjoy fresh air, and it’s near the people’s work, they’ll rush to it,” he said by phone.

“Living on esteros is not nice. How to deal with that, that’s where we differ,” he added.

Murphy reminded officials about the Urban Development and Housing Act, which set limits on evictions, and the President’s “covenant with the poor,” which restricted resettlement to on-site, in-city and near-city areas.

But Murphy did not rule out the possibility that the poor—and the public at large—are being taken for a spin whenever they are told that they are being relocated for their own good.

He said most families were complying with the standard 3 meters away from the waterway, contrary to perceptions that they were blocking the waterways.

“This idea that they’re saving lives by getting people out, I don’t know how many of them really believe that,” he said.

Slow to build

Sixty percent of the 100,000 families of informal settlers in the metropolis live along waterways. Of these, close to 20,000 are along major waterways: San Juan River, Tullahan River, Manggahan Floodway, Maricaban Creek, Estero Tripa de Gallina, Pasig River, Estero de Sunog Apog and Estero de Maypajo.

The NHA has so far constructed 4,500 off-site housing units in Bulacan and Laguna, and is expected to add 3,500 in-city units in Manila, Caloocan and Mandaluyong by October, or a total of 8,000 units.

But the job doesn’t stop there. Some 12,000 units more are needed to house all the 20,000 families. That’s why Social Housing Finance Corp. is offering financing for the families of informal settlers to build their own homes within the city, Fernandez said.

Families who accept off-site homes, or opt to rent within the city while awaiting for a permanent house, will be given P18,000 each, he said.

Originally posted: 9:32 pm | Sunday, June 23rd, 2013