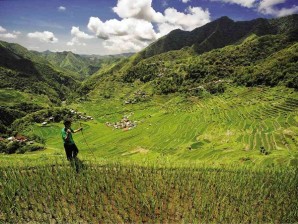

IFUGAO farmers have started planting rice again on portions of the Batad rice terraces which were scarred by landslides. Volunteer organizations, Ifugao residents and agencies like the Department of Agriculture helped repair most of the damaged terraces. EV ESPIRITU

BANAUE, Ifugao—European tourists, who negotiated the steep pathways leading to the Batad rice terraces in Banaue, Ifugao, on April 28 found little of the scarring that marred the picturesque, amphitheater-like relic.

Modern engineering techniques sometimes clashed with traditional knowledge when the government proceeded with the restoration work on the terraces, enshrined as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) in 1995.

But to the satisfaction of Batad villagers, most of the stonewalls ravaged by years of extreme weather and abandonment have been piled back in place, according to agriculture officials who inspected the rice paddies carved out on the mountainsides.

Work had been slow, admitted Agriculture Assistant Secretary Dante de Lima, who led the inspection. Every stage of repairs needed the accompanying ritual because the rice culture that built the terraces revolved around an old religion and mythology that some still practice today, said De Lima, who coordinates the Department of Agriculture’s (DA) national rice program.

The DA infused P20 million to repair the terrace walls that were eroded in 2011 by heavy rains dumped by Typhoons “Pedring” and “Quiel.” Landslides had washed away 102,663 cubic meters of soil from the terraces, the Ifugao Cultural Heritage Office (Icho) reported.

Raymundo Bahatan, provincial agriculturist, said 55 percent of the stonewalling work, or 4,280.90 cu.m. out of the targeted 7,721 cu.m. of restoration work, had been completed in Batad.

The government also commissioned contractors to build a protection wall, measuring 240 linear meters atop the Batad terraces, that would shield the terraces from debris falling off the mountaintop, where a watershed is being maintained.

But what worries De Lima is what the government has been introducing to the ancient terrace system in its attempt to restore the relics. More thought must be exerted in restoring the terraces after he was told that farm-to-market roads had been included in the government work package, he said.

The road, a tourism project, would destroy what the government rebuilt because it provides easier access to the terraces, he added.

Cultural landscape

The terraces were inscribed in the World Heritage List “in recognition of the organically evolved cultural landscape that has been shaped by sacred traditions and the ingenuity of the Ifugao people,” according to the 2008 book, “Impact: Sustainable Tourism and the Preservation of the World Heritage Site of the Ifugao Rice Terraces.”

Enshrined were the terraces in the villages of Batad and Bangaan in Banaue; those in the villages of Hapao, Dakkita, Maggok and Bakung in Hungduan town; those in the villages of Nagacadan and Julungan in Kiangan; and those in Mayoyao.

These were soon included in the list of endangered heritage sites in 2001, however, when government resources for their upkeep were reduced, Bahatan said.

According to the book, damage left by “uncontrolled tourism” and abandonment of the terraces were also reasons for their inclusion in the endangered list.

The terraces were removed from that list in 2012, following government assurance that it would have the relics repaired.

But De Lima said the government’s history of work on the terraces had not always been helpful. A report from the Ifugao provincial capitol revealed that government researchers first addressed the dwindling productivity of the rice terraces in the 1970s by developing specialty rice varieties, which farmers refused to plant.

Farmers were again encouraged to try hybrid rice in the 1990s when scientists continued to design rice strains for the terraces.

The government also failed to convince them to plant other crops, like vegetables, and to raise livestock in order to earn more from their farms, the report said.

“The first government intervention to sustain the rice terraces [during the 1970s] ended up disturbing the integrity of their cultural heritage, by introducing new plant and animal life into the ecosystem and by constructing facilities there to study the science that kept the rice terraces active,” De Lima said.

‘Introduce and reject’

He said it became a cycle that he described as “introduce and reject,” which is why the Aquino administration has resolved to imbibe the culture and the indigenous rice that is planted only once a year that have kept the terraces operating for centuries.

“This government will not force Ifugao farmers to employ a two-cropping system just to increase the yield … . The intention had always been good. We want to help improve the farms and improve the people’s livelihood. But [previous administrations] approached the rice terraces without considering the cultural dynamic that defined the terraces for 2,000 years,” he said.

“We need a cultural blueprint for reviving the terraces,” he said. This, he pointed out, would require a rethinking of tourism.

“Tourism is a viable economy for the Cordillera, but who benefits from this? Do communities earn from tourism? Tourists just come and watch people here perform for them, which they applaud and then they leave,” he said.

“How do we make tourism pay for the upkeep of the terraces?” De Lima asked.

According to the National Statistical Coordination Board, Ifugao hosted 93,037 foreign tourists in 2006. The arrivals peaked to 110,660 in 2008 but dwindled to 87,401 in 2011.

Expensive for tourists

Many villagers price food items a little higher for tourists, saying bringing products like soda and biscuits down to the terraces through porters will always be expensive. One delivery alone takes two hours of trekking.

De Lima said money would always be needed to pay for the restored terraces that remained idle because their owners had not returned to farm.

Many villagers have found more lucrative work as tourist guides, inn keepers and performers. Some of the abandoned farms are not making money, so families leave and find other employment outside Ifugao, people in Batad said.

Bahatan said the restored terraces would survive the elements for as long as these remain irrigated, but the terraces would again erode within five years if left unattended.

Keep subsidy flowing

Ifugao Rep. Teodoro Baguilat Jr. said his solution was to keep subsidy flowing to the terraces. “I plan to refile my bill creating an Ifugao Terraces Authority to serve as fund conduit to sustain state efforts in terrace conservation,” he said.

“Batad is just one cluster of terraces that needs repair…. But the actual maintenance—the daily grind that requires people to plow, plant and harvest rice from the terraces and to continuously repair the stonewalls and help irrigate the terraces—is the community’s decision,” he said.

“No amount of state funding can replace community work,” he said.