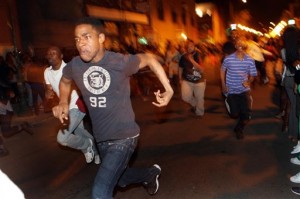

FLASH MOBS. Thanks to websites like Twitter and Facebook, more and more so-called flash mobs are materializing across the globe, leaving police scrambling to keep tabs on the spontaneous assemblies. The riots in London raise questions about whether conditions in the United States are ripe for a similar outburst. (AP Photo)

A black man killed by police. Mobs of looters. Cities charred and shaken. The riots in London mirror some of the worst uprisings in modern U.S. history.

And there are more parallels: Stubborn poverty and high unemployment, services slashed due to recessionary budget cuts, a breakdown of social values, social media that bring people together for good or bad at the speed of the Internet. And finally, there are a handful of actual attacks, isolated and hard to explain, by bands of youths in U.S. cities.

As Americans look across the Atlantic, a natural question arises: Could the flames and violence that erupted in Britain scar this country, too?

Police, elected officials, activists and regular citizens offer varied answers, reflecting the unsettled mix of race, class, lawlessness, and the chasm between haves and have-nots that may lie behind the unrest.

“History shows that the social tinder for such eruptions of massive violence and looting is usually widespread poverty without hope, and the spark is typically an incident of police brutality in the absence of a culture of police accountability,” said Benjamin Todd Jealous, CEO of the NAACP. “Such conditions exist in almost every major American city.”

Others, like British Prime Minister David Cameron, blame “criminality, pure and simple.” That echoes descriptions of some recent episodes of mob behavior in places like Philadelphia, Milwaukee, Chicago and Ohio. Stores have been pillaged, passers-by robbed, and random victims brutally attacked by dozens or occasionally hundreds of youths summoned through tools like Facebook and Twitter.

Philadelphia has responded by tightening youth curfews, and the Cleveland City Council passed a bill (later vetoed by the mayor) making it illegal to use social media to organize a violent mob.

Racial friction is an uncertain element. In Britain, TV images have shown mixed-race crowds creating mayhem. In recent mob violence in Philadelphia and Milwaukee, attackers were black and victims white.

The recent violence raises frightening memories of past racial unrest — the police club fracturing black civil rights marcher John Lewis’ skull in 1965 Alabama, or the cinderblock smashing white truck driver Reginald Denny’s head in 1992 Los Angeles.

Even though it’s unclear how much race motivates today’s mob violence, many see it as one of a combination of factors, which together make the grip of American law and order feel less secure.

“What we’re seeing on the streets in Britain right now is something we may be starting to see here,” columnist Peggy Noonan wrote in Friday’s Wall Street Journal.

“The cause was not injustice … (it was) greed, selfishness, a respect and even lust for violence, and a lack of moral grounding,” she wrote.

In Milwaukee, where there have been two cases since July of large group attacks, Bob Donovan, an alderman, said a “terrible disrespect for the police” has convinced him that what happened in London could definitely take place in America.

“If one person goes out on a rampage and is apprehended, they’re going to be held accountable,” he said. But when you have 100 or 200 or 400, the likelihood of holding everyone accountable just isn’t there.”

But Michael Coard, a black lawyer and self-proclaimed “agitator” in Philadelphia, sees no possibility of rioting there, despite the crimes that prompted the new curfew.

“In the United States, and certainly in Philadelphia, there is a buffer. We have a lot of black police officers, a black police commissioner, black city council members, a black mayor, and ultimately a black president,” Coard said.

“And it’s a buffer that might be open to solving the problem,” he continued. “I don’t have to burn this building down, I can go and talk to the mayor … When our parents and grandparents fought for black political representation, this is essentially what they were fighting for.”

Philadelphia also has a black district attorney, Seth Williams. He said that unlike the youths in London, many who engage in mob violence in the City of Brotherly Love simply think it’s fun to hurt people. He is prosecuting those who have been caught.

In the 20 years since Los Angeles tore itself apart after four white police officers were acquitted in the videotaped beating of black motorist Rodney King, the city has elected mayors who are Latino and black, and the police force has been overhauled.

Los Angeles police Capt. Jon Peters said he’s not overly concerned about riots, “knowing how well this organization is prepared to deal with any sort of crowd situation.” He noted that crime has not increased since the recession.

Jervey Tervalon, a writer who grew up in Los Angeles and edited the anthology “Geography of Rage: Remembering the Los Angeles Riots of 1992,” has seen change in the police, too.

Leading up to the riots, there was so much racial tension “you could see it coming. It was a powder keg.” Today, “I don’t think we’re going to have another riot, because I see much more understanding, more interaction with other cultures.”

The tension Tervalon senses today comes from people who can’t find work or support their families.

“I feel that rage,” he said. “We just endured this huge recession, but the oligarchs came out looking pretty. And then we have to cut Medicare and Social Security and leave us with no safety net?”

Marc Morial, CEO of the National Urban League, says budget cuts that lead to less jobs for young people could create problems: “I’m not prepared to say riots could happen here, but we need to pay close attention. To counteract negativity in young people, you have to create positive things.”