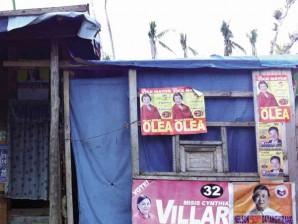

CAMPAIGN materials amid misery in the town of Baganga, Davao Oriental, which was hit hard by Typhoon “Pablo”. NICO ALCONABA

Romeo, 69, has already accepted the fact that his house and coconut farm were destroyed by Typhoon “Pablo.” Besides, he admits, almost everyone in his neighborhood in the village of Bobonao suffered the same fate.

He has rebuilt his house, using donated tents and wood salvaged from the debris as temporary walls. The 4-hectare coconut farm, however, is beyond saving.

“The trees that remain standing are already considered damaged. They (trees) are dying,” Romeo said.

His wife, 64-year-old Roselyn, said they have survived on relief goods provided by the government.

“But the relief goods have stopped coming,” she said.

“Where will we ask for help?” she said.

The answer could be just outside the couple’s dilapidated house—posters of candidates running for various posts in the elections next month.

“We just woke up with the posters already there,” Roselyn said.

The couple just smiled when asked if they were voting for the candidates on the posters.

“We still have not decided,” Romeo said.

They may have not decided on particular candidates, but the husband and wife said they would choose someone new.

“Bag-o na,” Romeo said.

His wife agreed. “We learned a lot from Pablo. We learned who among the candidates would be there to help us,” she said.

There are four mayoral candidates in this town—Roy Nazareno, son of outgoing three-term Mayor Remegio Nazareno; Ronnie Osnan, an independent candidate; Cecilio Monday, another independent candidate; and his cousin, incumbent Vice Mayor Arturo Monday. Of the four, Arturo Monday is considered the “tang-an,” or oldie, and is supported by reelectionist and unopposed Gov. Corazon Malanyaon.

The animosity between the mayor and his vice mayor became clearer when, days after the Dec. 4 typhoon, Malanyaon opted to channel relief goods through Vice Mayor Monday, instead of the local chief executive—Nazareno.

Malanyaon said she did so because Mayor Nazareno, who had been ill for months, was nowhere to be found.

In an earlier interview, however, Mayor Nazareno said he was just at the badly damaged municipal hall.

“Besides, if they really wanted to see me, they knew where I live,” the mayor said during the interview in his home, just beside the municipal hall grounds.

Malanyaon later decided to tap the military to lead relief and rehabilitation work. Mayor Nazareno, on the other hand, separately distributed goods donated by other local governments and private groups.

“The city governments of Davao and Panabo sent us relief goods, but we received nothing from the provincial government,” Mayor Nazareno said.

The situation has made residents think that the provincial government had abandoned them, with Malanyaon favoring her hometown Cateel, which was also devastated by the typhoon. The governor, again, denied this, saying relief goods were also given to Baganga town.

Still, many survivors in this town claimed that the relief goods they received came from private organizations that opted to go directly to the people than fall victim to politics.

To avoid accusations of being partisan, Fr. Darwey Clark, of Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish in the village of Lambajon, had to convert his damaged church into a mini-warehouse for relief goods.

Clark also took the initiative to ask private groups to conduct medical missions to attend to survivors who are sick. The Catholic Relief Services has helped Clark build new homes for some Lamjabon residents, Catholic or not.

“We don’t want to be involved in intrigues,” Clark told the Inquirer.

And intrigues are aplenty in this town.

Mayor Nazareno’s camp has accused its rival, Vice Mayor Monday, of distributing rice and GI sheets, which were allegedly kept from the public, during campaign rallies.

Malanyaon denied the distribution of relief goods during local campaign rallies. But some residents claimed the allegations are true.

“This (distribution) only confirms what we have long suspected—that they were keeping the rice and have these distributed during election time,” said a resident who asked not to be identified.

On Tuesday, hundreds of protesters staged a rally in the capital city of Mati, denouncing the provincial government for allegedly hoarding the relief goods. The protesters were led by Barug Katawhan, the same group that initiated the barricade at the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) regional office in Davao City in February and at the national highway in Montevista, Compostela Valley, in January.

But unlike the DSWD and Montevista highway barricades, there was no confrontation or dialogue in the Mati City rally. Malanyaon was in Davao City for a series of meetings. The road leading to the hilltop provincial capitol had been blocked by policemen and soldiers.

The protesters’ rally ended after three hours of speeches under the scorching heat of the sun on Paylon Street.

For those in the typhoon-hit towns, however, the “real fight” would be on election day.

Mark Anthony Julian, who will be voting for the first time, said he has already decided whom to vote for on May 13.

“Someone new,” the 18-year-old Julian said.

Julian, a student at Davao Oriental State College of Science and Technology, now works as an attendant in a bakeshop. Their house was damaged by the typhoon. His father, a farmer, lost his job as there are no more coconut trees in their village in Lucod.

“I have seen how government reacted after the typhoon—that’s enough basis for me to decide whom to vote for,” he said.