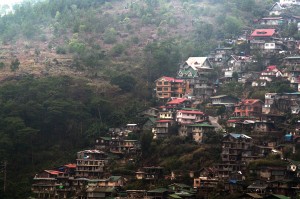

URBAN BLIGHT Houses and other structures rise on every available space at Quirino Hill in Baguio City. RICHARD BALONGLONG

Heated arguments are never in short supply whenever Baguio City residents discuss why squatting and overpopulation have ruined the summer capital.

A 2013 case study commissioned by the Baguio Country Club (BCC) devoted most of its pages to evidence that the current city population “is 13 times more” than what American architect Daniel Burnham envisioned when he designed Baguio for 25,000 people in the early 1900s.

It said the uncontrolled population growth, worsened by squatting and migration, has taxed the city’s capacity to supply water and other resources, and brought it precariously to the edge of urban decay.

The University of the Philippines also addressed the population issue. A paper by Maria Lorena Cleto, a UP graduate student in urban planning, observed that the number grew to 325,880 in 2010, and may reach 419,371 by 2020.

Cleto said the increase had outpaced the growth of the local economy—

notably by a steady rise in unemployment from 5.4 percent in 1990 to 17.2 percent in 2011.

These were the issues that fueled the 12-year-old task to amend the Baguio City Charter of 1909—from the time it was introduced as a campaign platform in 2001 by lawyer Pablito Sanidad to the moment House Bill No. 121 (the amended Baguio City Charter) passed Congress and reached the desk of President Aquino at the end of 2012.

Aquino vetoed the bill last week for equally contentious issues regarding property rights.

Solution to squatting

When it was introduced in 2001 as a measure by Sanidad’s opponent, then Baguio Rep. Mauricio Domogan, the draft amendments intended to make the city better equipped to manage its townsite reservation through updated laws and by altering how lands are sold.

The only city operating as a townsite today, Baguio lands are auctioned off to sales applicants by a committee composed of the environment secretary, the director of lands and the city mayor.

Domogan, who is now mayor, attributed the process’ vulnerability to graft for a backlog of 5,600 townsite sales applications (TSAs) over the past 30 years.

He said the TSA committee “never met for almost five years since the secretary of the DENR (Department of Environment and Natural Resources), who chairs the committee, was always unavailable for scheduled meetings to [process] the pending applications.”

The solution he and Baguio Representative Bernardo Vergara proposed in their respective charter measures, from the 12th Congress to the current 15th Congress, was to grant the mayor chairmanship of the committee to speed up the process.

But the charter change initiative quickly drew protests.

Squatter groups believed it was a class legislation because one of its proposals to grant the city the proprietary ownership of the townsite reservation gives the mayor power to eject them from the city.

City planning and development office records show that Baguio has 2,692 households considered squatters, many of which have settled within national reservations.

The BCC study says a census held before the 1963 elections recorded the presence of 1,959 squatter households who thrived due to “tolerance permits” and by Ordinance No. 386 of 1963, which legalized settlers who have tax declaration records as of Dec. 31, 1962.

Baguio residents belonging to indigenous groups believed the amended charter further disenfranchised their right over ancestral lands from which they were displaced by the American colonial government.

The DENR also weighed in because the original amendments appeared to give Baguio control over the disposition of townsite lands, a task which the 1987 Constitution grants only to the President or the environment secretary who acts on the President’s behalf.

In his January 21 veto letter to Speaker Feliciano Belmonte Jr., Aquino made the same case against the Baguio charter bill.

Flawed

He said the amended charter was “laudable” but inherently flawed because “it is unusual for the city charter to contain provisions for the alienable and disposable lands.”

Aquino said the bill could be misinterpreted to mean it empowers Baguio to dispose of lands, which “impinges on the DENR’s exclusive mandate over control of alienable and disposable lands and runs counter to the laws governing the disposition of townsite reservations.”

The President also took to task a provision in the amended charter that allows Baguio to keep the proceeds of townsite sales and miscellaneous land sales.

“Section 36 of the proposed measure states that the proceeds from the sale of lands through miscellaneous sales applications shall accrue to the city. Section 80 of the Public Land Act (Commonwealth Act No. 141) mandates that [townsite and miscellaneous sales] shall accrue to the national treasury… instead of the city treasury,” Mr. Aquino said.

Section 2544 of the 1909 Baguio City Charter, however, grants Baguio that privilege. It says that “all money from the sale of lands … accrue to the city,” particularly fees “received from the sale of public lands.”

Aquino said the amended charter also impacts on the Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA), which administers Camp John Hay. His letter points out that Republic Act No. 7227 (the BCDA law of 1992) grants it power to dispose of alienable and disposable lands within former American baselands and to keep the proceeds from the sale.

Other solutions to overpopulation have been set in motion. For example, the economic sharing arrangement called BLISTT (Baguio City and the neighboring Benguet towns of La Trinidad, Itogon, Sablan, Tuba and Tublay) is a long-term strategy to discourage migration once the economies of the city’s nearby communities improve.

The BCC lawyers, Abelardo Estrada and Cesar Oracion, also discussed the option of petitioning the Supreme Court for a writ of “kalikasan” against squatters who imperil the mountain resort’s environment.

Can Baguio charter advocates attempt a third charter measure?

Vergara is ambivalent. “The veto meant advocates of a Baguio charter that addresses the city’s land problems would need to start from scratch. I don’t know if I have the energy for a second bout,” he said.