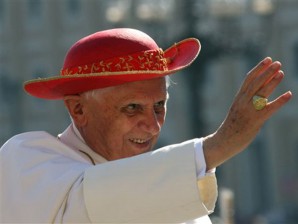

FILE – This Sept. 6, 2006 file photo shows Pope Benedict XVI wearing a “saturno hat”, inspired by the ringed planet Saturn, to shield himself from the sun as he waves to the crowd of faithful prior to his weekly general audience in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican. (AP Photo/Pier Paolo Cito, files)

VATICAN CITY — On Monday, April 4, 2005, a priest walked up to the Renaissance palazzo housing the Vatican’s doctrine department and asked the doorman to call the official in charge: It was the first day of business after Pope John Paul II had died, and the cleric wanted to get back to work.

The office’s No. 2, Archbishop Angelo Amato, answered the phone and was stunned. This was no ordinary priest. It was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, his boss, who under the Vatican’s arcane rules had technically lost his job when John Paul died.

“It tells me of the great humility of the man, the great sense of duty, but also the great awareness that we are here to do a job,” said Bishop Charles Scicluna, who worked with Ratzinger before he became Pope Benedict XVI, inside the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

In resigning, Scicluna said, Benedict is showing the same sense of humility, duty and service as he did after the Catholic Church lost its last pope.

“He has done his job.”

When Benedict flies off into retirement by helicopter on Thursday, he will leave behind a church in crisis — one beset by sex scandal, internal divisions and dwindling numbers.

But the 85-year-old pope can count on a solid legacy: While his very resignation was his most significant act, Benedict — in a quieter way — also set the church back on a conservative, tradition-minded path.

He was guided by the firm conviction that many of the ills afflicting the church could be traced to a misreading of the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

He insisted that the 1962-65 meetings that brought the church into the modern era were not a radical break from the past, as portrayed by many liberals, but rather a continuation of the best traditions of the 2,000-year-old church.

Benedict was the teacher pope, a theology professor who turned his Wednesday general audiences into master classes about the Catholic faith and the history, saints and sinners that contributed to it.

In his teachings, he sought to boil Christianity down to its essential core. He didn’t produce volumes of encyclicals like his predecessor, just three: on charity, hope and love. (He penned a fourth, on faith, but retired before finishing it.)

Considered by many to be the greatest living theologian, he authored more than 65 books, stretching from the classic “Introduction to Christianity” in 1968 to the final installment of his triptych on “Jesus of Nazareth” last year — considered by some to be his most important contribution to the church. In between he produced the “Catechism of the Catholic Church” — essentially a how-to guide to being a Catholic.

Benedict spent the bulk of his early career in the classroom, as a student and then professor of dogma and fundamental theology at universities in Bonn, Muenster, Tuebingen and Regensburg, Germany.

“His classrooms were crowded,” recalled the Rev. Joseph Fessio, a theology student of Ratzinger’s at the University of Regensburg from 1972-74, and now the English-language publisher of his books.

“I don’t recall him having notes,” Fessio said. “He would stand at the front of the class, and he wasn’t looking at you, not with eye contact, but he was looking over you, almost meditating.”

It’s a style that he’s kept for 40 years.

“If you hear him give a sermon, he’s speaking not from notes, but you can write it down and print it,” Fessio said. “Every comma is there. Every pause.”

Benedict never wanted to be pope and he didn’t take easily to the rigors of the job. Elected April 19, 2005, after one of the shortest conclaves in history, Benedict was, at 78, the oldest pope elected in 275 years and the first German in nearly a millennium.

At first he was stiff.

Giovanni Maria Vian, editor of the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano, recalled that in the early days Benedict used to greet crowds with an awkward victory gesture “as if he were an athlete.”

“At some point someone told him that wasn’t a very papal gesture,” Vian said. Benedict changed course, opting for an open-armed embrace or an almost effeminate twinkling of his fingers on an outstretched hand as a way of connecting with the crowd.

“No one is born a pope,” Vian said. “You have to learn to be a pope.”

And slowly Benedict learned.

Crowds accustomed to a quarter-century of superstar John Paul II, grew to embrace the soft-spoken, scholarly Benedict, who had an uncanny knack for being able to absorb different points of view and pull them together in a coherent whole.

He traveled, though less extensively than John Paul, and presided over Masses that were heavy on Latin, Gregorian chant and the silk brocaded vestments of his pre-Vatican II predecessors.

Benedict seemed genuinely surprised by the warm reception he received — as well as the harsh criticism when things went wrong, as they did when he lifted the excommunication of a bishop who turned out to be a Holocaust-denier.

For a theologian who for decades had worked toward reconciliation between Catholics and Jews, the outrage was fierce and painful.

Benedict was also burdened by what he called the “filth” of the church: the sins and crimes of its priests.

As prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Benedict saw first-hand the scope of sex abuse as early as the 1980s, when he tried unsuccessfully to persuade the Vatican legal department to let him remove abusive priests quickly.

But it was 2001 before he finally stepped in, ordering all abuse cases sent to his office for review.

“We used to discuss the cases on Fridays; he used to call it the Friday penance,” recalled Scicluna, who was Ratzinger’s sex crimes prosecutor from 2002-2012.

Still, to this day, Benedict hasn’t sanctioned a single bishop for covering up abuse.

“Unfortunately, Pope Benedict’s legacy in the abuse crisis is one of mistaken emphases, missed opportunities, and gestures at the margin, rather than changes at the center,” said Terrence McKiernan of BishopAccountability.org, an online resource of abuse documentation.

He praised Benedict for meeting with victims, and acknowledged the strides the Vatican made under his leadership. But, he said Benedict ignored the problem for too long, “prioritizing concerns about dissent over the massive evidence of abuse that was pouring into his office.”

“He acted as no other pope has done when pressed or forced, but his papacy has been reactive on this central issue,” McKiernan said in an email.

Benedict also gets poor grades from liberal Catholics, who felt abandoned by a pope who seemed to roll back the clock on the modernizing reforms of Vatican II and launched a crackdown on American nuns, deemed to have strayed too far from his doctrinal orthodoxy.

Some priests are now living in open rebellion with church teaching, calling for a rethink on everything from homosexuality to women’s ordination to priestly celibacy.

“As Roman Catholics worldwide prepare for the conclave, we are reminded that the current system remains an ‘old boys club’ and does not allow for women’s voices to participate in the decision of the next leader of our church,” said Erin Saiz Hanna, head of the Women’s Ordination Conference, a group that ordains women in defiance of church teaching.

The group plans to raise pink smoke during the conclave “as a prayerful reminder of the voices of the church that go unheard.”

But Benedict won’t be around at the Vatican to see it. His work is done. “Mission Accomplished,” Vian said.

And as the pope told 150,000 people in his final speech as pope: “To love the church is to have the courage to make difficult, painful choices, always keeping in mind the good of the church, not oneself.”