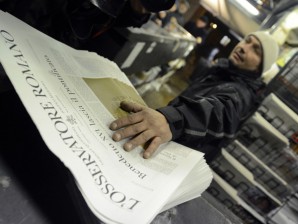

Picture taken on February 11, 2013 shows a newspapers seller displaying copies of the Vatican’s newspaper, the Osservatore Romano, with the frontpage dedicated to the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI at a newstand at the Vatican. AFP FILE PHOTO

VATICAN CITY— After a Pole and a German, will the Roman Catholic Church revert to an Italian leader once again?

Italy has the biggest voting bloc in the conclave to elect the next pope, with 28 of the 117 cardinal electors, but only one Italian, Milan Archbishop Angelo Scola, is widely seen as “papabile”, or a strong candidate to succeed Benedict XVI.

Many cardinals oppose the idea of adding to the long line of Italians who preceded the back-to-back foreign popes, John Paul II of Poland and the German Benedict.

The last pope before John Paul II who did not hail from the Italian peninsula was Adrian VI, from the bishopric of Utrecht who died in 1523.

The “Vatileaks” scandal has tarnished the reputation of the Italians in the Curia, as the Vatican government is known, by exposing intense power struggles among them.

On the other hand, the scandal underscored the need for urgent reforms, which could suggest the need for leadership by an insider who knows the ropes.

Although Scola is not an insider, his elevation from patriarch of Venice to run the Milan archdiocese – Europe’s biggest and one that has produced several past pontiffs – could be seen as a launchpad for the papacy.

Even before the pope’s shock resignation announcement on February 11, the square-jawed, no-nonsense Scola was mentioned as a favourite of Benedict’s and of sufficient intellectual stature to succeed him.

Highly cultivated and morally conservative, the 71-year-old son of a truck driver is in the same theological mould as Benedict, with a nuanced view of the Second Vatican Council reforms of the 1960s that insists on continuity with tradition.

Scola has since his youth been associated with a conservative movement, Communion and Liberation, which is highly influential in Italy.

He has been on the front lines of some of Benedict’s main battles, for example fighting rising secularism in Europe.

He slammed France in December as the parliament debated legislation to allow gay marriage which is fiercely opposed by the Church.

“The supposedly neutral state is far from it, adopting a specific culture, which through legislation becomes the dominant culture,” he said.

And in a bid to combat Islamophobia, Scola founded Oasis, a respected magazine of Islamo-Christian thought.

On the downside for Scola is his reputation for being somewhat dry and unapproachable — a bit isolated, and more conservative than his predecessors in Milan.

Two other Italians are seen as possibles: Gianfranco Ravasi, the Vatican’s culture secretary, and Mauro Piacenza, head of the powerful Congregation for the Clergy.

The media-friendly Ravasi is brimming with ideas and initiatives, open and friendly, as well as cerebral – capable of evoking an early Church father, Jean-Paul Sartre and a Hindu mystic in the same speech.

One of the first prelates to embrace Twitter, he teamed up with Benedict to create a series of encounters with non-believing intellectuals, the Court of the Gentiles.

Conservative in some ways and modern in others, Ravasi was selected to preside over Benedict’s last spiritual exercises for Lent this year.

On the first day of these meditations, the 70-year-old cardinal created a stir by citing a letter from the parents of a baby with a fatal illness that he had just received: “A cry of suffering that we would deem blasphemous on the surface is often heard more attentively by God than many prayers” at Sunday mass, he told the cardinals.

Benedict XVI appreciates such audacious thinking and warmly thanked Ravasi for his remarks, making a comment that could be prophetic: “The Lord will reward you for this work, which you have performed brilliantly.”

On the other hand Ravasi is seen as too intellectual and not sufficiently down to earth.

Piacenza, 68, is another Italian who enjoys the pope’s favour. He is rigorous, very conservative, with a reputation as the hardest worker in the Curia, but more often tipped to replace the Vatican number two Tarcisio Bertone than to become the next pope.

But if an Italian emerges from next month’s conclave as pope, it is likely not to be thanks to the “Italian bloc” of cardinals – as they are far from united.

There is a “tribal aspect among the Italians”, Vatican expert John Allen of the National Catholic Reporter told AFP.