(First of a series)

The birth pains that marked the launching last year of K + 12—a bold program meant to align the Philippines with the global 12-year basic education cycle—are not going away soon, along with the usual problems encountered at the beginning of each school year.

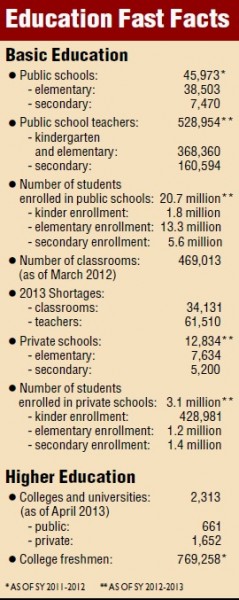

A quarter of the Philippines’ nearly 100 million population are students—some 21 million of them enrolled in more than 46,000 public schools and the rest in private facilities, according to statistics from the Department of Education (DepEd) for the school year 2011-12. (Figures from the last school year remained unavailable.)

Classes in public schools begin Monday—in some impoverished areas under the trees and still in others under tents, particularly in the Compostela Valley, where buildings were flattened in the devastating onslaught in December by Typhoon “Pablo” and remained unbuilt.

On May 15, President Aquino signed into law the program mandating Filipino pupils to attend kindergarten, six years of elementary school education, four years of junior high school and two years of senior high school. The signing officially ended the country’s 10-year basic education cycle, which now exists only in Angola and Djibouti.

New learning materials under the revised curriculum for Grade 2 and Grade 8 (formerly second year high school) will again be delivered late, as in last year when the K + 12 program was rolled out. As in the previous year, teachers did not have enough time to prepare. They only had a five-day mass training just before the start of classes.

Still, this second year of the program’s implementation should be better as the DepEd gains experience, said Armin Luistro, the education secretary and former president of De La Salle University, in a recent interview.

“It’s not generally understood and quite hard to explain that the K to 12 is a curriculum reform that involves changes in textbooks, changes in classrooms, retooling of teachers, etc.,” said Luistro. “Even if there is no K to 12, we have to address the backlog in classrooms, toilets, teachers, etc.”

The DepEd started revising the basic education curriculum the past school year in Grades 1 and 7.

“In any undertaking the first year of implementation is faced with a lot of glitches, challenges,” said Education Assistant Secretary Jesus Mateo when asked about the rushed training of teachers and the long delays in the delivery of the learning materials.

For the new curriculum for Grades 2 and 8 this year, the learning materials would again be delivered late, although Mateo promised these would reach the teachers and students earlier—“by the end of June or early July.”

“We made (the curriculum change) gradual, so we will improve as we move along the full implementation. This year will not be as problematic as last year,” he said.

A major change this year was the decision to tap the DepEd’s own experts in the field and in the main office to develop and train the teachers for the new curriculum.

The department previously sought the help of mostly university educators as subject area convenors to develop the teachers’ and learners’ materials.

Training

This time, the DepEd’s Bureau of Elementary Education (BEE) took the lead for the Grade 2 curriculum development, while the Bureau of Secondary Education (BSE) handled the Grade 8 curriculum, working with DepEd teacher experts.

“This is a lot better than last year. We learned. The training was better-planned. There was even a chief trainers’ training before the trainers’ training. We learned from the experience last time,” said BEE education program specialist Galileo Go.

The trainers attended a seven-day program in April. The national training for the Grade 8 trainers was held in Baguio City on April 14-20. Three sets of training were held for the Grade 2 trainers: in Quezon City for Luzon, Cebu City for Visayas-Mindanao, and in Iloilo City for a special training session for the province.

The mass teachers’ training started after the May 13 elections.

Leversia Rivera, an English teacher at Manila Science High School for the last 14 years, said the training had improved but it was still not enough.

She took part in the training for Grade 8 teachers from Manila, Caloocan and Pasay City public schools on May 20-24 at Philippine Normal University. She said the teachers who underwent the mass training last year appreciated the exercise this time.

