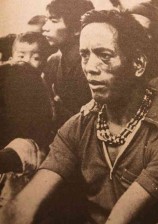

BAGUIO CITY—Every April 24 since 1985, Cordillerans mark People’s Day to honor Macliing Dulag, a pangat (village elder) of Barangay (village) Bugnay in Tinglayan, Kalinga.

He was murdered by government soldiers on that day 33 years ago for leading the struggle against the World Bank-funded Chico Dam project under the Marcos regime in the late 1970s.

Today, Macliing’s grave is a playground for children, a resting place for village dogs on a warm afternoon, or a meeting place for Butbut teens for their evening chats.

Many of the children who play on the grave do not know who Macliing was. However, the Butbut people who have gone to universities value the contribution of Macliing. They say the story of Macliing is taught in history books but is hardly mentioned in the village context.

Their elders deeply remember Macliing well.

Macliing was gunned down on the night of April 24, 1980, when soldiers of the Army’s 4th Infantry Division under Lt. Leodegario Adalem fired at the houses of Macliing and Pedro Dungoc, his neighbor and another opponent of the dam project.

The hydroelectric project was planned to inundate the sacred lands of the indigenous peoples near the Chico River—from south of Bontoc in Mt. Province to north of Tomiangan in Kalinga—to provide electricity to the lowlands.

Macliing died instantly while Dungoc was wounded. His death strengthened the unity of the Cordillerans against the dam project that was eventually scuttled by the government.

The soldiers did not enter Macliing’s house, but one of them persistently struck the door. Macliing asked his wife, Samun, to hold on to the door while he locked it.

The soldiers saw Macliing’s feet through the slit and sprayed the door with bullets. Macliing was shot in the left side of the chest and right pelvis, and died.

Buried without finery

Macliing was buried without the finery of a pangat. His daughter Manay recalled how her father was buried with the same blood-stained clothes that he wore when he was killed.

The women wept and cursed the people who killed Macliing. Apo Takhay, one of the oldest women in the village, said Macliing’s body was wrapped in a rattan mat with a knife tucked in his mouth, and laid out on his back.

He was not buried in the customary sangachil (death chair). Being laid on his back is a burial practice so Macliing’s spirit can avenge his death.

Door as reminder

Francis (Loc-an), eldest son of Macliing, recalled that he did not remove the door until 2006, as a reminder of the death of his father.

The door and the old house of Macliing still stand on the same place in the village. The house is now owned by the Panoy family who bought the property from Macliing’s children in 2005.

While on an anthropological fieldwork in southern Kalinga for 16 months in 2009, specifically among the Butbut people of Tinglayan, I lived in a house behind the old Macliing residence where his grave is also found in Barangay Bugnay.

Bullet holes

Because of my curiosity, Sammy Panoy and his wife, Bernadette, showed me traces of the bullet holes that hit the concrete wall inside Macliing’s house on the night of April 24.

The bullet holes measure about 2 x 3 inches while several holes are smaller ones from an automatic rifle and an M-16 rifle, based on the recovered empty shells outside of Macliing’s house.

The door where Macliing was killed is still in its original location, but the other old doors had been renovated and replaced with galvanized sheets.

Used as firewood

In early 2011, at the conclusion of my fieldwork, Bernadette handed me part of the lawanit door riddled with 13 bullet holes. Portions of the door had been used as firewood, and what was left was the door’s wood panel, which the couple gave as an atod (gift).

The Panoys recognized the significance of the door to local history and emergent national consciousness. “The children are about to use this as firewood. The rest are gone and you might be interested to keep it,” the couple told me.

I carried this part of the door panel back to Baguio City and had it chemically treated. With a double-sided glass, this is now at the University of the Philippines Baguio main library.

Fading epitaph

A few meters from the old Macliing house was the grave where the Butbut leader was buried. The concrete grave used to have paragraph-long epitaph inscribed in bold letters on a flat white marble stone.

The epitaph was written in Ilocano commemorating the death of Macliing. It was even memorized by Mario Dulag, the eldest grandson of Macliing, and Julie Dungoc, eldest daughter of Dungoc, who were both children when the tragic event happened.

Now in their mid-30s, both Mario and Julie could no longer remember the phrases inscribed on the grave.

The epitaph has been slowly erased through the years and only faint letters can be seen today.

The Panoy family plans to transfer the grave to a more convenient place, a few meters from its original location. But due to financial constraints, the family and the community are unable to do this and even make improvements on the Macliing memorial.

Historical landmark

Bugnay villagers do not remember any visit by people from relevant offices or efforts to declare the Macliing memorial a historical landmark if only for its importance in Cordillera and national history.

There were a handful of tourists who would look at the grave briefly and leave soon after. As such, we remember Macliing in many celebrations, but not the memorial where he was buried.

(Analyn “Ikin” Salvador-Amores is assistant professor of social anthropology at the University of the Philippines Baguio. She holds a master’s degree and a doctorate in social and cultural anthropology at Hertford College, Oxford University in England.)