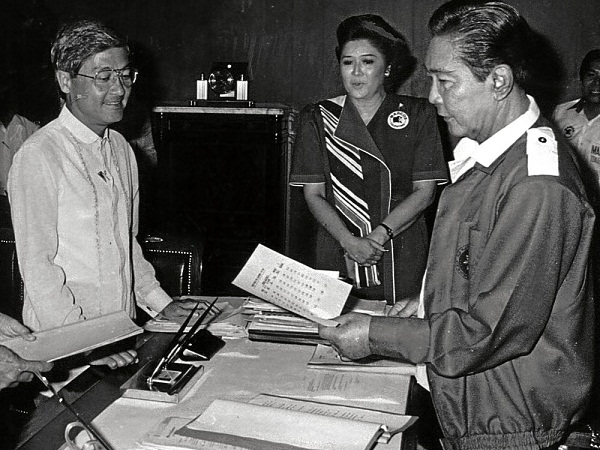

THE MARCOS YEARS Trade Secretary Roberto Ongpin confers with President Marcos and First Lady Imelda Marcos in the “snake pit” called Malacañang to which he was conscripted in 1979. INQUIRER PHOTO

(First of two parts)

When the phone rang one day in May 1979, he was not to know that he would be caught in one of the most tumultuous chapters in Philippine history.

“Do you know what time it is in London?” Roberto V. Ongpin said, the drowsiness evident in his voice. “It is 4 a.m.”

“Bobby, the President wants to talk to you,” said the voice at the other end, half a world away in Malacañang. It was Ruben Ancheta, an aide to President Ferdinand Marcos.

“Pare, please, give me two hours,” Ongpin said.

“All right. I will tell him,” Ancheta said.

Ongpin told the story of how he was conscripted by Marcos in an interview with the Inquirer at his penthouse office in the Alphaland Southgate Tower, a shopping mall and office complex which he owns, overlooking the western part of the capital and the spectacular Manila Bay farther on.

“You know, when the President calls [and] you are sleeping, you can no longer sleep,” said the 76-year-old business tycoon as he sat sipping his scotch and picking at a sandwich. He wore a cotton barong, his silver hair closely cropped.

After a while, the phone rang again. Ancheta put on the President.

“Sorry, I woke you up.”

“That’s okay, Mr. President.”

“When are you coming back?”

“Two weeks.”

“Can you come back in three days?”

Apparently, the President was planning to shake up his Cabinet, five years after he declared martial law, said Ongpin, at the time the chair and managing partner of SGV, the highly regarded Philippine auditing firm whose clients included some of the country’s—and the world’s—largest corporations.

“Mr. President, why am I being called?”

“Basta. Come back and we will talk.”

“At the time, it was very difficult to say no to him, you know,” Ongpin said with a laugh.

He returned forthwith to Manila and went to the Palace. The guard at the gate gave him a hard time and he had to wait. Finally at 2 p.m., he was let in. Marcos was in tip-top shape, looking very athletic. He had just come from the pelota court.

According to Ongpin, the Marcos he met that day was so far removed from the ailing man of three years later who was stricken with renal problems—a subject of much speculation in the nation where media facilities were controlled—and had to undergo two kidney transplants.

The first donor, Ongpin said, was Marcos’ namesake son who is now a senator. A rejection soon set in. He had another transplant several years later. The donor this time was a soldier in the presidential security group who was from his Batac hometown in Ilocos Norte. The organ kept him alive until he died in exile in Hawaii in 1989 at the age of 72.

Forceful guy

“I heard you are a forceful guy,” Marcos said to Ongpin.

“I don’t know if ‘forceful’ is the right word, Mr. President, but I do speak my mind. I don’t think I am the right man for your Cabinet. I think I will bring embarrassment to your Cabinet.”

“Why?”

“Mr. President, I have a very complicated personal private life. I don’t think you want me in your Cabinet.”

And then he told Marcos why.

At this point in the INQUIRER interview, Ongpin, who is married to a Filipina and has two children by her, asked that the tape recorder be switched off.

German beauty

But he could not resist showing a copy of a glossy magazine with his daughter on the cover. Her mother is German. She is a lovely woman worthy of a Miss Universe crown. She runs Ongpin’s world-class resort on the 400-hectare Balesin island that he owns on Lamon Bay in Quezon. He also has a son, whose mother is Australian. But Ongpin obviously was very proud of the German daughter. This gem of beauty and brains is evidently a source of joy for the man with an eye for beautiful women and an uncanny knack for making money.

The Forbes list of the top 40 wealthiest Filipinos ranked Ongpin 21st in 2010, with a net worth of $300 million. In 2011, he jumped to the ninth slot with a net worth of $1 billion, comprising holdings in several dozen companies ranging from gaming, communications, petroleum and mining.

“I want you to know that those things do not bother me,” Marcos told Ongpin.

“He wanted to know more about me, what I did, where I went to school,” recounted Ongpin, a certified public accountant educated at the Ateneo who also has an MBA from Harvard.

What was supposed to be a half-hour meeting lasted three hours.

“I would have thought that he would have done research on me, but he did not, or else he kind of just enjoyed talking to me. From the start, we hit it off, as if we were on the same wavelength. He knew that I speak my mind and I told him I might not stay long with him because I am a hothead, that he might get upset with me,” recalled Ongpin.

“No, no,” Marcos said. “I like that. I want people to speak up, because nobody has been speaking to me as they should.”