Incomplete materials

However, the teachers were handed only a curriculum guide consisting of a few pages, and teaching modules contained lessons only for the first quarter, Rivera said. “It’s hard to see the continuity when you do not know where you’re supposed to go by the end of the school year,” she said.

“We can’t blame the trainers since these were the same materials given to them. They assured us the lessons up to the fourth quarter period have been completed. Maybe it’s in the production,” she went on.

The teachers nevertheless pooled their resources to get soft copies of all the materials available and reproduced these at their own cost.

Go, who was the lead trainer for the revised Grade 2 English subject, said the teacher’s guides were ready by December last year so the bureau had more time to plan and prepare the training modules.

Unlike in the pilot year when the subject area convenors developed all the Grade 1 learning materials, including those for the various Mother Tongue subjects, the Grade 2 learner’s materials were devolved to the DepEd regional offices.

Using the learner’s guide developed by the BEE in Filipino, the DepEd regional offices tailor-fitted the materials per subject according to their language and cultural context.

K + 12 reverted to a multilingual education with the use of the mother tongue (the language a child uses at home) as a medium of instruction from kinder to Grade 3 and as a separate subject from Grade 1 to Grade 3.

The DepEd is employing 12 major local languages—Tagalog, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Iloko, Bikol, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Tausug, Maguindanaoan, Maranao and Chabacano—introduced as a subject in Grades 1 to 3 in select schools.

The teacher’s guides, however, are all written in English.

Not enough training

Five days of training is admittedly not enough, Go said, especially since teachers in the lower grade levels usually handle most if not all of the subjects in their grade level.

The same teachers who underwent the Grade 1 curriculum training also turned up for the Grade 2 curriculum training.

“Grade 1 and 2 teachers can teach all the subjects,” said Go, who had taught all grade school subjects as a teacher and acting principal in Mogpong, Marinduque, before he joined the DepEd in 2004.

BSE education program specialist Marivic Tolitol said the Grade 8 curriculum was completed earlier than last year.

A physical education teacher before she joined the DepEd in 1998, Tolitol said she used to simply follow the lesson outline of the textbook.

“Before, I did not know there was a framework. I did not know why I was teaching these topics. I thought the textbook was it. But in fact you have to adjust the textbook according to the scope and topics you are teaching,” she said.

She said the topics in the new curriculum were arranged to build on skills that had been acquired.

“If you simply follow the textbook, you do not understand the prerequisites,” she said. “There is a very big change (in the new curriculum). Now the focus is to teach for understanding, not for facts or low level information.”

The Grade 8 learner’s guide, or learner’s material, per subject area is a thick pile of loose sheets bound together, Tolitol said. The learner’s material for Filipino has about 500 pages.

Real-life applications

With a revised curriculum, the existing textbooks in schools are no longer the primary source of materials but have instead become supplements to the new learning concepts developed by the DepEd.

“The textbooks are references but the exercises are already included in the materials. There are built-in readings,” Tolitol explained.

The emphasis on real-life applications of learning also opens the door to tapping resources outside the classroom.

“We have very rich resources, like people, parents and the people in the community. The Internet can be a resource. If you depend on the textbook you’re not even sure if it was printed correctly,” she said. “Don’t get me wrong. Textbooks are important. All we’re saying is we should not be limited to the textbook.”

The Grade 2 learner’s materials, on the other hand, are in book form.

Go said the department had taken note of the activities in the existing textbooks that the teachers could still use in the new curriculum.

“If the learners’ materials are not yet there, they make their own on Manila paper,” he said. “If I will teach again, it’s better now because we have a lot of materials. Before, when I was in the mountains, I had no textbook. We were using Manila paper. I did everything.”

Spiral approach

Rivera said she appreciated the curriculum framework, including the “spiral approach” in tackling lessons, but believed the new curriculum would work only under ideal school conditions.

“In itself, the spiral approach is good and will ensure understanding so students can apply knowledge and competencies and be lifelong learners. Given favorable conditions, it will really work. But there are the realities. In some schools there are 80 students in a class,” she said.

As a specialized school, Manila Science High School has the ideal class size of 35 students.

Rivera said teachers would cope even if the implementation was in a trial-and-error stage.

