Start ‘visita’ in Betis, Pampanga

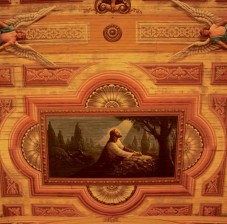

LIKENED TO SISTINE CHAPEL With religious paintings on its ceiling, Santiago de Apostol

Parish Church in Betis, Pampanga, has been likened by visitors to the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.Made of hardwood, Betis Church has survived lahar and floods. E.I. REYMOND T. OREJAS/INQUIRER CENTRAL LUZON

GUAGUA, Pampanga—Visual catechism—biblical teachings told through paintings and sculptures—is so rich at Santiago de Apostol (St. James the Apostle) Parish in the old district of Betis here that it has become a regular destination for pilgrims completing their Visita Iglesia on Maundy Thursday.

Because most spaces in the crucifix-shaped, four-century-old structure are devoted to ecclesiastical art, Archbishop Paciano Aniceto says visitors have likened it to the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, famous for its architecture and its decoration, notably the ceiling painted by Michelangelo between 1508 and 1512.

In refined Baroque style, Betis Church is 50 meters long, 12 meters wide and 10 meters high. Its flooring is made of hardwood that has survived lahar and floods.

It isn’t only a church that “continues to speak to its guests” through the many images, said Pampanga Auxiliary Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, a native of Betis, it is also steeped in local Church history.

The spread of the Catholic faith in Luzon began here. It is one of the first two “visitas” (chapels) established in 1572 by the Augustinians in Pampanga, the order’s first and last territory in the Philippines.

Article continues after this advertisementThe other chapel is St. Augustine Church in nearby Lubao town, according to the coffee-table book “Suli: Legacies of Santiago Apostol Church of Betis,” written by Nina Tomen and David.

Article continues after this advertisementThe book, published by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and St. James the Apostle Heritage Foundation Inc. in 2012, is regarded as the pioneer literature on Betis.

The National Museum declared the church a national cultural treasure in 2001.

The church’s parish priest, Fr. Emil Dizon, said it was best to start in Betis the Visita Iglesia—a tour of seven churches that pilgrims undertake after the commemoration of the Last Supper.

“The images invite you to reflect on God’s love,” Dizon said.

The image of St. James here holds a scallop, a symbol associated with the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, said Tomen.

Stairway to heaven

A visitor’s journey begins at the original wooden main door, which is now clapped tight to a modern door that was carved with figures representing Jacob’s dream of a stairway to heaven. The late sculptor Juan Flores, a native of Betis, installed this 20th-century addition.

The centerpiece of the church is a retablo, an assembly of wooden statues of St. James, the first apostle to be martyred, St. Augustine and the Augustinian saints.

There are images of Peter and Paul, the two pillars of the Christian faith. At the topmost niche looms the image of God the Father, portrayed as an old man. Below it is an image of Mary.

This retablo, according to the National Museum, is the “most beautiful” in Central Luzon.

Around here, St. James is called “Apung Tiago.”

The ceiling a little past the main door shows a painting of Jesus knocking at a door, as told in Revelation 3:20.

On the left sidewall below the choir loft is another painting of Jesus talking to a woman by the well. David said a

19th-century priest, Fr. Manuel Camañes, “may have offered it as an appropriate metaphor for what the church was meant to be—drawing from the wellsprings of life.”

The baptismal theme is taken on further by a painting at the baptistry below the belfry. It shows John drawing water from Jordan and baptizing Jesus.

Majestic portrayal

“As one enters the nave of the church and looks up at the ceiling, one gets awed by a majestic portrayal of the second coming of Christ. It has always been called a portrayal of the last judgment, but there is no scary portrayal here of separation of sheep on the right and goats on the left as in Matthew Chapter 25. What one sees, rather, is the enthronement of Jesus as the Son of Man (Daniel 7:13) with ‘nations and peoples of every language coming to him,’” the bishop explained.

Matthew, Mark, Luke and John—all Gospel writers—are painted on the corners of the pillars supporting the cupola of the church.

There is another painting of Jesus in Gethsemane before his passion and death. The images of Moses and Elijah, prophets in the Old Testament, are on the sides of this Agony in Garden scene.

David found a “compendium of salvation history” at the ceiling of the cupola. These are the fall of Adam and Eve and their expulsion from Eden (Genesis 3); hell and the monstrous beasts Leviathan and Behemoth (Isaiah 27:1 and 4 Ezra Chapter 6) and souls in purgatory; the battle of angels and the fall of Satan (Revelations Chapter 20).

The painting of the Last Supper in Betis is unique because in place of Judas is Paul, indicating that the early missionaries saw him as the “original advocate in favor of the mission to the Gentiles,” David noted.

The bishop said the paintings stirred his imagination since he was 3 years old.

“They attracted me to come to the church regularly for daily visits after school. They made me really curious about Jesus, his life and mission. Later when I entered the seminary and started reading the Bible, I was of course pleasantly surprised to discover that most paintings on the walls and ceilings of the Betis Church are in the Bible. I think God spoke to me,” he said.

Work of local artists

The three bells on the belfry are silenced from Maundy Thursday to Black Saturday to discourage gaiety, Tomen said. What Church leaders rang are the matraca—two wooden planks held fast by metal.

Around the church are Camañes’ artesian well, said to be one of the first in the country; the Glorietta built in 1931; the sculptures of the Holy Family and Sacred Heart, circa 1928; and the remnants of tableau pieces depicting the agony of Jesus Christ.

Tomen said records showed that Fr. Jose de la Cruz led the construction of Betis Church from 1660 to 1770. Construction took time as the population had little labor force. However, Tomen said the identity of the original creator of the visual catechism had not been established.

“It is widely believed that the murals, paintings and the trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) were executed by local artists working under the direction of a priest, for the artworks represent more than just basic catechism,” she said.

Church records showed that paintings and other artworks had been in the church as early as 1790.

Among those who helped restore the paintings were the father-and-son tandem of Jose and Macario Ligon under the direction of Fr. Santiago Blanco, OSA, the last Augustinian missionary to manage the parish from 1939 to 1949. Mariano Henson repainted the works twice in 1890 and 1895.