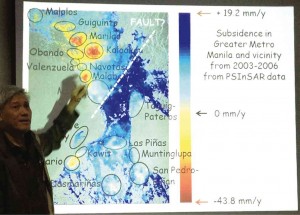

SIGNS Architect Paulo Alcazaren points out areas (encircled) in and around Metro Manila where subsidence had been mapped and the line where a possible fault line has developed, during a media presentation in San Juan on Wednesday. He is part of a coalition that warns that Manila Bay reclamation projects are vulnerable to earthquakes. NATHANIEL MELICAN

The Department of Science and Technology (DOST) has started studying a renowned geologist’s initial findings which hint at the formation of a new fault line that cuts through Quezon City and intersects with the Marikina Valley Fault Line.

According to Dr. Kelvin Rodolfo whose findings prompted the DOST to conduct the follow-up study, a team led by geological expert Dr. Mahar Lagmay was verifying his theory.

At a press conference the other day called by the Save our Seas-Manila Bay group which is opposed to a proposed reclamation project on the bay, Rodolfo said he stumbled upon what initially appeared to be a new fault line while observing land subsidence patterns due to ground water extraction in Metro Manila between 2003 and 2006.

“We used a very high-tech satellite tool called Permanent Scatter Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar. In short, the satellite takes images of the earth over time and combines it to show subsidence through various colors,” he added.

The images collected of Metro Manila and neighboring provinces showed yellow to red patches in the towns of Guiguinto, Malolos, Marilao and Obando in Bulacan; Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, Valenzuela, Manila, parts of Quezon City, Taguig, Pateros, Las Piñas, Muntinlupa; and portions of the provinces of Cavite and Laguna.

43.8 mm per year

This, Rodolfo said, meant that the land was sinking, primarily because of too much groundwater extraction. It must be recalled that some areas in Camanava (Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas and Valenzuela) sank at the rate of 43.8 millimeters per year between 2003 and 2006.

However, a noticeable part of the map, south of where the heaviest subsidence was observed, was in dark blue and this meant that the area was rising at around 19.2 millimeters per year during the same period.

“You notice that on one side, there seems to be small increases, meaning tectonics is raising the ground but groundwater pumping is counteracting it. But in areas south of the line, it’s definitely going up. What it’s saying is we likely have a new fault which we just found in this study of land subsidence,” Rodolfo said.

However, he cautioned that much more work needs to be done before it can be confirmed as a fault.

“These pictures from the satellite are only half of the story. It’s only good when it can be verified through studies conducted on the ground,” he said.

“[Dr.] Mahar Lagmay and his staff are doing a study which is still ongoing and funded by the DOST,” he added.

Lagmay is the head of the DOST’s multibillion-peso Project Noah (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards), a two-year flood forecasting and warning system. A University of the Philippines (UP) professor, he earned his doctorate in Earth Sciences from the University of Cambridge.

Rodolfo, on the other hand, is a professor emeritus of the University of Illinois, Chicago and an adjunct professor of the UP National Institute of Geological Sciences. He earned his doctorate in geological sciences at the University of Southern California. He is also a consultant of Project Noah.

When contacted by the Inquirer for comment, the director of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) said that there was not enough evidence for now to support Rodolfo’s theory.

No proof for now, says Phivolcs

“We [saw] the same thing they [did] but we did not interpret it the same way. We didn’t find any evidence of a new fault,” Renato Solidum said.

According to him, a very careful evaluation of data was required for any such conclusions to be made. Solidum noted that the presence of the West Valley Fault was “very obvious” to seismologists unlike the supposed new fault.

In determining if there really was a new fault in Metro Manila, he said the next question to ask would be if this fault was active, and if active, whether it could cause a major earthquake.

Metro Manila, Solidum noted, was both a plateau and a delta, the former being a buildup of sturdy rocks, and the latter referring to a place where sand is deposited.

“This means there’s soft ground and hard ground. So we have to be certain. We have to be able to explain if the ground is subsiding or uplifting,” he said.

“If indeed there’s a major fault, it must be associated with a major earthquake. Some people are confused if you say there is a fault because you have to ask, ‘Is it active?’” Solidum added.

He said that Phivolcs scientists had also observed subsidence in a “central part of Metro Manila” applying the same technology Rodolfo used but they did not make the same inferences.

A 2000 seismic hazard assessment of Metro Manila published in the Bulletin of Seismological Society of America showed that Metro Manila had been “heavily damaged by earthquakes at least six times in the past 400 years, but the specific sources for the earthquakes are uncertain.”

Scientists believe the MarikinaValley Fault System, or the Valley Fault System that runs north to south along the west and east edges of the Marikina Valley, is the likely source. It has two segments, the East Valley Fault and the West Valley Fault.

There are fears that the West Valley Fault could make a major movement at any time. A risk assessment study funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency noted that the West Valley Fault had moved four times and generated strong earthquakes within the last 1,400 years.