“Teachers are inherently creative and resourceful. That’s how it is when you’re a teacher. We’ll do our part. We hope DepEd central [office] would do its job and ensure the basic inputs,” she said.

Mateo said the result of the K-to-12 reform would be known when pupils who entered kindergarten in school year 2011-12 had been through the new curriculum.

“The impact will be seen after six years because for those who will enter kinder, the assessment is when they finish (elementary school),” he said.

Planning senior high

The DepEd, meanwhile, has its eye on the fast-approaching 2016, when the added senior high school kicks in nationwide.

Luistro outlined general plans to give high school graduates viable options other than having to get a college degree to land a good job.

High school education is currently a “one-size-fits-all” program that assumes all graduates are meant for college, the department says. High school graduates who cannot afford college cannot land good jobs.

To help plan for the major infrastructure needs, Luistro said the department tapped the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to map out the capacity of private high schools as well as colleges and universities to absorb senior high students.

The government cannot build all the classrooms and hire all the teachers needed for senior high school, what with the need for classrooms and teachers going up each year in public schools.

Luistro said he was hoping for a 60:40 ratio between public schools and private schools in accommodating the more than 2 million senior high school students expected in 2016 and 2017.

Subsidizing students in private schools is less costly than if these students are in public schools.

“In principle, the government saves more if there are more students absorbed by private schools. But the question is, not all can be absorbed by private schools,” Luistro said.

2-year college vacuum

He said that extending subsidy to private schools would not only address the government’s logistical problem but also the concern of private colleges and universities, which would not have freshman enrollees in 2016 and 2017.

More importantly, the ADB mapping will also look into the senior high school programs that private schools plan to offer, whether in the regular academic track, the technical-vocational programs, entrepreneurial or the sports and arts courses.

Luistro wants senior high school programs to be tailor-fit for the locality in order to afford graduates who will not pursue college a good chance at employment or entrepreneurship.

“What we want in senior high school is specialized. If we will offer the same kind of programs, then all our graduates will compete for the same kind of jobs,” he said.

Senior high schools have to localize their technical-vocational or entrepreneurial programs, Luistro said.

“It will be easy if the province has a development plan, like Batangas has piers so it needs welders. The problem is if the province has no development plan, we have no basis to plan,” he said.

“We do not want a situation where since there is a fad for Tesda (Technical Education and Skills Development Authority) courses in beauty care, cosmetology, manicure and pedicure, you’ll have so many such graduates in a barangay. What will you all do? That’s the problem,” he said.

Luistro has suggested to Tesda the development of courses for scuba diving and surfing and others related to local tourism.

Dive spots in the provinces are a draw for tourists who stay for several weeks, he said, but the country has no diving academy.

23 tech-voc courses

During a recent visit to Siargao, Luistro said he saw three youths aged between 13 and 14 years who were not attending school because they were serving as surfing guides.

Luistro suggested a surfing academy in Siargao where the young guides could gain professional certification while attending school.

“There are core competencies, but the training should result in skills that can land them jobs,” he said.

Tesda said it had developed curriculum for technical-vocational courses, including automotive servicing, mechanical drafting, computer hardware servicing, horticulture, shielded metal arc welding, consumer electronics servicing, aqua culture, dressmaking/tailoring, masonry, care-giving, household services, plumbing, agricrop production, fish capture, handicraft, carpentry, electrical installation and maintenance, bread and pastry production, tile setting, animal production, fish processing and beauty care.

For the specialized technical-vocational courses in senior high school, the DepEd plans to tap practitioners as part-time teachers.

Republic Act No. 10533, or the Enhanced Basic Education law, more popularly referred to as the K to 12 law, allows schools to hire nonlicensed teachers as part-time teachers in high school.

“We can hire a bemedalled surfing coach who can teach surfing, or a Mangyan elder who has not finished college or high school but recognized as one who teaches values. The law allows this Mangyan elder to teach values education in the Mangyan communities,” Luistro said.

Luistro said the DepEd hoped to finish the mapping by November. “We have time to prepare,” he said.

(To be continued Tuesday.)