Luncheons with Marcos

He told the President: “If that’s the way you want it, we can have a deal. The minute that I feel I am not of help to you, you would let me go and the minute that you feel I am not of help to you, whatever, sorry na lang, you let me go, if possible gracefully, not fire me,” Ongpin recounted, laughing.

“Fair enough,” Marcos said.

And so he joined Malacañang, which Marcos’ daughter Imee once described as a “snake pit.”

Ongpin had a lot of meetings, almost every day, with Marcos before he was finally sworn in as minister of trade and industry in the Cabinet revamp announced during the President’s State of the Nation Address in July 1979.

Discussions even went on in the golf course. Ongpin said he was a fairly good golfer then, like the President, although he said Marcos had a “strange swing,” motioning with an imaginary club circling over his head like a helicopter blade before bringing it down to strike a ball.

He hated having lunch with the President, who always had a spartan diet of pinakbet—the Ilocano vegetable stew, mainly eggplant without pork—and plain rice. Starved, Ongpin would order hamburger. “I was always hungry.”

Run-ins with Imelda, Ver

Soon enough, Ongpin tangled with the President’s powerful wife, Imelda, and Gen. Fabian Ver, the Armed Forces chief of staff who also headed the presidential guards and the national intelligence service. Marcos, Imelda and Ver made up the triumvirate running the country.

“My first clash was with Imelda,” he said. The flamboyant first lady, her protégé Joly Benitez, and many hangers-on were badgering him with their “harebrained” ideas, he said. They complained to Marcos and Ongpin would explain to the President he could not go along with their proposals. At one time, he was called by Imelda to ask him why he was harassing Benitez. “Ma’am, I’m not bothering him,” he would tell her.

By that time, Imelda had organized the Ministry of Human Settlements. She was also governor of Metro Manila. The ministry was “basically functioning like a government within a government,” said Ongpin. It had offices similar to the departments of industry, agriculture, social welfare, science and technology.

“I said, ‘Ma’am, I’m doing a job. If you think I am doing something wrong, let me know. And if you want, please feel free to go to the President. I can go anytime. I didn’t ask for this job. I don’t need this job.’”

He said Imelda, “as was her wont,” also tried to put down the urbane Prime Minister Cesar Virata, who was also the finance minister, telling the President office gossip about Virata.

‘It’s nuts’

When she learned about Ongpin’s German daughter, Imelda ran to Marcos with the gossip. Marcos told her he already knew this. “She thought she had a bazooka,” said Ongpin, laughing.

Ongpin talked about an Imelda proposal to set up a semiconductor company, Asian Reliability, to be run supposedly by a Chilean expert. She wanted the Development Bank of the Philippines to sign a $30-million loan to the company. He questioned the project, “What’s our competitive advantage?”

“But we will learn,” Imelda insisted.

“One afternoon, the President calls me. Bobby, this Asian Reliability, I was told you don’t like it. I said, ‘Sir, it’s nuts, it’s crazy!’”

Danding Cojuangco’s friend

He said there were many more of these kinds of run-ins. His candidness characterized his dealings with the President. “I really did not want this job,” he said, but he stayed on, for seven years. He suspected that Virata, a former SGV colleague, had recommended him to Marcos. He never confirmed this.

“As we got to know each other, I got involved in so many things that I was not supposed to,” said Ongpin. “It was tough.”

He said he thought he served as a foil to all the shenanigans going on at the Palace and, as a result, made a lot of enemies, except for businessman Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco, Marcos’ ambassador at large and head of the state-owned United Coconut Planters Bank, depository of the multibillion-peso coconut levy funds.

“Danding and I have been friends. He was my client at SGV,” he said. When Cojuangco had projects, he would discuss them with Ongpin before the businessman made his presentations.

Loan from Brunei sultan

All hell broke loose after the opposition leader, former Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr., was assassinated on Aug. 21, 1983, on his return from three years of self-exile in the United States.

“Wow! In one day, $770 million in short-term loans were withdrawn. We were left with nothing. We were really about to collapse,” said Ongpin.

Ongpin was dispatched urgently to seek loans from the leaders of Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore.

Brunei’s Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah had long been a personal friend of Ongpin. “We used to do things together,” he said, reminiscing with a smile. He left on a 5:30 a.m. flight to Brunei’s capital for a meeting with the absolute monarch of the oil-rich country.

“We need a short-term loan,” he told the sultan. “Understood,” Bolkiah said, and gave him $150 million.

$75M from Mahathir

His next stop was Kuala Lumpur, whose prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, was likewise a soul mate of old. He got $75 million from the Malaysian leader who, after the fall of Marcos, even offered to send a plane and fly Ongpin out of Manila.

Ongpin proceeded to Singapore and saw the crusty Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. “Are you really the minister?” Lee asked. “I looked really young,” he said with a laugh. “I was 42.”

“I know what you want. You’ll never get a single cent from me,” said Lee.

“Well, in that case, sir, I will go.”

‘Catharsis’

Lee stopped him, saying he wanted to talk to him some more. It lasted four hours, during which Ongpin argued with the prime minister, telling him he was wrong when he needed to. And in a book that Lee recently wrote, Ongpin read that Lee mentioned the contentious Filipino trade minister.

Ongpin got nothing from Lee, except probably enriching his vocabulary. Lee told him that while watching the mammoth crowd that attended the funeral of Benigno Aquino, he thought the Philippines was undergoing a “catharsis.” When he got home, Ongpin looked up the word in the dictionary.

(Next: US conditions to save Marcos)

First posted 12:29 am | Sunday, February 24th, 2013